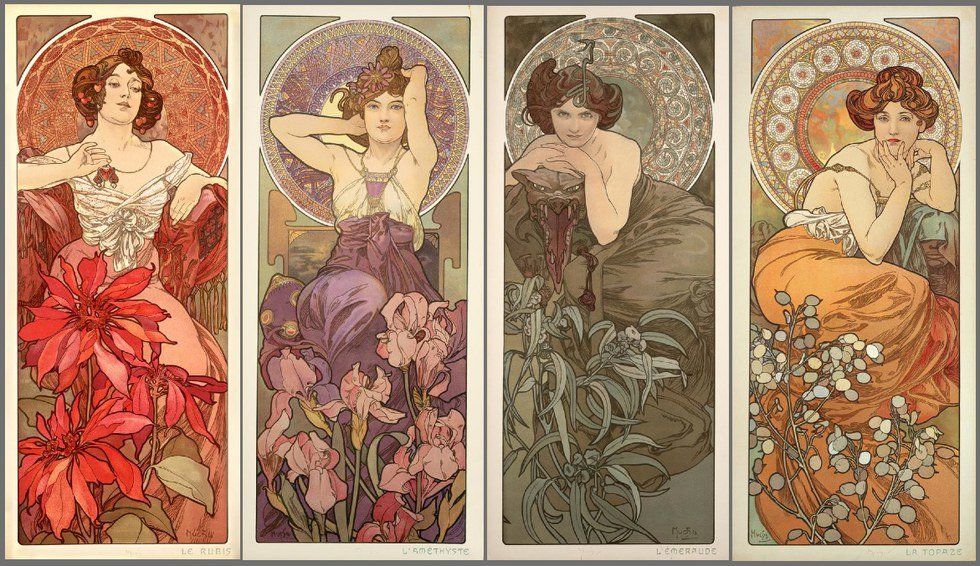

I have always been attracted to the crisp lines, decadent colors, and aura of antiquity behind art pieces like the one above. They contained a feel of the history-textbook olden days but with a composition and subject current to today. Where did this style come from? Was this a new illustration movement? The answer I discovered in my Art History class: no.

The beautiful figures and ornaments felt nostalgic because they are inspired from movement called Art Nouveau. It’s a fancy term used interchangeably with modern art and deco pieces today, but in the late 1800s, it was an important trend that brought art back to its true meaning.

"Wren's City Churches" (1883) by A.H (Arthur Heygate) Mackmurdo, 1851-1942

The Art Nouveau movement of the mid to late 19th century was both innovative towards the future and dedicated to the past. The craftsman returned to the world reborn as an artist after the Arts and Crafts movement migrated from the English islands to the European continent. A passion returned for nature and visual beauty, throwing away heavily used symbolism and encrypted messages of the past arts. Art Nouveau was sadly short lived, but made an important statement — that art could simply be art.

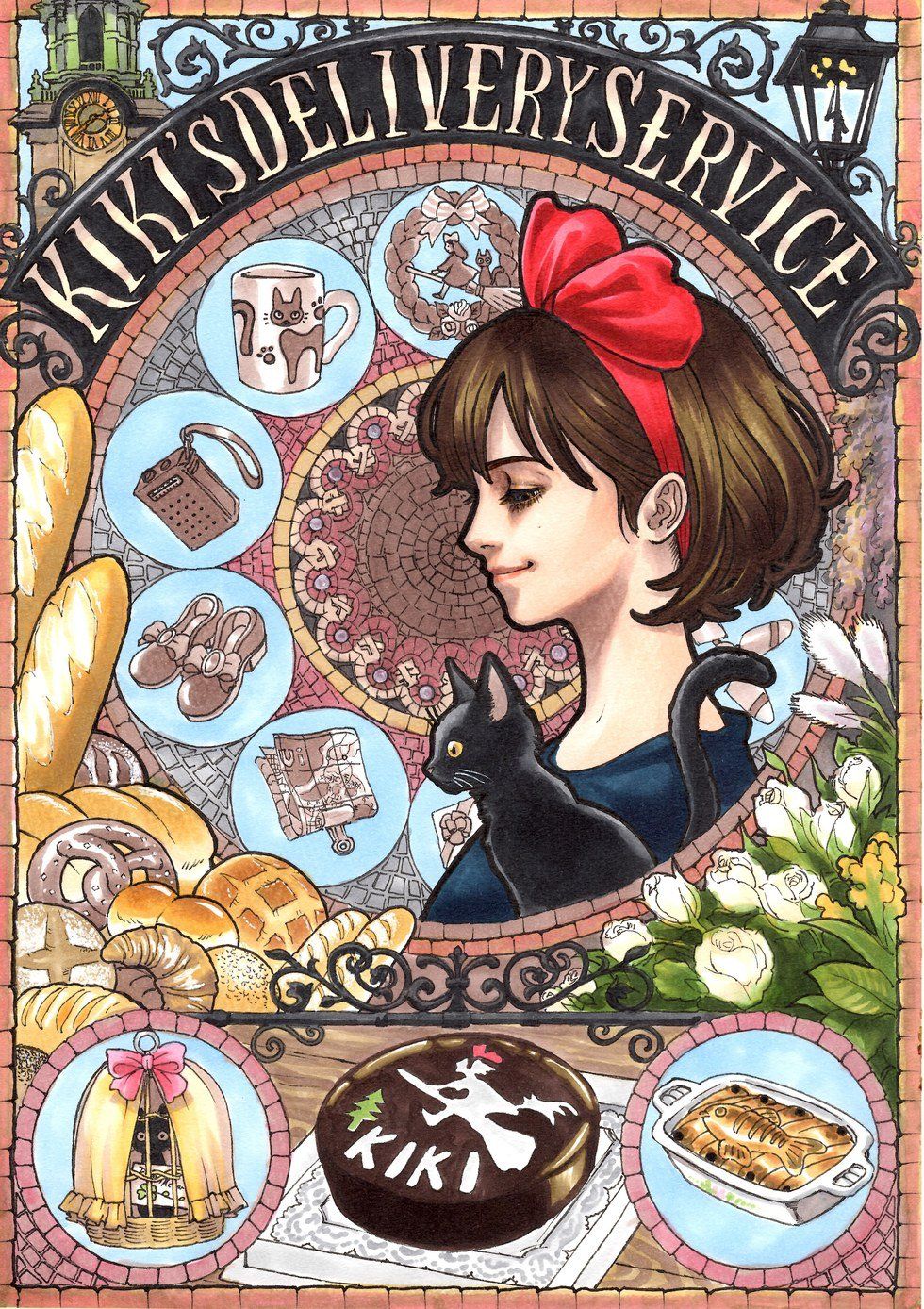

"Three Vases: L'Oignon and two marquetries sur verre" (c. 1900) by Emille Gallé, 1846-1904

The physical nature of how the Art Nouveau swept the world is surprisingly simplistic, like the style of the movement. It began with the Arts and Crafts Movement, a time in English history where design followed the ideologies of architect Augustus Pugin (1812-1852), writer John Ruskin (1819-1900), and artist William Morris (1834-1896). Designers from Belgium picked up the trends and twisted them to match their countries fashion. Once on the continent, France found immediate interest in the newly arrived style, and Germany followed suit. This historical movement really parallels old-world patterns of development, before bounded cities and countries were established. Cultures would stumble upon a remnants of others and amazingly inspire each other. Around the 18th century, art had decidedly become stagnant because people were not communicating as much with others. It didn’t help that artists were strictly ruled by their nations and held back by royal restrictions and critique.

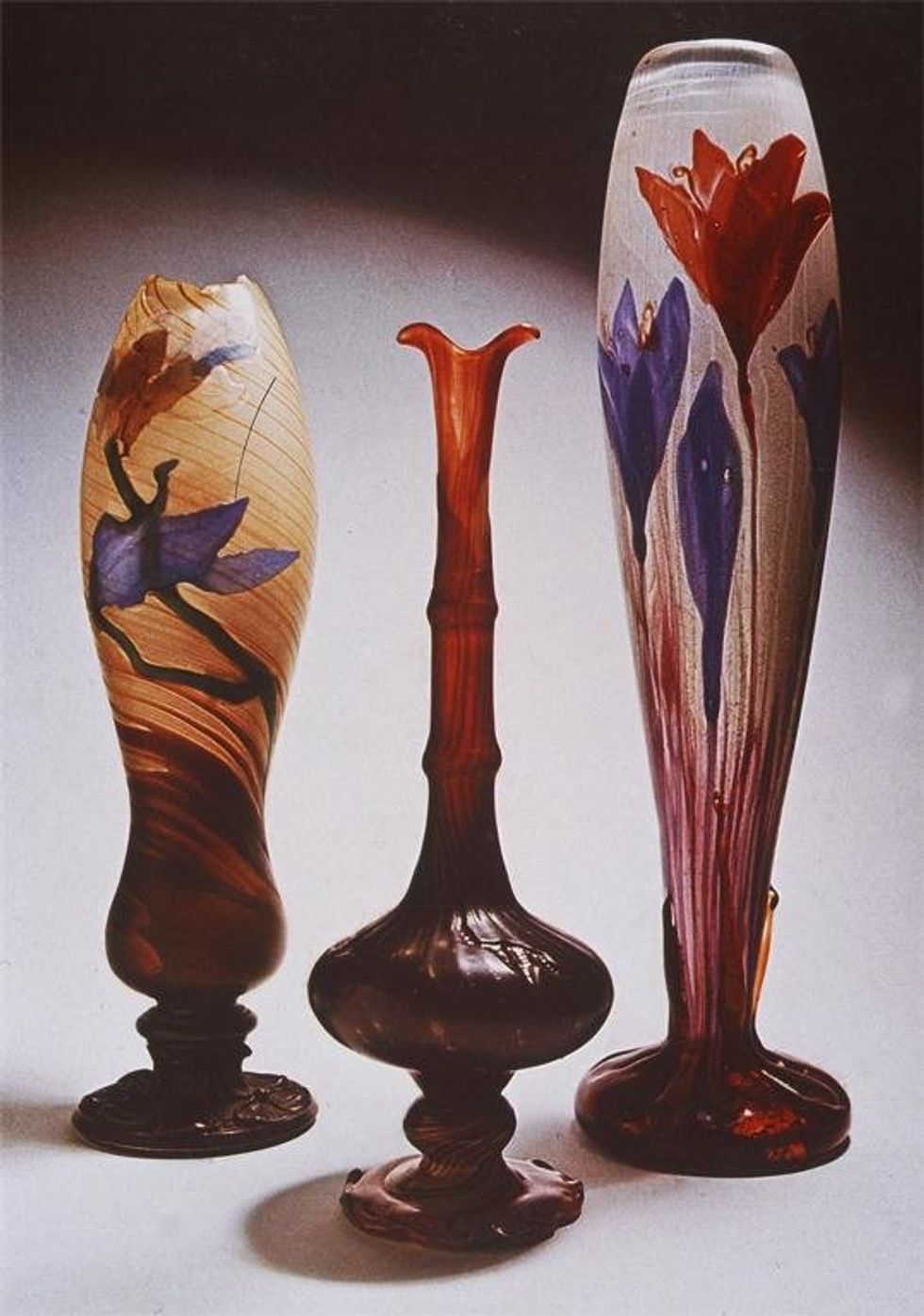

"Avenue Theater, A comedy of Sighs!" (1894) by Aubrey Beardsley, 1872-1898

Art Nouveau began unifying countries culturally once more, but also became a medium that helped nations communicate with each other. Businesses, artist groups, exhibitions, and magazines were constantly being formed with the quick rise of the movement. Companies were sharing the innovations added to the Nouveau style, especially those with Japanese influences, throughout the world. Artist groups all over the European continent were making appearances and were a symbolic representation of the rapid communication happening; there was enough talk about Art Nouveau to form namable groups, rather formulate titles for a group of artists connected through a style, like “The Impressionists.” Exhibitions, usually planned by these groups of artists, helped spread the word of Art Nouveau to the general public and gathered culturally different civilians in one place. Most amazingly, the appearance of magazines was easily mass produced way of international communication. Magazines not only shared the current Art Nouveau trends but explored the past of Art Nouveau; they preserve an important record of history for the time periods and countries that perhaps caught onto the trend a bit later.

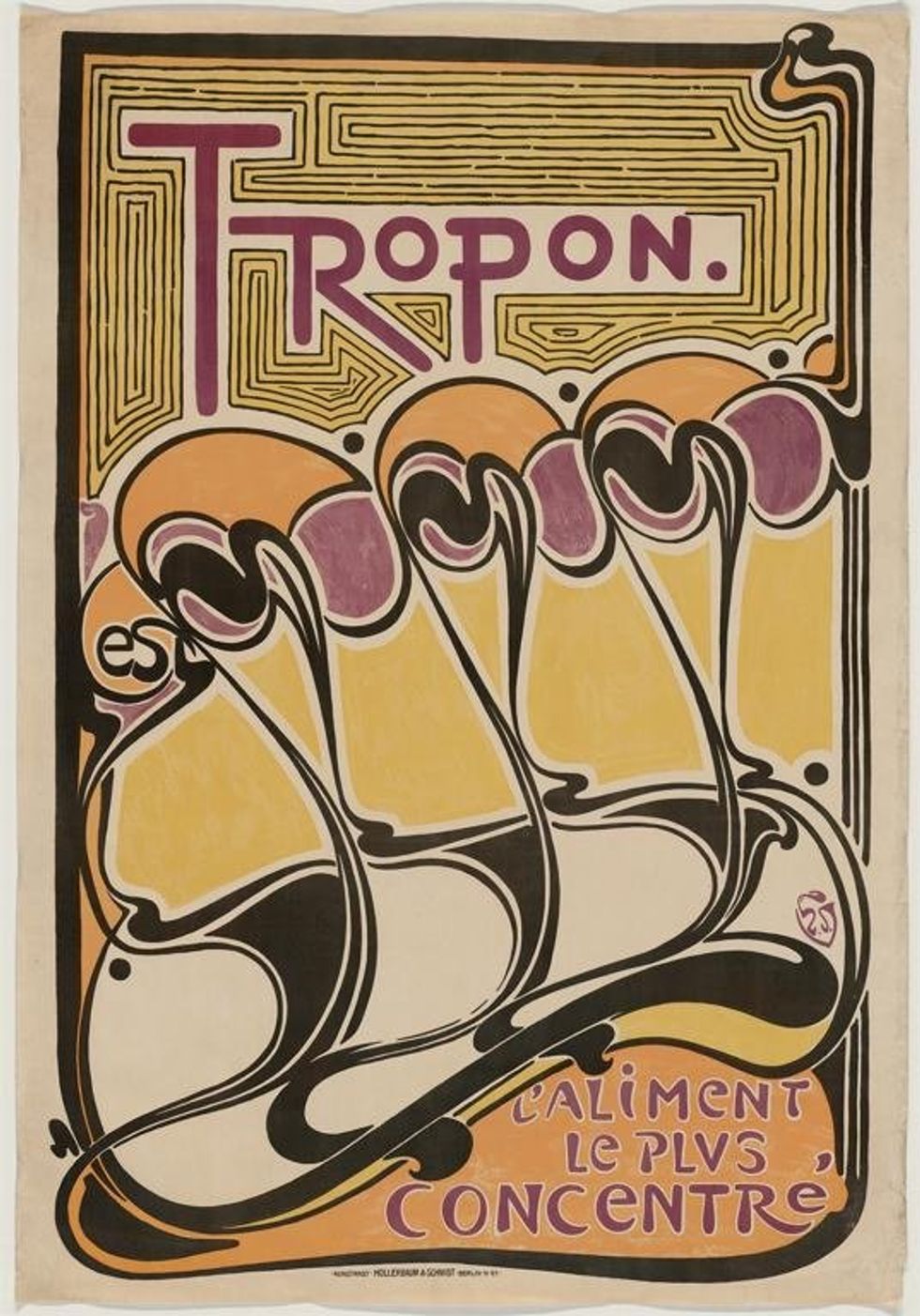

"Tropon, l'Aliment Le Plue Concentré" (1899) by Henry Clemens van de Velde, 1863-1947

Art Nouveau shows the beginnings of uniting the world once again, like when civilization first began, and expresses the root of art’s original message — that beauty is in everything.