In two years, the United States will be celebrating the 100 year anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which secured the right to vote for women. However, every woman was not able to vote beginning in 1920. African American women, in particular, were denied the right to vote for nearly 50 years afterward.

From its very dawn, the women's rights movement was grounded in racist rhetoric. At the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, a group of sixty-eight women and thirty-two men passed a declaration which stated, "[Mankind] has withheld from [womankind] her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men -- both natives and foreigners". Organizer and prominent suffragette Elizabeth Cady Stanton was known for publicly denouncing African-American men as "Sambos" and rapists. She was not alone in her views; many other white suffragettes, including Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt, also used racist rhetoric to win women the right to vote. It is also worth noting that the Seneca Falls Convention had only one African-American male attendee, and no women of color -- in fact, none were invited.

This racist rhetoric was not only troubling to African-American suffragettes -- who have been all but erased by history -- but also served as an extension of white supremacy in a nation where people of color were beginning to gain equal rights. Though Stanton, Anthony, and other suffragettes were also noted abolitionists before the passing of the 15th Amendment, which these women protested for its failure to include rights for all genders as well as all races. President of the National Women Suffrage Association, Anna Howard Shaw, stated that, by granting African American men the right to vote, "you have put the ballot in the hands of your black men, thus making them political superiors of white women. Never before in the history of the world have men made former slaves the political masters of their former mistresses!" Thus, after the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870, the women's suffrage movement took on a new tone: one that protested the rights of black men over white women, dragging these men done in the process. Some, like Susan B. Anthony, argued that if one group were given the right to vote, it should be white women; she famously said that she would rather "cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work for or demand the ballot for the negro and not the woman".

Many African-American suffragettes continued to work with white suffragettes despite this racist stance, hoping that their involvement would allow women of color to obtain equal rights along with, or at least after, white women. However, many white suffragettes banned African-Americans from attending their conventions and meeting, such as the 1901 and 1903 National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA) conventions in Atlanta and New Orleans. At a 1911 NAWSA national conference, president Shaw refused to denounce white supremacy at another member's request, stating that she did not want to anger other members of the movement. The Women's Journal, after publishing a letter to the editor which asked if there would be black participation in an upcoming NAWSA demonstration for women's suffrage, the organizers of the movement contacted the editor of the journal to request that she, "refrain from publishing anything which can possibly start that [negro] topic at this time", arguing that bringing in the issue of race would cause them to "lose absolutely all we have gained and more".

African-American suffragettes, while covered up by history, worked hard to advocate for the right of colored women to vote. At an 1867 convention of the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), black abolitionist and suffragette Sojourner Truth argued, "There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before." White suffragette Lucretia Mott, though once working next to Anthony and Stanton, split with their group after their opposition to the 15th Amendment. Lucy Stone was another such figure, and she, along with many other suffragettes, supported the ratification of the 15th Amendment, even if it meant women would have to wait before they won the right to vote.

African-American women were not the only group left behind by white suffragettes. Native American women, though they played a vital role in gaining women the right to vote, were unable to vote until 1924, with the passing of the Indian Citizenship Act. However, many states passed legislation prohibiting Native Americans from voting, keeping many from the polls until as late as 1948.

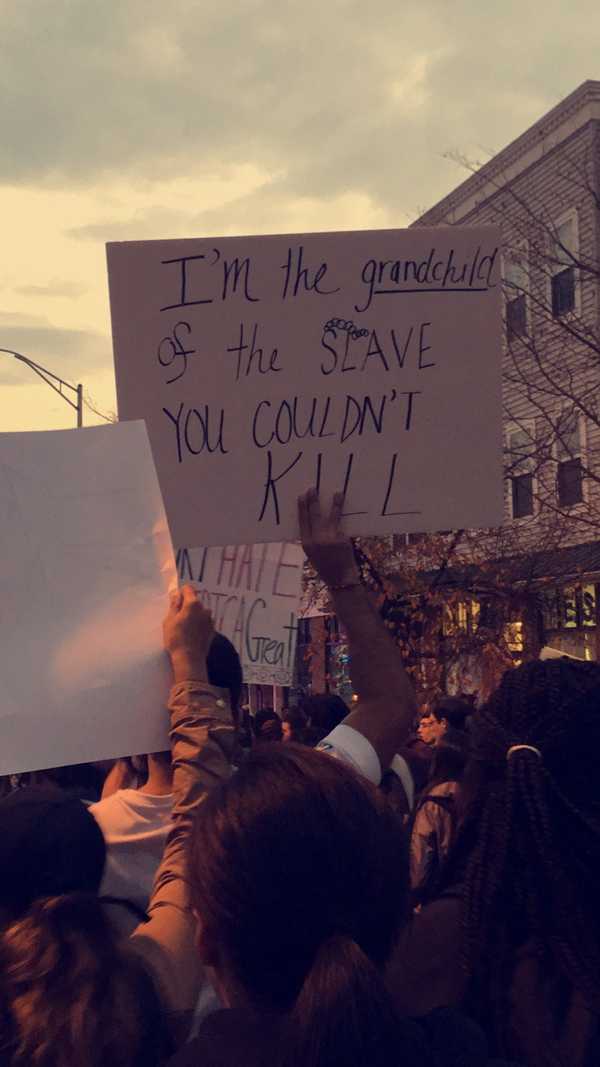

Though they have been denied the right to vote for longer than any other group, women of color have been exercising their right to vote in full force for the past nearly 60 years. In 2012, African-American women voted at a higher rate than any other group, playing a large role in determining the outcome of that year's presidential election. And movements such as Black Lives Matter and intersectional feminism are led strongly by African-American women.

So, on August 18, 2020, when the nation is celebrating the centennial anniversary of women gaining the right to vote, remember that this day is not an anniversary for all women. Some have had much less time to cast their ballots. And while you celebrate, make sure to note the racist history of the suffragette movement, and to empower women of color in your jubilations. Suffragettes of color and the sacrifices they, as well as women of color exercising their right to vote in the mid-1960s, made, cannot be forgotten.