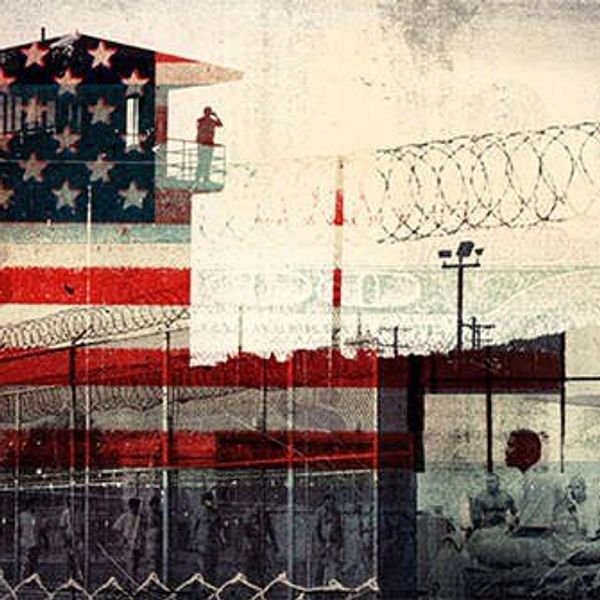

The Department of Justice has announced that it will no longer use private prisons to house federal prisoners any longer. Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates has called on the DoJ not to renew any contracts that expire and to “substantially reduce” the purview of any other contracts. Private prisons are a controversial subject in the United States. The industry underwent a rapid expansion in the 1980s under presidents Ronald Reagan and George H .W. Bush, and reached its peak in the 1990s during the term of Bill Clinton. Clinton’s plan was to cut the number of people on the federal government’s payroll by extending some control of prisoners to private businesses, and to deal with overcrowding in federal penitentiaries. The 1980s-1990s was also the time when the tough-on-crime policies that have come to shape America’s criminal-justice system were put in place, such as mandatory minimum sentencing and three-strikes laws. In recent years, tough-on-crime legislation has come under fire for its harshness when it comes to nonviolent drug offenses, and for the obstacles prisoners face once released. There has also been significant debate over racial bias in the legal system, as people of color, particularly black men, are far more likely to go prison and typically receive harsher sentences than white people who commit similar offenses. The DoJ’s decision to end the federal government’s relationship with private prisons appears to be yet another sign that the era of being tough-on-crime, regardless of the efficacy or consequences, is coming to an end. It is hopefully a start down a long and difficult road.

The thought of private prisons might leave most people uneasy. Profiting off of the incarceration of people seems like a shady business, but it became easy to argue that such an effort would reduce the taxpayer’s bill by lessening the financial burdens of running prisons on the federal government. And private prisons have become good business. The United States of America has the largest prison population in the world. Not per capita, just the largest prison population, period. The United States has 5 percent of the world’s population, and 25 percent of the world’s population behind bars. The growth of the number of Americans in prisons occurred, perhaps unsurprisingly, beginning in the 1980s. In 1978, two years before Ronald Reagan was elected, the prison population in the United States was around 300,000. In 2014, it was over 1,500,000. And despite the fall of violent crime rates since the 1990s, the increase in the prison population has continued.

There are many ills that plague the United States criminal justice system. Twenty to thirty years ago, being hard on crime was a political necessity, and in many ways it still is. While, under careful consideration and nuanced understanding, it becomes clear that lenience would benefit the American criminal justice system and society at large, it is a hard policy to sell. Tough-on-crime legislation is appealing; it signals strength and intolerance for actions that are harmful and detrimental to the public. Yet such policies have made the sentences for non-violent offenders much harsher than they should be, and have resulted in high rates of recidivism. A report by the United States Sentencing Commission found that, among a group of 25,431 federal prisoners, almost half were rearrested within eight years of release, and a quarter were reincarcerated over the same eight years.

Studies show that tough-on-crime policies have impacted black young men more than anyone else. According to a report by the Boston Globe, between 1979 and 2009, the chances of a white man ages 30-34 going to jail went from 1-3 percent. In that same time period, the odds of a black man going to jail rose from 9-21 percent. The story was even worse for black males who did not graduate high school. Nearly 70 percent of black men ages 30-34 that dropped out of high school went to prison in 2009.

For those involved in private prisons, from owners to investors to shareholders, these statistics are far from bad news. Troubling signs for American society are good for the accounting books of private prisons, and as the private prison population has grown, so has the private prison industry The rapid increase in the amount of prisoners has led to overcrowding in state penitentiaries, and inmates are being sent to private prisons in growing numbers. This change has been especially stark for federal prisons. In 1999, there were less than 4,000 federal prisoners in private prisons. In 2010, there were nearly 34,000. In that 20-year period, there was a 784 percent growth rate in the amount of federal prisoners in private prisons. In that same period the growth rate was 80 percent for private prisons at the state and federal level, compared to an 18 percent growth in the overall prison population.

These statistics from a 2012 report by the sentencing project show how the growth of the prison population has been a boon for private prisons. But why is such a bad thing? It’s obvious that the prison population increasing to the levels that it has is indicative of a broader problem in the United States, but what does it matter that prisoners spend time in private prisons? Firstly, there is the Econ 101 argument. By privatizing prisons, there is an incentive to lock people away, and the longer, the better, and private prison corporations lobby Congress for longer sentences. Then, there is the matter of prisoner labor. Prison labor has a long history in the United States, and a troubled one. During Reconstruction after the Civil War, many newly free black citizens were charged under laws known as Black Codes and “hired out” during there prison sentences, in what was essentially a continuation of slavery. And in at least 37 states, businesses can contract prison labor from private prisons. Companies such as Microsoft, Motorola, Boeing, Nordstrom’s, AT&T, and many other top tier United States corporations hire out prison labor. The labor is carried out in both private and government-run prison facilities, and while neither situation is good, it is far worse in private prisons. While prisoners in state penitentiaries earn around $200-$300 per month, the highest paid inmates in private prisons will receive only $60 per month, with most paid closer to $20. This paints a picture where there is incentive to lock up more Americans so that companies can get cheap labor from these prisoners. When all the components are observed together, added with the knowledge that private prisons have become a powerful lobbying force in Washington, the situation appears extremely troubling. The largest private prison company in the United States, the Corrections Corporation of America, wrote this in its 2014 annual report:

The demand for our facilities and services could be adversely affected by the relaxation of enforcement efforts, leniency in conviction or parole standards and sentencing practices or through the decriminalization of certain activities that are currently proscribed by our criminal laws.

Essentially, private prisons benefit from longer sentences, more prisoners, and stricter crime policies. They are actively trying to prevent meaningful and necessary reform in American policy on crime. There is no need to rehabilitate prisoners or ensure they will be productive members of society upon release; in fact, their appears to be an incentive to oppose such results. Private prisons are clearly lobbying against change for the criminal-justice system, and with larger corporations hiring cheap labor in such prisons, the amount of money and corporate interests behind such facilities is immense.

Then, there is the fact that private prisons have not significantly reduced the cost of caring for inmates, and create a far inferior environment than federal prisons. A report by the Inspector General of the Department of Justice found that private prisons, while costing less, were not transparent on whether or not they kept up with federal guidelines for prison environment, and therefore, the slightly lower cost per prisoner could not be seen as private prisons being more efficient than federal ones. This same report showed that in fact, private prisons did a worse job than federal prisons in numerous ways. There was more contraband found in private prisons than in federal ones, including weapons and cell phones. While the report did acknowledge that such a discrepancy could be due to more intense searching methods by private prisons, it noted that the difference in certain categories, particularly the amount of cell phones confiscated, indicated that the government needed to reevaluate its relationship with private prisons. When it came to violence, however, the report made it clear that private prisons perform far worse than federal ones. On average, inmates in private prisons committed 28 percent more violent assaults per-capita against their fellow inmates, and more than twice as many violent assaults on staff, than prisoners in federal institutions. The report also found that inmates were more likely to be disciplined for serious offenses, such as sexual assault or possessing weapons. All three private prisons that the DoJ observed received citations for one or more safety and security deficiencies while the study was being done.

In the end, the report concluded that private prisons “incurred more safety and security incidents per capita”, and that inmates were not receiving the care they would in a federal prison. Checklists for private prisons did not address requirements for health and correctional services stipulated both by contract and policy, and that they did not include adequate security measures. The Office of the Inspector General found, essentially, that private prisons were not fulfilling their obligations as correctional facilities. The report included several recommendations for prisons and the Bureau of Prisons, which monitors private prisons that are contracted with the DoJ, but the memo from the Deputy Attorney General indicates that the federal government will simply distance itself from private prisons. This is a step in the right direction, but only a step. The vast majority of inmates in private prisons are not in prisons contracted by the federal government, so this change does not eliminate the private prison industry in the United States. Corporations like CCA will still exact major influence on politicians and fight to keep their prisons full and Americans locked away. And as long as the tough-on-crime policies of the 1980s and 1990s remain, the systemic issues of the American criminal-justice system will remain a stain on this country. Criminals should pay for their crimes. That is necessary for civil society to exist. However, policies that limit the ability of felons, particularly nonviolent felons, to reenter society once they leave prison end up exacerbating the issue and often lead to more crime and rearrests. The United States is in the process of reevaluating its policies concerning crime, and here’s hoping that this will be the case after the national elections in November.