As I approach my senior year of college, I find myself reminiscing on earlier emotions fondly experienced back in the end of my high school career: crippling dread and extreme misery. Now, logically, this dread and misery should be directed at leaving college, moving on with life and having to do this little thing we aptly call “adulting.” Instead, I am fixated on the one thing I thought I left behind when I graduated from the entangled web of secondary education: Standardized testing.

Standardized testing. The nemesis of all students everywhere (unless you’re one of those people that naturally turns out perfect scores on some of the most meaningful exams in your life — then bully for you, I guess). But if you’re someone like me, whose palms leave sweaty imprints at the mention of testing on the wooden, too-small-to-fit-an-actual-human-being school chairs, then you’ll understand my problem. Aside from anecdotal evidence on why standardized testing is detrimental to student mental health and well-being, what exactly is the problem with these tests? And, most importantly, do we even have any evidence to show there is a problem?

Well, actually, yes. We have evidence. And there’s a lot of it. But really, I’m not going to go into it. I’m not going to list the countless times these issues have been pinpointed, like here and here and here, the continuous documentations of the detriments of standardized testing. I’m not going to tell you about the study by the Council of the Greater City Schools, which found that students take an average of eight standardized tests per year. And how, if we were to calculate the time sink for such a thing, assigning four hours to each standardized test, we’re looking at around 32 hours spent on standardized test taking each year. That's only the actual process of taking the test, of course, and not the tests in general. Because if we consider the preparation teachers are now expected to engage in prior to these tests, we soon see how the curriculum has transitioned from things such as the societal and political implications of Joseph Conrad’s "Heart of Darkness" to how best to select a multiple choice answer when you simply don’t understand the question (Popular opinion: choose Answer C — but I've also heard A, B, D and E might work).

I’m not going to talk about any of that, though. That evidence is already there for you to peruse at your own leisure.

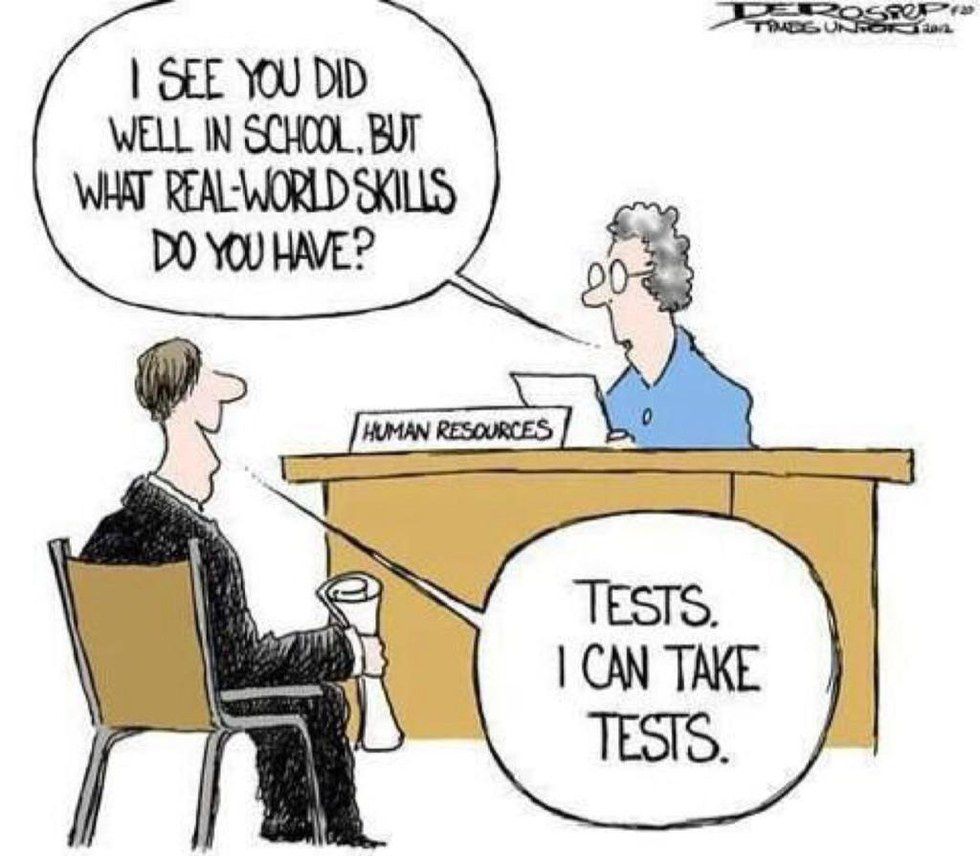

What I will talk about, however, is how these tests are not and never have been the purpose of school. We have striven for years to educate the next best minds of this generation, but we are falling flat in our endeavors. We educate students on how to score well. We tell them how to answer according to what the test is looking for, not how to think creatively or independently. We teach them their worth is contrived from number after number instead of developed organically through actual human characteristics.

After all the time spent teaching these testing techniques, there is not enough left for the curriculum that truly should be taught in schools. And we all thought it would end come high school graduation, but boy-oh-boy, were we wrong. If you’re considering education past the collegiate level, I regret to inform you that you will once again have to embark into the belly of the beast and fight your way through to the other side. Never mind the GPA you received, the coursework you took, your publications, your honor societies, your extracurriculars — none of that truly matters unless you can score well enough on a graduate school examination for them to even consider your application. So, you sit down, pull out the test prep book that you bought from the testing company, the same company that you incidentally paid 200 dollars in order to take their test, and you study. And you study. And you study.

But let me tell you what you’re studying. You’re studying how to effectively take the test. How to read the problems through the lens of whatever graduate examination the graduate schools you’re applying to force you to take. Then, when it’s all said and done, when the test is over and the scores are submitted, I encourage you to forget everything you just studied, because you will never again use it. Instead of spending those months buried in your prep book, you could have been reading. Writing. Paying better attention to your actual course materials (novel idea, I know). Learning new information in your chosen field of study. Doing anything except devoting time and energy to material that is both useless and not indicative of anything you have learned in your collegiate career.

But, that being said, I do finally know the relationship between X and Y when considering the triangle with points W, T, and F. And I’ll be certain to work it into my PhD dissertation on adverse impact in the workplace. Because, after all, graduate examinations are supposed to be indicative of graduate school preparation and success. So if I don’t make my knowledge of parallelograms known, then really, what kind of fraud am I?