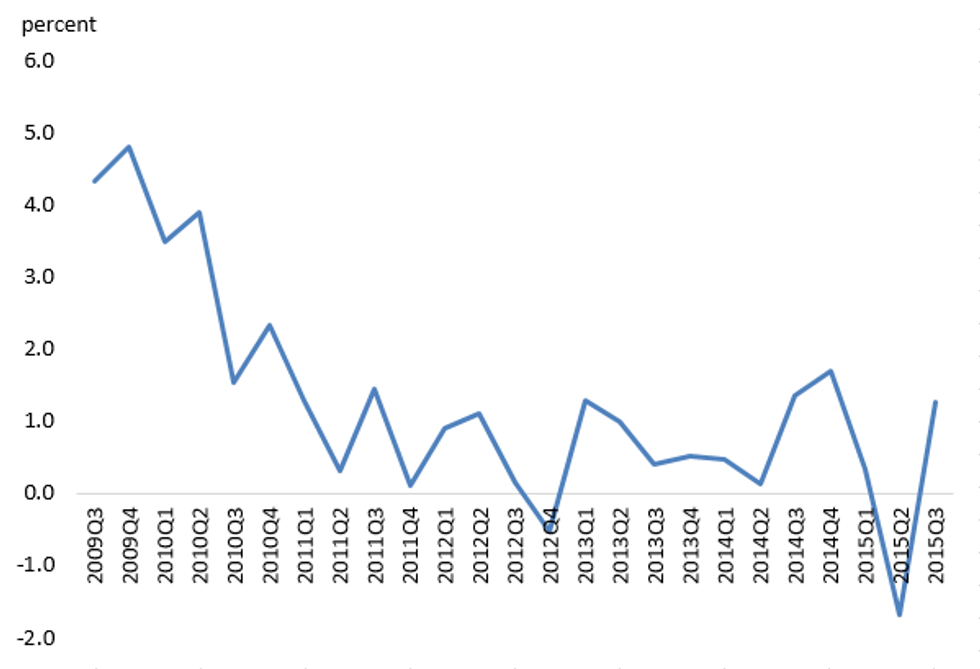

Global trade has reached a roadblock. First, the IMF released startling data showing that In the past five years, the growth in trade has been slower than GDP growth, a trend not seen in over four decades. Second, McKinsey has found that cross-border capital flows have stalled, pointing to diminishing international investment activity. Based on these numbers, it is clear that the cross-border exchanges have suffered a loss of productivity. Business leaders and economists are seeing this as a threat to the global economy.

Globalization in the 21st century is a monumental achievement five decades in the making. After World War II, peoples' incomes rose, transport became more rapid and cheaper, and demand for goods all over the world grew. When China opened its economy and when the Soviet Union collapsed, the pace commerce rocketed. And by the 1990s, the globe was experiencing a period of ‘hyperglobalization.’

But then came the crisis of 2008, which overturned decades of progress in globalization. Lately, recovery has been sluggish. Some are calling it “peak trade,” arguing that the apex of globalization was already passed.

But have we reached the expiration date for globalization? No. Instead, there is a revolution in global commerce. One driven by changes to developing markets, new consumer preferences, and technology

First, the post-2008 trends in trade are a sign of maturing economies. When China and the former Soviet Union were first absorbed into the global marketplace, their contributions to global trade were dramatic, as is the case when almost a billion people were suddenly integrated to a global network. But as they developed more sophisticated markets over time, their contributions to global exports decrease.

Second, the view that tightening global production lines is a sign of a potential economic downturn is wrong. Instead, businesses have readjusted their logistical models. Recently, businesses have moved towards producing closer to the consumers in response for online consumers’ appetite for shorter delivery times. If you’ve recently made purchases on Amazon, you are likely to be among the drivers of the trade revolution. Online distributors are racing to be the fastest shippers, which means changing their logistic models to create shorter supply chains.

Still, these global value chains remain a crucial element of production for many of today’s goods. Consider Nutella. To make one bottle requires hazelnut from Turkey, palm oil from Malaysia, sugar from Brazil and cocoa from Nigeria. The contents of one jar have passed through tens of thousands of hands and traveled across thousands of miles so that we have an excuse to eat frosting for breakfast.

Third, technology and the information revolution is changing the face of globalization. As data is able to travel through fiber optics an as components can be 3D printed at factories, physical goods from abroad become less important. And while the value of traded goods will diminish, the flow of information will add greater value to the global economy. Culture and ideas will proliferate. Individuals will grow more innovative. People will live healthier and more prosperous lives.

In this new era, the symbols of globalization will no longer be container ships or factories. It will be small businesses and the internet. The growth of trade will be contingent upon untapped sources of human capital and innovation -- much of which is seen on the African continent. Small companies in the U.S., which represent less than half of total export activity, are also poised be the drivers of American exports.

But for this to happen, there must be a global commitment to continue fostering healthy, competitive markets. Governments must start by breaking down trade barriers, which we see happen with free trade agreements such as TPP and TTIP. This will lower the costs of trade and boost small businesses’ ability to open to new markets. In developing economies, governments should encourage entrepreneurship by reducing taxes. Vocational programs and universities must also be able to equip the youth populous to enter a highly connected, technologically-driven workforce.

The inescapable truth is that the decline in the pace of trade among goods and services is likely permanent, it is important to accept that. But globalization has not ended -- rather, it is rapidly evolving.

In my view, I feel kind of bad for the people who took part in the Panama Canal expansion.

sunrise

StableDiffusion

sunrise

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion