"I’m a Fool for Jesus," my shirt read with "Whose Fool are You?" on the back. Hundreds of runners and spectators littered the hilly area surrounding the course, dressed in their team’s color. I wore a neutral white shirt to be different because I wanted to embrace my individuality. That is what attracted the curious, magnified eyes, peering through thick glasses.

“I like your shirt,” she said, dressed in a purple tie-dye with a cross printed on the front, an American flag waving behind it. She pointed to it as if expecting me to say the same to her. I just smiled. “Oh, nice.”

Recommended for you

“This is the shirt I’m going to be buried in.” She didn’t wait for a response as her mouth moved faster than the runners flying by, prattling on about the tradition of people dressing up to die. She laughed, but wasn’t joking, when she said she wanted to be buried in her blue jeans. As she came closer to me, I instinctively stepped away from her. Wrapping an arm around me as if to keep me from escaping, she started singing the hymn she wanted sung at her funeral.

I wish I could remember the ending to this story, but my focus was so fixed on the strangeness of this lady that I don’t recall the kindness she probably spoke to me. I remember this story not because it was funny but because I regret my response to it. I laughed at her because she was different. And I didn’t understand her.

In sociology, there is a term called “social hierarchy,” which ranks people based on their dominance within the society they live. People choose where they fall on the spectrum, their choices highly dependent on their personality as well as how other people treat them.

Denise Dellarosa Cummins, a psychologist and author, says that people judge fairness on where they are on the social scale. She said, “Our choices appear to be equally motivated by a desire for fairness as well as self-interest.” People judge others without realizing it, choosing whether it would be fair for them to associate with that person, or vice versa. There is a cost-benefit ratio that must be weighed before making acquaintances with certain people.

In middle school, I went to the annual band festival for our school, and we were waiting in a room with all the other bands before we went onstage. I noticed a couple people stray over from a corner in the room, while their friends turned their faces away and laughed, glancing a look from time to time. The two boys walked up to James, a skinny boy whose tux hung on him like on a hanger. His thin, black mustache made up of few random hairs rested noticeably on his top lip.

“Can I take your picture?” one of the boys asked, the other one trying to hide his laugh from behind his hand. “You remind me of someone I know.” James consented, and the boys took the picture back to the group where they all pointed at the phone, laughing.

I ran into James a few years later, after he graduated high school, and found out that he was making a lot of money with his very successful company. The kid that had few friends because he was different from everyone was suddenly flocked by people because he was rich. He went from the bottom of the social ladder to above those who made fun of him, and that changed how they treated him.

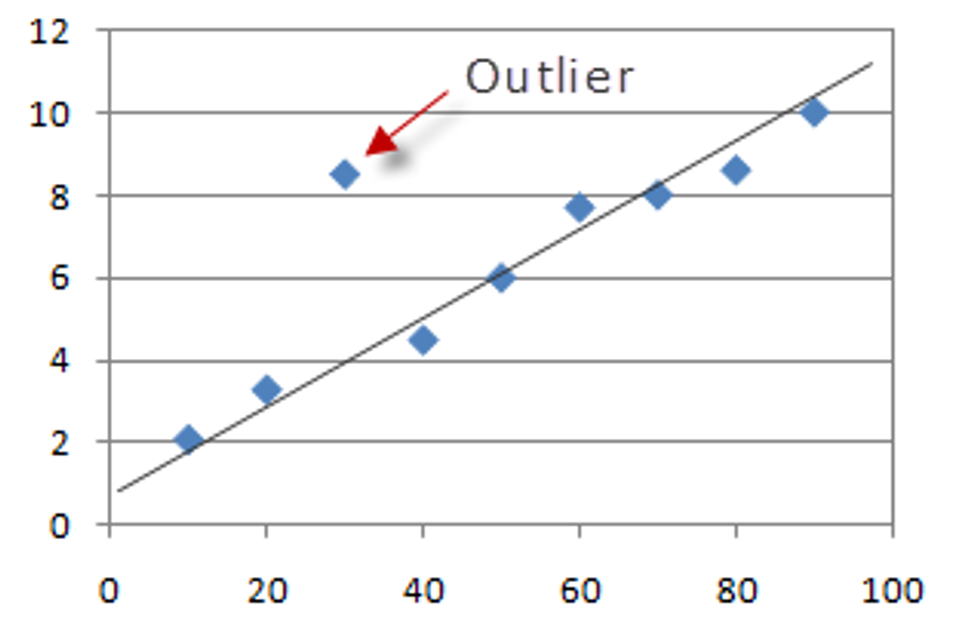

Cummins continues talking about social fairness by saying, “It would seem that we hold those of lower status to higher standards of behavior.” Because people don’t live up to the standards set by those on top, they are often mistreated or made fun of. Feeling the need to keep their place on the social high ground, people belittle those beneath them, putting them in a place that makes them feel like they are a burden to society; a social outlier. In math, an “outlier” refers to a statistic that surpasses the rest. An outlier is considered abnormal because it exceeds the parameters of the average, bringing attention to itself. In some ways, these people who are considered different or strange are surpassing the average person by embracing their diversity and refusing to be like the rest.

People are like piano keys, each possessing their own tone; unique to themselves. Some notes appear to sound louder when they are lower, drowning out the high notes, but they are relatively equal. A high C is not the same as the middle C because the pitch is different. All of the Cs on the piano can be played together, creating a harmony because they have the same tune. There are numerous harmonies that can be created by playing these different keys.

Dissonance can also be created from a chord of notes that do not play well together. Not every person is going to get along, and that’s okay. Each key has others that they harmonize with, and those they don’t. But the point is not that the keys are dependent on others to make a good sound, but that each key is beautiful within itself; creating its own tune.

The problem is that people listen to their own tune too often-- finding the beauty of their song-- that they fail to recognize the beauty of the other notes. In elementary school, I was an avid reader, devouring more books than meals, it seemed. We were reading a book in class, and one of the girls in my class said that she hated reading. She would make fun of books in general, along with all of their devoted admirers. Because she was considered the popular girl, always boisterously voicing her opinion, the rest of the class followed, and reading became a disease in the class. I, of course, not wanting to stick out as strange or nerdy, followed suit, giving up reading to please my classmates.

This led me to wonder why individuals value the opinion and approval of other people. What is it that stops me from dyeing my hair blue, singing off-key at the top of my lungs in the middle of a crowd, eating hot sauce with my ice-cream, or telling a joke that no one else would find funny.

Psychologist Saul McLeod discussed an individual’s self-concept, how people view themselves and their roles within a society. Self-image, how people view themselves, is determined by parents, friends, and personality. Self-esteem is measured by whether that view of them is good or bad in the eyes of the society. Self-esteem is influenced by the reaction of others, the comparison with others, social roles, and identity. Everyone possesses an ideal self, someone they could be but aren’t quite because of certain social or physical limitations. The ideal self is measured with self-image and incongruence abounds.

Almost everyone wishes they could be anyone but themselves. They see the shortfalls they think everyone notices, and they try to change the unchangeable by faking an identity that will please, but never does, a society that judges each other based on differences in personality, social status, or interests. But are these fair judgments?

One way that people cope with negative views of themselves is by perceiving others as having higher levels of that same negative trait. I may say to myself, “I’m so weird,” a comment that others may have said of me that I have claimed for myself. And I may look at someone else and say to myself, “At least I’m not as weird as that person.” Because I want to see the best in myself, I see the worst in others.

The problem maximizes when these negative comments become vocalized to the person I am judging. The effects of excluding individuals because they are different is much more serious than people think, or perhaps don’t think. The University of Georgia and San Diego State University did a study to show that social exclusion causes changes in an individual’s brain function and can result in neural limitations and inabilities. It starts with one act of exclusion, which triggers an absence of belonging for an individual, so the person excluded acts abnormal because they are treated thus.

I grew up with a kid, and I have seen the effects of exclusion through him. Adam was a little imbalanced to start out, and because of that, he was often neglected and shunned from friend groups. He had a very peculiar sense of humor, and he often sought attention in his misbehaviors. Class speeches and research papers showed that much of his time was dedicated to video games. All of his papers and speeches conveyed the same message: he was lonely.

Every act of exclusion was a door slammed in his face, putting him in a room further from everyone else. And some of these doors were locked, prohibiting him to pass back through. Some people that experience social exclusion never recover and remain in this state of abnormality. The more you wear down a piano key, the more out of tune it becomes.

The neural region affected by the distress of social exclusion, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), is the same region associated with physical pain. Every time Adam was rejected was like a slap in the face. And he was forced to turn the other cheek.

Not everyone that is excluded from social groups is affected neurologically. Those higher on the social hierarchy can cope with being rejected because they have another group they can join. Because they are not on the lower part of the hierarchy, they have the potential to build themselves back up by comparing themselves to the lower status people, pointing out the negative or different qualities of those people and making fun of them. When an individual’s self-esteem is threatened, that person can act out aggressively in order to feel better about himself.

Often when a person is insulted, his response is a reflection of his own feelings about himself more than the other person’s opinion of him. The act of exclusion sparks the feeling of insecurity, but ultimately, individuals have the potential to overcome people’s nasty comments by embracing who they are instead of trying to earn a sense of belonging. These people do not have the choice to turn the other cheek, but they have the potential to choose how painful the blow will be.

With every social exclusion, there is the potential for an internal self-rejection, where the reflections of peers are embraced as truth. The outcasts open another door after having one door slammed in their face, and they enter another room willingly, closing the door behind them. There they sit crouched on the floor in the empty room, alone. They knock at the door when they’ve recovered from the last rejection to ask the others to let them in. Maybe someone opens the door. But then it is eventually shut again, and they are pushed further from society.

How I respond to exclusion is a choice. My difference and abnormality may be the instigators of my exclusion, but just because the people that make fun of me are insecure, that doesn’t mean I have to be.

Sometimes I still find myself pushing away quirky people, and even after I know how it feels to be excluded, I fall into that vicious cycle of tearing down others to build up my self-esteem. Others’ insecurities cause me to feel insecure, which then causes me to make others feel insecure so I can feel secure. Does this mean there’s no hope for the excluded? Is it a continuous circle devouring the weakest people?

There is nothing more beautiful than individuals who are so secure in themselves that people’s opinions of them don’t matter. I was standing down on the gym floor, looking up into a crowd of young people, singing “How Great Is Our God.” Everyone in the bleachers stood stiffly, their mouths matching the words sung by the worship leader to my left. I could only hear the voices of the choir surrounding me. Blank faces stared at the words on the projector screen, their faces unmatched with the passion of the song. Every face seemed the same; an ordinary morning chapel expression.

As I scanned these expressionless people, one particular person on the top row caught my eye like the moon against a starry sky. A girl swayed to the music, her face tilted up toward the ceiling. Her eyes were closed, but they curved with her smile, forming smiles of their own. She held her hands high, waving them in rhythm with the music. Her mind wasn’t on the judgmental glances of the girls next to her or the boys snickering below her. She was in her own room, closed doors all around her. But instead of sitting on the floor, wishing to pass back through, she was dancing.