“God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?”

-Nietzsche

The idea of “God’s death,” popularized (though not introduced) by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, contrary to the simple statement of the notion, wasn’t intended to necessarily address a literal theological crisis, but a moral one instead. It was intended to analyze God’s place in the (then) modern Age of Enlightenment, and to rhetorically ask a question as to whether God was still a credible source of morality. To Nietzsche, because of his advancements, Man had outgrown the idea of God, thus killing him, creating the possibility, and for the sake of balance in the universe, the need, for Man to become God in his own right (rite). However, two centuries later, it can be seen that the vacuum left in the wake of God’s death has yet to be filled, that mankind has indeed killed God, and even worse, by not being in a position to emulate God, mankind has killed God in vain.

This year has been an interesting one. It’s been a year of apathy, of extreme views on all sides, and extreme measures taken by people to promote those views. It’s been a year of selfishness and separation, and it’s been a year that has served as an almost tangible representation of the fact that those that do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it, and not because of the election. The election is the least of what’s wrong with society, but right now, it is the manifestation of everything mankind’s created and let flourish up until this point, and because of this, many are starting to see even the act of voting as a limiting factor in an apathetic and programmed society, as opposed to a right of the free and sovereign. On a personal note, I’m not sure if things have always been this way, or if I am simply too young to know a world different than this one. However, even if it is indeed the latter, consider the implications for those that have spent even less time in this world.

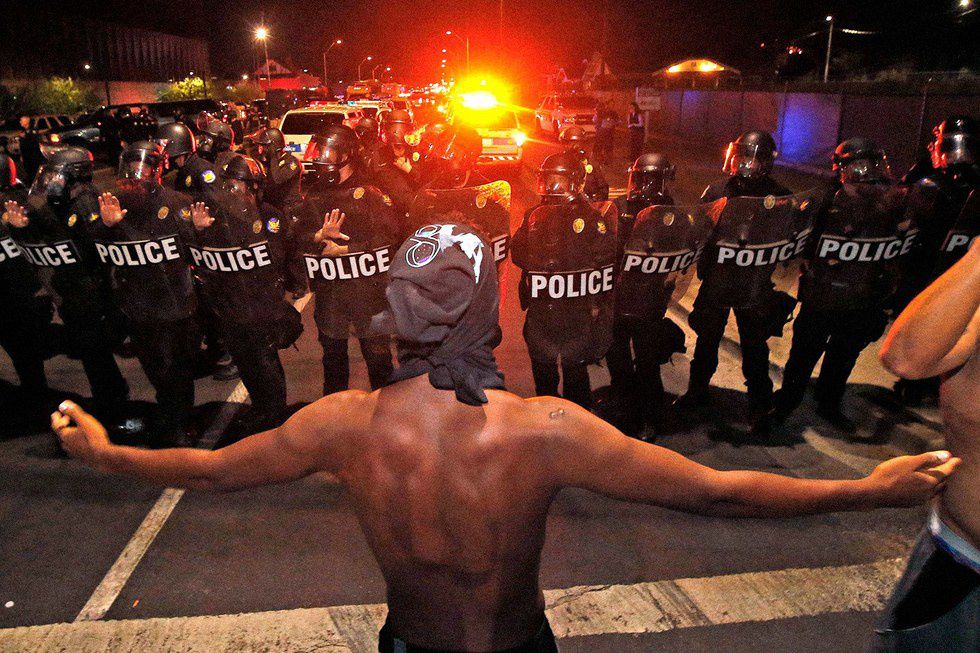

This narrative isn’t mean to be political, or at least not exclusively so. And though it seems pessimistic, the ironic fortune of not only living in a first-world country, but as such, having the freedom and platform by which to voice concerns is not lost upon me. However, if nothing else, that fact in and of itself furthers the points I’ve made. People enjoy the freedoms they’ve (we’ve) been afforded, but they (we) do so mindlessly, without examination of how these freedoms came about or the moral responsibility that comes with them. We go to school, we go to work, we sit in front of the television, we yell at newscasters with dissenting opinions, we vote, and we do all of these things in a cyclical fashion. For the most part, we are a society of law and order, and we abide by and maintain those things. Yet, what is the significance of law and order in a society devoid of a soul? In the last century, when it was legal, or at least legally permissible, for those in power to discriminate against others because of their ethnicity, did the legality of it make it morally permissible as well? And if not, then how do those principles apply in the modern age? If one sees injustice, is it permissible for that person to turn a blind eye simply out of fear of legal repercussions, or is it one’s duty to actively pursue what’s right morally, regardless?

Most would agree with the latter statement, fundamentally speaking. Yet, when it comes time to act, or at least to become informed and speak up, fear, either fear of consequences or fear of the unknown, paralyzes many, forcing them to instead align the former. Fear is a disease, and it is contagious to the point of being an epidemic in today’s society. Fear tells us that if we have a problem with society, the only thing we can do is vote, hoping that a solution will present itself. Fear tells us that when we witness injustice, whether at the hands of common people or those in authority, the best thing we can do is record the incident from a safe distance. Fear tells us that we’re allowed to care about others, but many times, it’s enough to care, and we don’t have an obligation to help others beyond our own statutes of convenience. This way of thinking, one based on fear, has ruled our society for too long, as has been made evident by recent events. Nietzsche may have been correct in his analysis of society. He may have been correct in positing that God is dead and that it is now our duty to restore hope to a world that’s been devoid of it for so long. That being said, I refuse to continue to let fear have any power in my life because there are good people in this society. However, good people that are silent when it matters don’t contribute to making society any better. We must become living examples of the changes we want to see in the world, and the only way we can do that is to refuse to be controlled by fear any longer.