Popular culture has been linked to politics since the beginning of civilization. Roman emperors would attend gladiator fights, writers would parody current events, and so on. In the modern era, one of the most politicized mediums has been, surprisingly, the comic book. With characters and stories like X-Men and Watchmen being used as political commentary in times of civil controversies and unrest, it usually comes down to just being a minor discussion, then we move onto something else. Yet this was not the case in post World War II America. In 1954 , Fredric Wertham, a child psychologist who often worked in crime-ridden and low-income areas, published his book Seduction of the Innocent, which stated that comics are the reason for children's involvement with criminal activity. The industry still sees some effects of this book and the controversy it started, and it translates very well to modern issues over pop culture.

During

World War II, comic books were among the most popular forms of

entertainment. They were cheap to produce, printed on newsprint type

paper, and could be recycled for the war effort or traded among

readers to get the most out of the books. Superman, Captain America,

Wonder Woman, and Namor all fought the Axis forces in the pages of

their respective titles. Crates of comics were sent to soldiers on

deployment, as it was cheaper to send a weekly box of comics with the

supply drops than it was a full USO show. Yet when the war ended,

sales began to drop. People no longer felt the need to have

larger-than-life heroes fighting villains on the four-color pages.

The superhero genre fell, though some characters were able to keep

popularity, most notably Batman and Superman, due to movie serials,

television (in the case of Superman), and radio. The stories started

to take a less violent turn, with many Batman

and Detective Comics

stories featuring Batman and Robin going against more “out-there”

villains – and of course, infamous scenes of the two sleeping in

the very close together beds in Wayne Manor. Characters like The Flash and the

Justice Society of America ceased publication within a few years

after the end of the war. Beyond the remaining superhero comics, the

most popular genres became Western, crime, and horror. EC Comics, the

publisher of the satire magazine/comic Mad,

was publishing graphic horror and crime comics such as Tales

from the Crypt and Crime

SuspenStories. These comics had

images of gruesome (for the time) violence and sexual innuendo, but

were still popular with children, as there was no laws/rules saying

kids couldn't purchase the books – often to the anger of parents.

Meanwhile,

Wertham had noticed the “obscene” images in the books, and saw

that the children at correctional facilities he worked in had

exposure or were regular readers of comics. He believed that Batman

and Robin were gay partners, that horror and crime comics were making

kids want to commit crime, and so on. His only claim that was never

really refuted was that Wonder Woman had heavy bondage messages,

which was actually true – her weakness was being tied up by a man,

and the creator, William Moulton Marston, completely intended for

this to be the meaning. In 195x, Wertham published his infamous book,

Seduction of the Innocent,

alleging that comics were ruining the minds of America's youth. The

book was a major success, selling countless copies, all while

beginning to scare the industry, dominated at this point by DC

Comics, EC, and Charlton Comics (Marvel was under the name of Atlas,

and a minor company after the war). Sales fell even further, some

shops refused to sell comics to minors, people gathered to burn

stacks of comics in public. Despite the book's success, there are

countless issues with Wertham's findings – he used a single sample

size of only children at behavioral or other mental health facilities

for his investigation; he did not actually read many of the comics

themselves, only looking at selected panels without context; used

only titles to gather information, among other logical missteps. This

caught the attention of Congress, who organized a committee to hear

the cases made by Wertham in 1955.

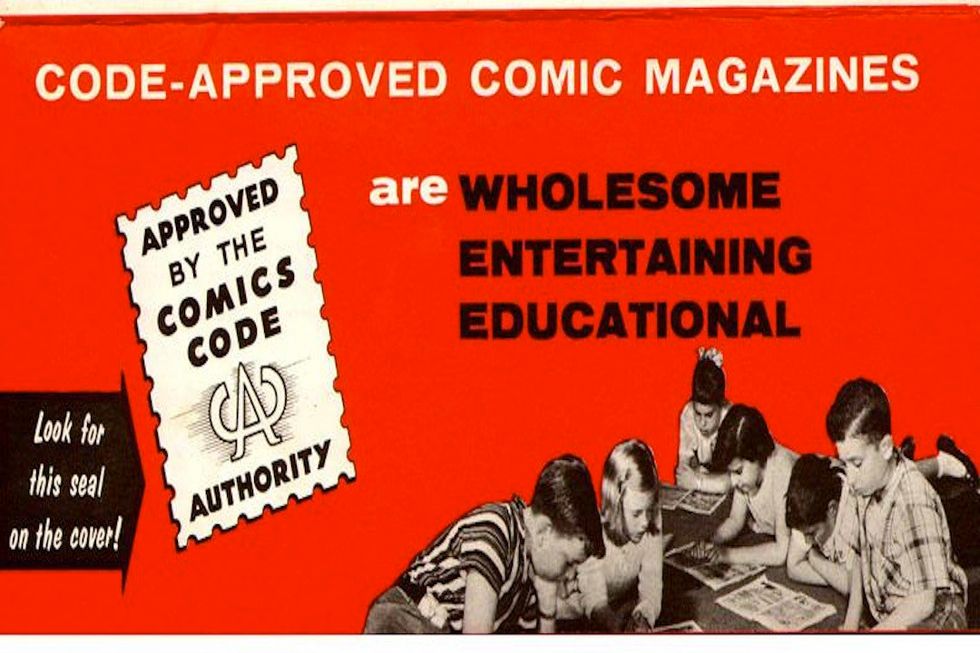

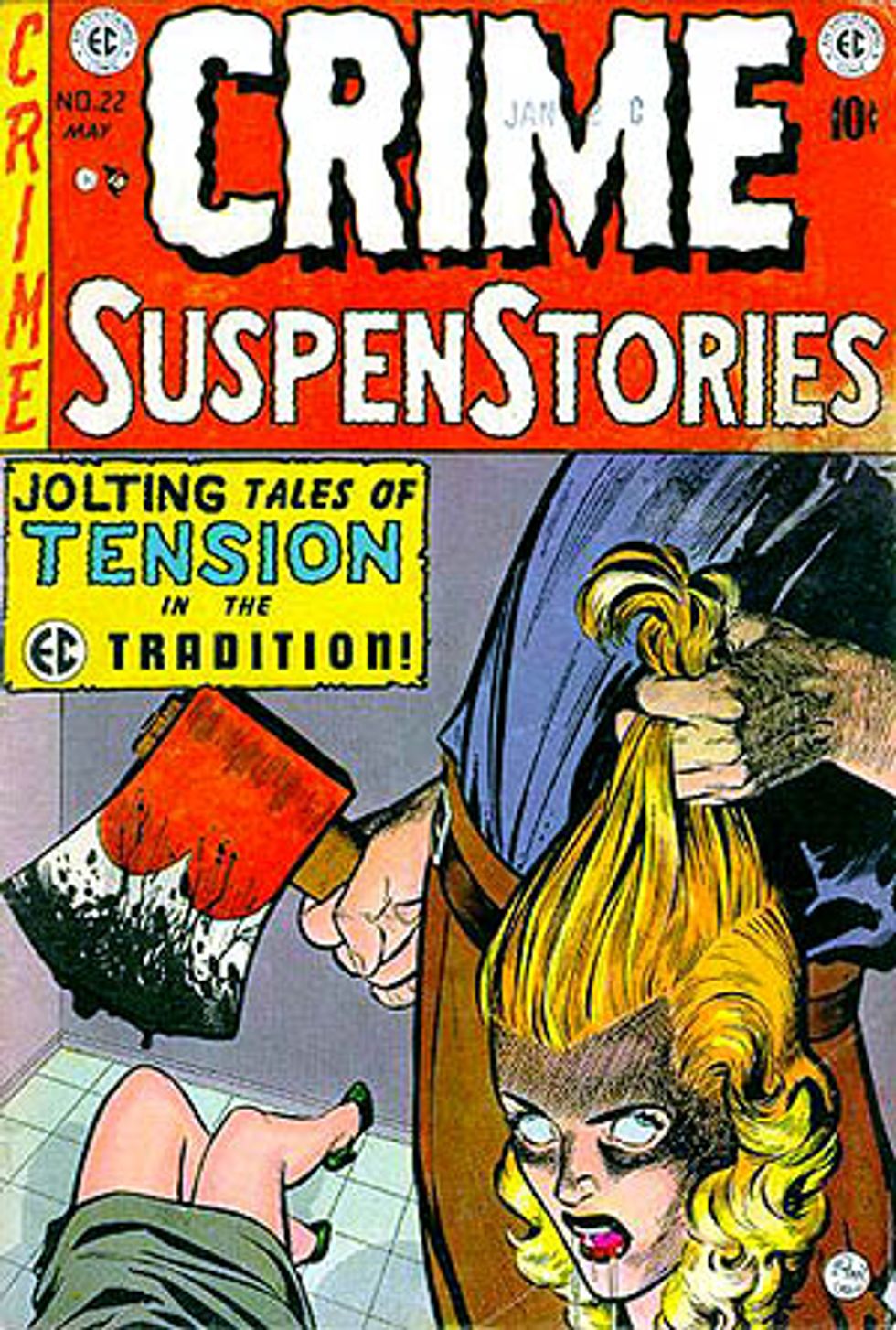

During

the Congressional hearings, publishers were called in to testify.

William Gaines, the man in charge of EC, was asked if his

publications were in “bad taste.” He famously argued that they

were in fact good taste,

because while cover of one of his comics that showed a decapitated

head, Crime SuspenStories #22, the gore wasn't too extreme. When the committee said there was

in fact blood dripping from the mouth, Gaines simply responded by

saying “a little.” Internally at the companies' offices, meetings

and discussions were being had over what to do. They didn't want the

government to interfere in their work, but they also wanted to be

able to stay in business. The major publishers got together, and

decided that in order to save themselves, they have to personally be

policing their works. The Comics Code Authority was formed in 1954

and put strict regulations on the content, such as no depictions of

drugs and that good must always triumph over evil in the end. This

was strictly voluntary with no legal requirement, but publishers

stuck to it for the sake of keeping themselves clean. As this was

done during the early days of the investigations, some publishers

used this as a way of showing Congress that they will be policing

their content. The committee elected to let the companies be, and

Wertham's credibility was being called into question. This, coupled

with the first appearance of the new Flash in Showcase #4,

started the Silver Age of Comic Books, lasting until the early 1970s.

All was not well though with EC, and due to the backlash over their

stories and Gaines' opposition to the Comics Code, the company went

bankrupt in 1956, selling off all assets to other publishers.

Of

course, this instantly became very limiting on what the writers could

do. For example, any

drug reference would make the comic “non-approved,” thus leading

to a general lack of major PSA comics about drug abuse. Gay

characters were strictly forbidden, as was any mention of sexuality

beyond dating or marriage. Even certain words were banned, like

“zombie” and “wolfman.” This led to a 1970 incident the

Comics Code not approving a story in House of Secrets #83

written by Marv Wolfman, as the story started by saying it was told

by a “wolfman.” DC argued that if it was made clear that the

actual writer's name

was legally Wolfman, the Code would have to approve it. They agreed,

DC started to give credit to writers (something they were not really

known for) – and in the end, the Code allowed for the horror-type

words to be used, paving the way for Marvel's Werewolf By

Night. On the drug/alcohol

issue, Stan Lee was commissioned by the United States government to

write a mainstream anti-drug story featuring one of Marvel's popular

characters. He went on to write Amazing Spider-Man #--,

in which Harry Osborn, the second Green Goblin, dies of a drug

overdose – the Code would not approve the issue, so it was

published without the seal of approval. The success of the issue

caused the ruling to be changed, so as long as drugs were seen as a

bad thing, they were allowed in, thus leading to DC's 1971 iconic

“Snowbirds Don't Fly” in Green Lantern/Green Arrow

#85-86.

Slowly,

the Code became more and more relaxed. It more or less became a

“well, if you want to” kind of approval – if it was sent

through, it would get the seal and maybe a “parental guidence

suggested” label for the shop to put up, if that. Dark Horse Comics

rarely sent in their publications, as they allowed any writer/artist

to put out anything and keep all rights (that's a different story for

another time). Around 2001, Marvel abandoned the use of the Code and

instead created their own rating system – All Audiences, Teen,

Parental Advisory, and MAX, the latter of which was reserved for a

specific imprint that included the hit Punisher

relaunch and Alias (the

first series to feature Jessica Jones). MAX comics were darker, and

sold only to adults, oftentimes being kept behind the counter away

from the other titles as to not be accidentally handled by a child.

At the other companies, comic stories were also getting more

adult/teen centric, but the Code let anything through with few

exceptions. DC, Archie, and Bongo (publishers of The

Simpsons comics) continued to

send comics in, but the Comic Code Authority's staff left the group,

leaving only a single person to read everything over. Bongo left the

use of the Code in 2010, and by early 2011, DC also left the Code,

using their own form of the Marvel ratings system, followed shortly

by Archie, thus ending the Comics Code Authority altogether. Longtime

opponent of movements and books like Seduction of the

Innocent, the Comic Book Legal

Defense Fund (CBLDF) bought the copyright to the Comics Code name and

logo, using it in their works usually in parody or to symbolize

hysteria over comic content.

Fast

forward to now. While there are not too many organizations against

comic books, many find other mediums to argue against. Video game

violence has been a debate ever since the release of Doom

and Columbine, Internet security and safety is constantly discussed

in schools, and even movies and television shows are met with

controversy. The Netflix series 13 Reasons Why is

being banned from talking about in schools, groups are calling for

Netflix to take down the show, and some even wanting to make it set

up so that only users over 18 can see it – which really doesn't

make sense, considering most people under 18 are simply using a

profile on an account paid for by someone else. The problem is not

the content, but the context in which said content is shown. A comic

book such as the horror series Escape from Jesus Island

is targeted to an older audience, and if you're buying it for the

first time in a comic shop, without a doubt they'll tell you that

it's very graphic and disturbing. Really, it just comes down to what

the reader/viewer is comfortable with – if you don't like graphic

violence, don't watch Game of Thrones,

but if you do, then go for it. Groups like the Comics Code Authority,

while helpful and a decent check system, usually end up completely

ruining creativity, as stories must be “safe.” We'll always have

our media controversies, and eventually, they'll just be seen as a

small aspect of the overall cultural history – something that is

always evolving.