Seeing the aftermath of Hurricane Matthew in Haiti, one would imagine that the natural disaster came a little too soon. The effects of the last disaster were still visible: as late as January 2015, approximately 80,000 people were still living in tent camps, and only 67 percent of those residents had access to latrines. However, “a little too soon” seems like a stretch upon realization that the devastating earthquake happened in 2010, around six years ago.

In spite of millions of dollars in aid from around the world, Haiti was still getting back on its feet when the hurricane knocked the country back down into crisis. Besides the devastating infrastructure damage and death toll, cholera and loss of communication plagued the survivors––especially in the south of Haiti. But all these problems were really there before the hurricane hit, and now they’ve just become so much more difficult to solve. What’s changed from the 2010 earthquake is the fact that the government has demanded that it take the lead role in recovery and sustainable reconstruction.

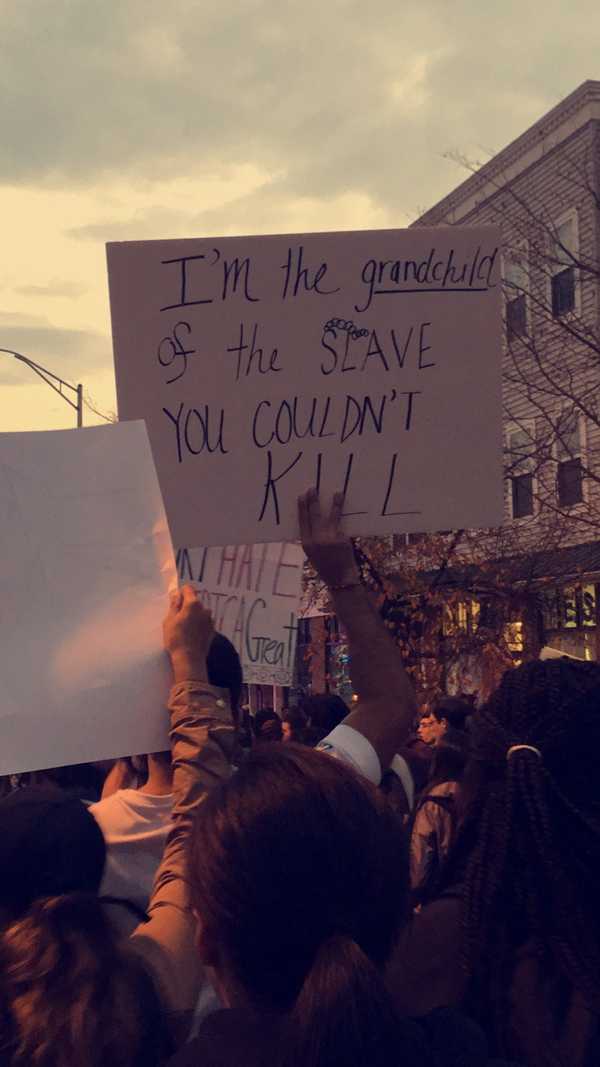

Image linked from: boston.com

The Haitian government’s experiences with the 2010 earthquake made it clear just why foreign aid from charity and nonprofit groups is a double–edged sword. Donor organizations like USAID and nonprofits like the Red Cross show their competence in immediate response, providing temporary shelter and food to the survivors. Rebuilding the infrastructure needed to let Haiti become stable again is not their specialty; neither is cooperation with the government, since “donor nations and nongovernmental organizations insist on keeping control of their projects, which are set according to their own priorities.” Thus, all the foreign funding goes into temporary relief, leaving little for the coffers of the government’s agencies that are actually responsible for sustainable development.

The government, drawing again from the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake, is well–aware of the logistical nightmare that these organizations create. Waste and inefficiency are chronic problems of these foreign organizations. Contractors and other international groups “fly in, rent hotels and cars, and spend USAID allowances for food and cost–of–living expenses.” That’s not even delving into the additional “danger pay and hardship pay” that inflate salaries by over 50 percent. These same contractors can be expected to build a house unit costing $33,000, when local contractors can do the same for a fifth of the price.

Of course, foreign organizations have a good reason not to trust the government with the funds. The long–running issue with bitter elections in Haiti’s government has put a lot of lawmaking on hold. An interim president, Jocelerme Privert, has been leading the country since the departure of President Michel Martelly; the opposition that lost the election last year has successfully pushed for a redo after evidence was found of fraud. Hurricane Matthew has stalled that election and pushed back the date, meaning that a polarized government of questioned legitimacy will be dealing on the disaster’s aftermath until then.

As an example of just how much faith the United Nations has in the ability of the government, the U.N.’s coordinator for the campaign against cholera in Haiti, Pedro Medrano, stated in 2015 that it will take 40 years to eliminate cholera in the country. While the fact that U.N. personnel were responsible for the cholera epidemic in the first place shouldn’t be ignored, their claim demonstrates some truth about the inability of the government to pass necessary legislation.

Image linked from: voanews.com

Considering all these factors, one may look upon Haiti as this black hole, in which funds and hopes go in and nothing comes out of it. And it’s true that things would’ve improved had it not been for the election troubles, foreign aid inefficiencies, cholera outbreaks, and chronic failure of communication in politics. That’s not to say Haiti is going to wind up a perpetually ruined country. Now that we know the logistical mistakes were in the past six years, we know exactly how to fix the response strategy to the crisis.

Haiti should be for us a learning experience in how to pull a country back from the brink, help it sustain its stability, and set it on a course for growth.