Last summer, I geared up for another long trek to the city. Sweat dripped heavily from my body like blood after battle, and I was sun-beaten to the point of heat stroke. It felt like a deadly, 60-day trek.

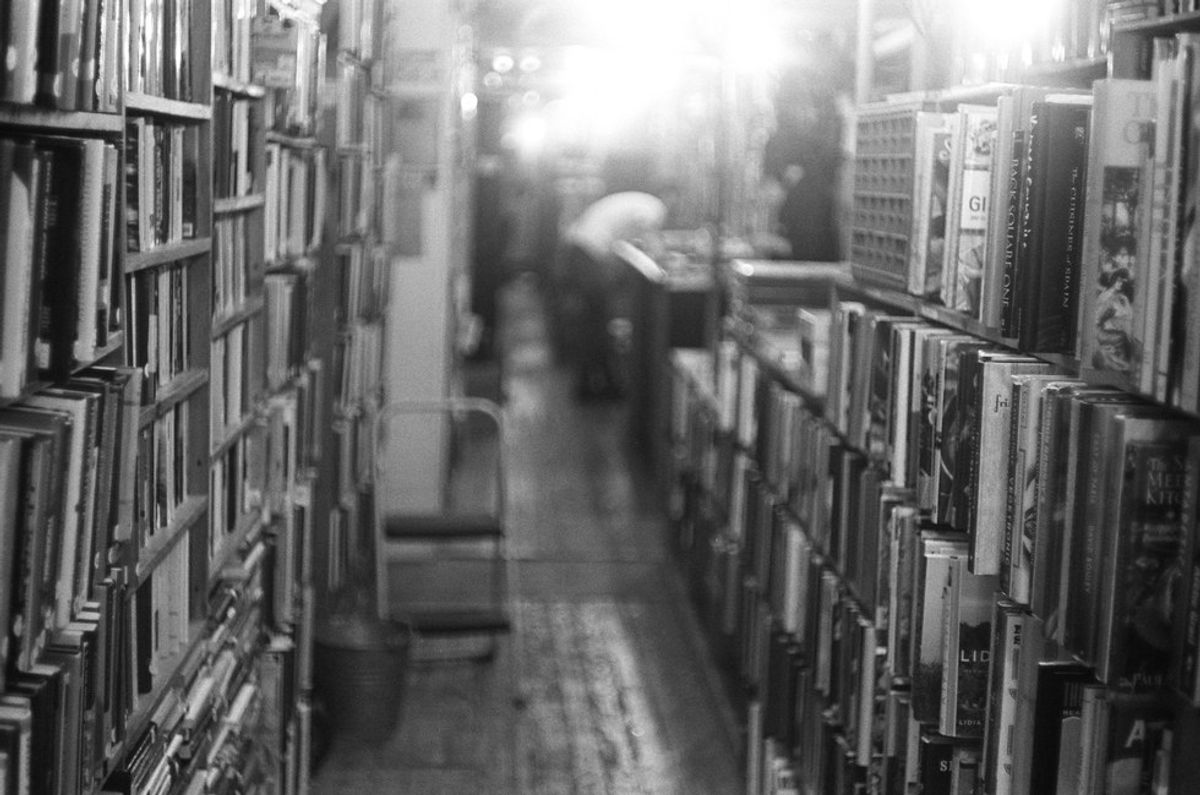

Thankfully the unibrow never grew and my sun-bruised skin found its way to the bookshop. But the walk from one bookstore to another was indeed a trek. The once vibrant Book Row of Manhattan dwindled after the many tenants had scattered or faded away over the years. What remained of the bookshop cavalry survived the recession, battled (or befriended) the landlord, stood tall against corporate bookstores and even climbed on the online book selling wagon alongside digital booksellers. Literary Mom and Pop shops are surviving and thriving, but New York’s literary battles are far from over. Nowadays, their problems are much more complex and we can’t just point fingers at the landlord anymore.

“The past 15-plus or so years [have been] quite challenging for smaller brick and mortar stores,” says Mr. Chris Lenahan, manager and buyer of the Corner Bookstore on Madison Avenue. “First the large discount stores, then online retailing…finally the appearance of e-readers and tablets (and let's not forget the financial meltdown.)” The 37-year-old Corner Bookstore is one of the few bookstores left on the Upper East Side. Since the 1950s, 280 bookstores have shut down in Manhattan alone. Some closings were reportedly affected by the opening of a nearby Barnes and Noble; many are victimized by the wretch that is rent increase, while others relocated then eventually shut down.

As for Greenwich Village, a professor from the New School recalls a much more occupied 14th St. “When I first lived in this neighborhood there were probably a dozen and a half bookstores within a 15-minute walk from where we’re sitting,” says the professor. “Now there are one…two…three maybe. A lot of bookstores have gone out of business.”

Further downtown on Allen St., Zyad Hammad, a staff member at Bluestockings, touches on the issue of readership and the role of technology on the falling literary market. “I can't speak as an expert ,but this is what I've overheard and experienced a little bit of. Readership has changed. I think it has. People are looking to pay less for books, which means there are more electronic books which starves the market even more.” Barnes and Noble’s Nooks and Amazon’s Kindles promise your entire library collection in one convenient device for a fraction of a price. But Mr. Thomas, manager of Crawford Doyle Bookstore on Madison Ave., argues that e-readers are far from effective. “It is my own hunch that something read on a screen is less memorable than something read on a page,” he says. “I think memory is connected with physicality. But I have no evidence of that. I don't know what the future holds.” The platform in which the story is presented is just as important when it comes to stabilizing or otherwise destabilizing the market. Will e-readers push physical books to extinction?

As much as literature relies on the individuals that sell and buy, rightly, so does it rely on the individuals that create the content as well as the individuals who publish it. Unfortunately, even theyare struggling as much as everyone else is. The artists, in fact, are struggling now more than ever. A professor at the New School and a novelist himself, Professor Neil Gordon explains the truth behind the troubles of the literary market and the obstacles that writers today have to face. “It's becoming much harder to be a serious writer, it's becoming much harder to be published. I'm sure the statistics will show you that fewer and fewer novels of literary depth and substance are published every year since 1990.” Most publishers, he says, are more interested with a novel that sells quantities among quantities, leaving quality literature to the dust. However, the blame can't be brought completely on the publisher; they too are up in arms with their own literary battles. “The economy has been very bad for publishing. Yes, it's become much worse…the explanation of why does not draw on me as a writer,” Professor Gordon states, “but it draws on me as a person who knows the business. Just as there are so many fewer independent bookstores there are very few independent publishers. Most big publishers belong to multi-million corporations and they are held to a consideration of the bottom line, much more than they used to.” The many different phases of the literary world invoke a large problem with too many sides to the story that a solution seems to be out of the question. But many people remain, and those that have survived the worst in the business are optimistic and the new arrivals are hopeful.

Founded in 2004, McNally Jackson bookshop is one of the city’s main literary hubs. McNally has its own café, and the shop hosts events, from workshops and readings to book clubs. The store also has its own printing press machine with services such as printing some titles in-store on demand. “For bookstores I think [their] success depends on doing everything an online retailer or a national chain can't or couldn't do,” says Matt Pieknik, the marketing director/social media account manager/European literature, play and theater overseer that sits on a table on the main floor with the “ask me anything” sign. Mr. Pieknik shares that as a child, “I didn't just read, I read voraciously. I ate books. Some of the few picture books I've still got have teeth marks on them.” He came to New York wanting to become a playwright. He explains that an existential crisis led him to browse the McNally & Jackson shelves often, hoping to find an answer to his predicament. Seeing no end to it, he realized that the problem was “less an existential one and more because I wasn't working here [McNally]…the rest is history.” As for the future of the literary business, he’s honest but optimistic. “Good writers and good books aren't going anywhere. In short, for the corporate people at the top it's still fine, and for the people at the bottom it's still a struggle.”

Similar to that walk Uptown on what felt like a 60-day trek through the desert, the literary battle is long, tiring, and endless. The question of how long will bookstores last remains unanswered. Will books eventually lose their depth and substance? The literary gods only know. Hemingway may pound his fists in rage and Salinger might protest with his Glass children, but the desire to keep the written word alive is not enough to keep it from being killed. Therefore, run to the nearest mom and pop shop, smack the young bloke that thinks he can't write the next "War and Peace," and smell the aroma from a newly printed hardcover. The ecstasy is worth the trek.

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by