Every year at the Olympics, new world records are set. This comes with our advances in training, nutrition, psychology and technology. World records today are escalated to a point of no comparison with the past, but how can we compare athletes with the legends of our history?

It is evident that the technology of our day has advanced to great heights, to what extent has technology affected the performance of today's athletes? Basically, the main question here is: Are our top competitors really better than the legends of the past?

Award winning sports documentary, ‘The Equalizer,’ puts this hypothesis to the test in comparing five of our most talented athletes in the 2016 Olympics with past legends.

In the sports documentary, top UK sports scientist Steve Haake travels to Canada, the US and Germany to meet five world-class athletes and investigate the effect that technology has on enhancing performance. Haake examines how technology has impacted each sport, taking into account the variables such as enhanced athletic clothing, shoes, surfaces, and equipment. For the first time ever, Haake equalizes the playing field by challenging the athletes to compete against a legendary athlete, but this time using the equipment from the olden days.

Of course, there are other factors that Haake needed to take into consideration, such as training, psychology, nutrition and competition. Grasse was not accustomed to running in these conditions, and the lack of competition could have affected his motivation levels. Haake would need to take these into consideration in his next athletic test.

Up next is American cyclist Sarah Hammer, who holds the current world record for the 3000m bicycle individual pursuit. Her time, 3:22.269 minutes is compared to Beryl Burton, a British cyclist who dominated women’s racing in the 1960s. Burton won seven world titles in her time, and was a five-time 3000m pursuit champion. Hammer is challenged to beat her old record using a vintage bike and smaller helmet, becoming overall less efficient with each revolution and less aerodynamic in her positioning on the bike. Hammer completes the course, beating Burton’s time by over 10 seconds and giving Haake hope for the athletes of the present.

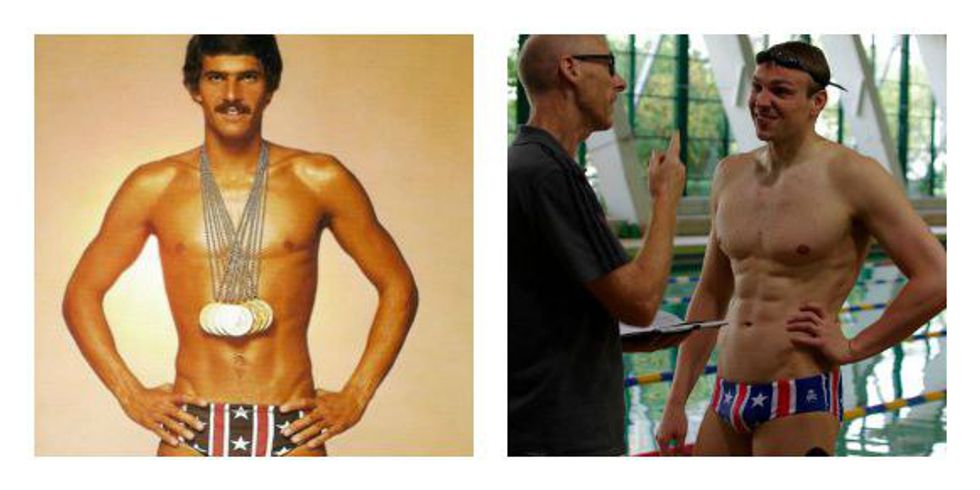

Initially wearing a high-tech-full-body suit when achieving his world record, Paul Biedermann trades his outfit for a 1970s Speedo to compete against nine-time Olympic champion Mark Spitz. During his career, the American swimmer Mark Spitz set 33 official world records and won 9 Olympic golds; a true legend of the past. Unfortunately, without his high-tech suit and the heat of the competition, Biedermann is unable to beat Spitz’ 200m swim record from the 70s. "The suit increases blood flow and overall performance," he says, giving justification behind the banning of the full-body suits in 2010.

Now while most of our technological advances have increased performance, Haake explores the opposite concept in the Javelin event. Old school javelins had the weight distributed further backwards so that they could be thrown further, but officials were concerned that Olympic stadiums would not be long enough for future competitors. Today, the javelin is heavier towards the front to promote a quicker descent. Javelin champion Christina Obergföll picks up an old-school javelin in the documentary to compete against 1980s world record holder Fatima Whitbread. British javelin thrower Fatima Whitbread set a world record that is now unable to be broken due to the different weight distribution used today. Using the old school javelins, Christina Obergföll is able to improve her performance dramatically.

Finally, Canadian kayaker Adam van Koeverden takes up the equalizing challenge, trading his computer-designed carbon fibre kayak for a vintage, wooden model. Koeverden challenges eight-time Olympic medalist of the 1940s, Gert Fredriksson, who dominated kayaking in his time and set multiple world records for Sweden. Unfortunately for Koeverden, Gert Fredriksson’s boat does not include the speedometer and other high-tech capabilities of his usual kayak. Not only that, but the archaic wooden kayak is much the wider, with a less aerodynamic frame than Koeverden's usual slim boat. His new paddles are wooden instead of carbon fibre, also shaped differently so that our athlete is required to change his technique.

In an effort to replicate the notion of competition, Haake decides to try something new by having a cyclist ride next to Koeverden on shore. This gives our athlete an idea of the time that he has to beat, hopefully triggering and heightening his motivation levels. Koeverden is able to beat this time, saying proudly that he thinks he could do even better with practise.