The past ten years, it’s been great to be a Taylor Swift fan. Watching a starry-eyed girl from Pennsylvania skyrocket to success seemingly overnight wasn’t just easy to watch, it was fun to support. Swift has the 5’10 height and the uber-skinny build of a supermodel, yet she shies away from any platform that declares her unreachable and cool. Instead, Swift’s image avidly proclaims her as the underdog, the girl-next-door writing songs about boys that she likes and dreams that she has. The lyrics to her songs read in a diary-like way, and as someone looking up to her, it’s easy to get the message that the feelings young girls have should be deemed valid, not frivolous.

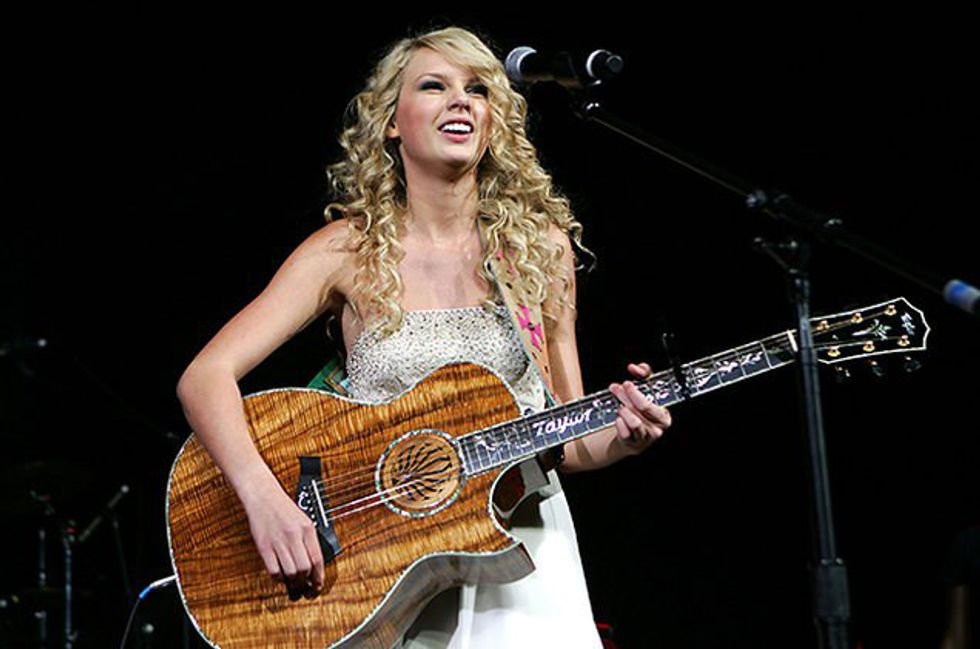

We all know the story of the humble way Swift shot to fame. The instant success of her first album launched her into an unimaginably successful career, generating four headlining tours, ample endorsement deals with the likes of companies including Diet Coke and Cover Girl, and over 150 million albums sold worldwide. Swift’s influence has been proved compelling even beyond the music industry she dominates: last year, she convinced Apple Music to compensate artists through their new streaming service, which was something they initially hadn’t planned to do. With 271 awards under her belt, ten of them Grammys, Swift’s hold on the general population as a public figure and household name is powerful, to say the least. However, as prevalent and up-and-coming Swift has been in the past decade, another phenomenon has held more power than even Swift is capable of: feminism.

What does it mean, exactly, to be a feminist? Feminism is the advocacy of women's rights on the grounds of political, social, and economic equality to men. Or, in simpler words, "feminism" means "equality."

The controversy involving Taylor Swift and feminism goes way back, stemming from Swift's notorious 2008 hit single You Belong With Me. The song chanted, “She wears short skirts/I wear T-shirts/She’s cheer captain and I’m on the bleachers,” (and later includes “She wears high heels/I wear sneakers”) causing a feminist uproar that went over my head when I was younger. The song perfectly described a scenario I imagined any girl could relate to. Swift likes a guy who doesn’t like her back, that likes some prettier, snobbier girl instead. What genius songwriting! Eight-year-old-me thought as I sung the song hundreds of times in front of my mirror with a hairbrush microphone or in the back seat of my mom’s mini van with my friends. My opinion changed as I became familiar with the backlash the song received, which was probably a couple years later.

When the song initially came out, online bloggers were quick to take to the Internet to express their frustration with Swift for the lyrics I was singing over and over. “Giving women a sense of worth based on the type of clothes that they wear is not a good message for Swift’s millions of young fans,” blogger Dodal Stewart wrote in an infamous article titled “Taylor Swift is a Feminist’s Nightmare.” “This takes feminism back 20 years,” read another line. It didn’t help that in the music video for the song, Swift wins over the boy of her dreams in a modest, white gown while her rival wore a tight, bright orange low-cut dress with cutouts.

When I was eight years old, I was quick to defend my idol. Swift was just a teenager, should she really be expected to be as successful as she was in the music industry and take a political standpoint on something like feminism? Her goal wasn’t to be a feminist role model, it was to write good songs. Still, when I was educated on what was wrong with the song, I felt conflicted. The whole idea of the song centers on a virgin/slut dichotomy, celebrating pureness as the epitome of being female.

Another song to cause tension with the feminist community came with the release of Swift’s 2010 album Speak Now, a guitar heavy track titled Better than Revenge.

“She’s not a saint/And she’s not what you think/She’s an actress/She’s better known for the things that she does on the mattress,” was a similar retelling of a virgin/slut conflict with the good girl winning at the shameful expense of a girl who, in Swift’s terms, is not a saint. This was the material selling out arenas? Many wondered. It caused further scrutiny of her work, both from feminists and from myself. When hit after hit came out that just centered on boys, feminists were quick to say things like, "Doesn’t she have anything better to write about? Where are the girl-power anthems? Where are the interviews where she talks about anything other than boys and love?" As faithful of a fan as I was, I couldn’t help but look at Swift’s songs in a new way.

In 2014, Swift claimed to have a feminist awakening… and I say claimed to for a reason. As much as I’d love to believe Swift woke up one day and realized gender inequality was actually a problem, the move came off equally as political as it did scripted. Beyonce and Lorde had delved into the feminist label months before, and received abundant applause for doing so. Swift, not just a musician but a business woman in her own right, appeared to be jumping on the bandwagon of a trend.

She made a point to drop the particular f-bomb in countless interviews, declaring the media perception of her “sexist” and exposing the double standards within male and female songwriters. She created a group of girlfriends that included a variety of Hollywood’s A-listers: Selena Gomez, Ellie Goulding, Hailee Steinfield, Kendall Jenner, and Karlie Kloss, to name a few. This group of supernaturally gorgeous millionaires prompted countless talk on Swift’s part about the beauty of female friendship, and how these girls overlooked standard Hollywood rivalry to build each other up and support one another.

I’m all for women supporting other women, and highlighting the rampant sexism in the music industry, but having an extensive group of girlfriends and pointing out how guys can write countless love songs without it being given a second thought isn’t necessarily feminism. Swift is a white feminist at best, and as you (hopefully) all know, a white feminist is not a feminist at all. (White feminism is just what it sounds like: Supporting feminism strictly for white women, not for all women.)

I am a fan of Swift’s, and I am disheartened to admit that the world dominating pop star I adamantly look up to doesn’t portray the correct definition of what it is to be a feminist. Indeed, my Twitter profile biography used to read “I will unapologetically bring up feminism or Taylor Swift in every conversation, ever.” I didn’t realize the intense contradiction between the two. Now I do.

What’s destructive of Swift’s misinterpretation is that she’s projecting it to millions of people around the world. Swift’s Twitter followers boast over 65 million, and Forbes recently revealed she makes at least 80 million dollars a year. Swift’s talents include songwriting, selling out stadiums, and selling anything in general, really. Reaching to be labeled as a feminist activist as well may be reaching too far. As much as I adore her, Swift has taught me this: Don’t take cues on political movements from pop stars.