The state of education in America is a highly unequal one. Between the de facto segregation of poor students of color versus middle and upper class white students, to the wildly gerrymandered districts that reinforce it, the difference in educational standards for different racial and socioeconomic groups is staggering. But perhaps the most damning evidence of educational inequality are school closings.

Let’s break it down: we’ll say that town A has a public school, and town B, nearby, has a private school. Town A may contain a population that’s mostly poor, black and Latinx. There are only a handful of more privileged families in the area, all of whom go to the private school in town B.

So, unsurprisingly, town A is left with few resources– the area is impoverished already, and school funding is low. Students absorb society’s collective lack of faith in their ability to succeed, and the collective lack of investment in their education– which leads to low test scores, reinforced by limited course selections.

Some disadvantaged students in town A are lucky enough to transfer to a charter school (which themselves are causing controversy). Although charter schools, many of which enroll students based on a lottery-system, may have a higher quality of education than a public school, this by definition leaves some students behind. Although enrolled families may see charters as a great option for those dissatisfied with public schools, this must not be seen as an excuse not to fund public schools at all. After all, if public schools go unfunded with the advent of charters, what happens to the students who don’t “win the [charter] lottery”?

Well, sometimes, their schools close, and students are sent to better-performing districts. Although this can lead to a numerical rise in test scores, it also leads to students, teachers, and parents losing the school that they had come to think of as “home”. Other times, schools simply fall further into disrepair, both physically and academically.

Regardless of ultimate outcome, please see this phenomenon for what it is: purposeful social disadvantaging of marginalized groups via education– that leads to lower college acceptances, lack of social mobility, lack of jobs, and increased rates of things like drugs, crime, and imprisonment.

Now, oftentimes, town A’s students could fairly easily attend another public school, based on geography alone. Indeed, educational gerrymandering has led to minority students having to pass schools geographically closer to them (and whiter, and wealthier) on the way to their dilapidated and under-funded schools. This is not always the case– sometimes, geography is a more accurate indicator of a segregated school district. This has its historical roots in matters like redlining: systematic, purposeful housing segregation of racial and socioeconomic groups.

Well resourced, integrated schools local to the students they serve are the most successful on all counts. They help acquaint students of all backgrounds with other ways of life, boost average income and graduation rates for minority students.They lead to higher rates of other social services being offered at these schools, and higher participation in enrichment programs.

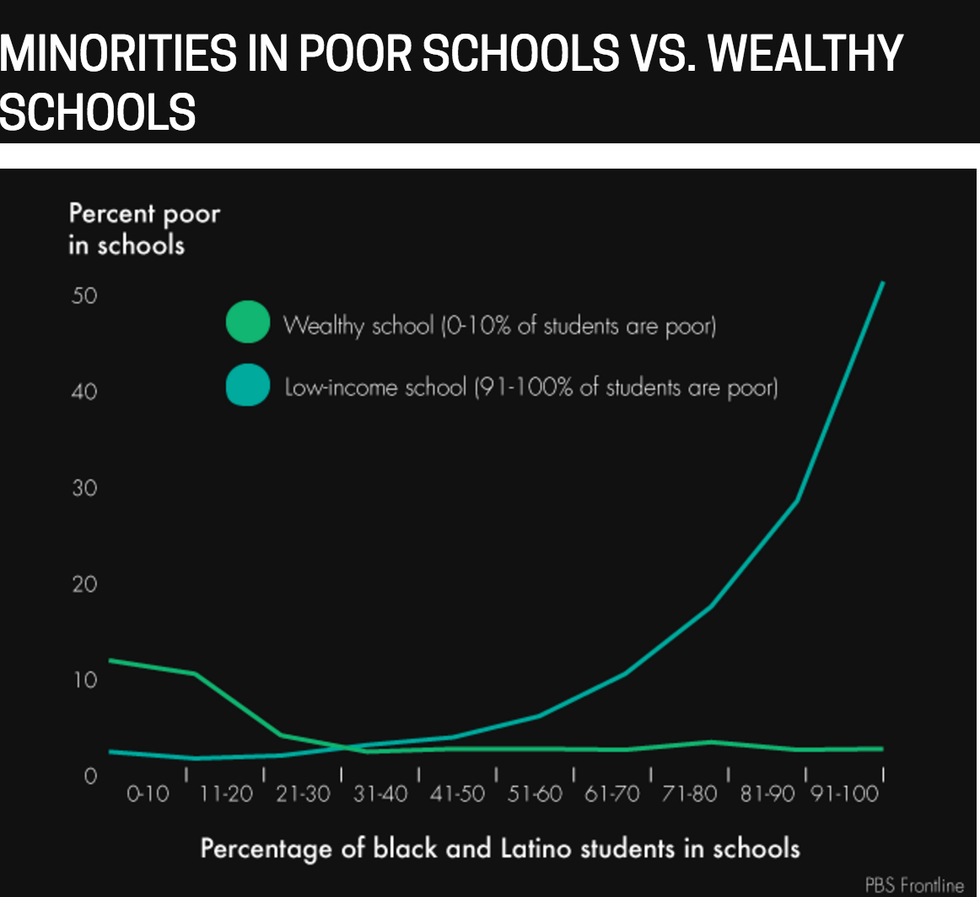

Our world, now more than ever, needs its young people to be as prepared for success as possible. This continued segregation directly carries on the plague of systemic injustice inflicted on poor students of color. To close, here is a graph from PBS Frontline depicting the staggering racial gap in modern day education.

Image description: Graph entitled "Minorities in Poor Schools VS. Wealthy Schools". The graph's Y axis is labeled "Percent in Poor Schools" and its X axis is labeled "Percentage of black and Latino students in schools". Two colored lines reflect the graph's data. The green line is for "Wealthy school[s] (0-10% of students are poor)" and the blue line is for "Low income school[s] (91-100% of students are poor)". Schools that are impoverished tend to have a high (near 100%) black or Latino student population. Meanwhile, the population of black or Latino students in wealthy schools is practically nil.

Injustice comes in many forms, from the obvious to the subtle. Oftentimes, it starts in the classroom–that is, if minority students have a classroom in the first place. In our fight for social justice, we must not forget about educational (in)justice as well.