We need to talk about migration. Political rhetoric has obscured the reality of migration recently and has generally misinformed the public. With the 2016 election focusing on immigration and refugees it is critical to understand the history, current implications, and scale of migration. This will be the first article in a series focused on migration, specifically migration between different countries. I do not intend to force my opinion on you, gentle reader, yet only to clear many myths and misconceptions surrounding the topic. Let us begin with the basics.

What is migration? ‘Migration’ itself does not refer to the movement of immigrants; ‘migration’ only refers to movement and does not require that country lines be crossed. As immigration and emigration both require leaving and entering countries, migration does not equate to immigration/emigration. Migration, though it is not necessarily international by definition, is the word used in this discussion as it includes both immigration and emigration, and does not discount the effects of domestic migration.

Who is a migrant; what is a migrant? There is no singular definition of migrant that is used exclusively, so for this purpose we will adopt the definition used by the United Nations: an individual who has resided in a foreign country for more than one year irrespective of the causes, voluntary or involuntary, and the means, regular or irregular, used to migrate. This definition is intentionally broad; the breadth of people included by this standard provides for the most accurate discussion of migration.

What is the difference between a migrant and a refugee? Migrants can be forced to seek a new country of residency, but often move out of free will. Refugees are forced to flee. As decided by The 1951 Refugee Convention, a refugee is anyone “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.” This definition was agreed upon in post war-Europe; by no means was this standard to be applied to refugees today, nonetheless, this definition is still commonly used to determine who gets refugee status. Until an individual is granted refugee status, they are legally considered an Asylum Seeker. Once awarded refugee status, that individual cannot enter a country illegally.

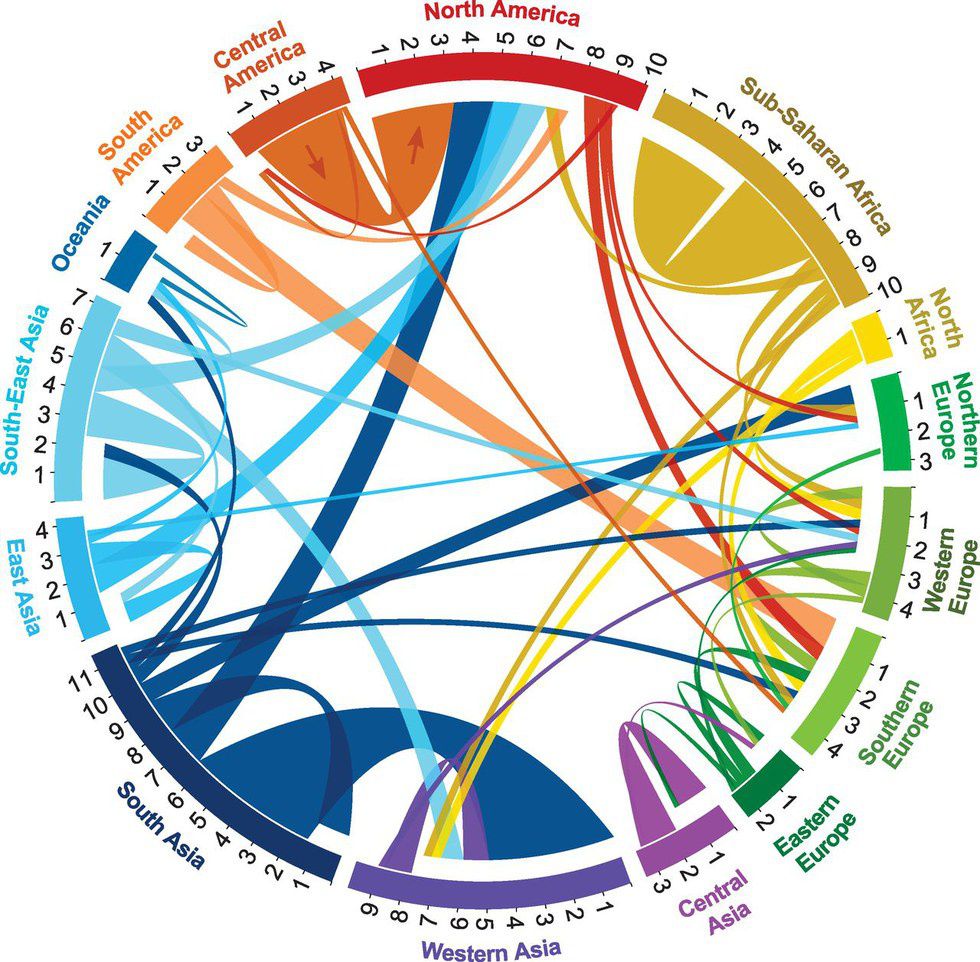

What are Receiving vs. Origin countries? The country that a migrant has left for another is referred to as the origin country, whereas the country that the migrant travels to is referred to as the receiving country. Political discussions today focus exclusively on the receiving countries, yet origin countries experience severe effects.

Why isn’t migration a crisis? Despite almost all of the political rhetoric thrown around today, migration is no more a crisis now than it was 50 years ago. As the population grows, so does the number of migrants, though the percent of the world population that can be classified as a migrant by the definition used above has not risen significantly since the technological developments, and effects of the war, in 1945. Currently, international migrants only account for 3.2 percent out of the entire global population, as of 2013. In 1990, this same percentage was at 2.9 percent, increasing by only .4 percent over 13 years.

Migration is wildly misunderstood, especially given the political rhetoric used in this tumultuous election year. Through this series of articles, I intend to clarify the concept of migration and dissuade common xenophobia misconceptions. In subsequent articles, I will cover theories of why people migrate, types of migration, and why every theory behind migration is false. Until then, challenge the ‘migration crisis.’