Like many leaders and revolutionaries throughout history, Fidel Castro lived long enough to see himself become the villain in many people’s eyes. His death after first coming into power in 1959, has left a complicated legacy for histories to examine. On one hand, he brought healthcare to the Cuban people, eradicated illiteracy, and helped to combat malnutrition in children. On the other hand, he was a dictator who suppressed political opposition and individual rights of the Cubans. A legacy of dictatorship and oppression is especially saddening when studying his entire life. Before thousands of Cubans fled his brutal regime, before he jailed political prisoners, and before he escalated tensions in the Cold War to unprecedented heights, many in America cheered Castro’s revolution on. Fidel Castro had the potential to go down in history as an unequivocal hero, but that chance was squandered by his own doing.

Recommended for you

During his fight against the authoritarian regime of President Fulgencio Batista, Castro promised freedom. In his hour long speeches given to adoring crowds, he did not promise to continue dictatorship on the island. In fact, he promised democracy. After being imprisoned in 1953 for leading a failed attack on a military barrack, Castro was eventually pardoned and released, serving less than two years of his original fifteen year sentence. He traveled out of Cuba to develop his “26th of July Movement.” Returning in 1956 with fellow revolutionaries, they began a guerrilla war against the Batista Regime. This young revolutionary fighting oppression garnered the attention of many in America with the frequent stories of Castro's death in combat, only to find out later that he survived every time. One of his most famous admirers was talk show host Ed Sullivan.

Taking a plane to Cuba and traveling for hours on back roads, Ed Sullivan was able to interview the Cuban Revolutionary as he continued to lead the revolution. Sullivan was known to be a strong anti-communist and asked Castro about whether he sympathized with communists. Wearing a crucifix, he grabbed it and remarked, “‘I’m a Roman Catholic, how could I be a Communist?” Sullivan pushed Castro on his plans for the future government and preventing another oppressive dictator. He responded that, “It will be easy. By not permitting any dictatorships to come to rule our country. You can be sure that Batista is, or will be, the last dictator of Cuba.” Ed Sullivan called him a “fine young man” after he returned to the U.S.

The man who brought America Elvis and the Beatles wasn't the only American media personality to get an interview with Castro. He was interviewed by CBS’s Face the Nation, Jack Paar’s Tonight Show, and later was featured on Edward R. Murrow’s Person to Person. Singer Bob Dylan and author Ernest Hemingway both spoke highly of Fidel Castro and his movement. From the perspective of many in America, he was a hero. Castro had promised to liberate the Cuban people, bring democracy to a people long oppressed, that he was not a communist nor communist sympathizer, and had said that once his revolutionaries were victorious, Castro did not want to lead Cuba. Some even went as far as to consider him a Cuban George Washington.

On New Year's Day in 1959, Batista and many of his supporters fled Cuba. Havana, the nation’s capital, fell into the hands of the rebels. Cuba was now free from the oppressive Batista regime. Castro strong supported moderate lawyer Manuel Urrutia Lleó as provisional president. Most of the new president’s cabinet were sympathizers and members of Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement. He was initially living up to his promise of staying independent from the new Cuban government, but it did not last for long. In February of 1959, he was sworn in as Prime Minister of Cuba. As the new Cuban government began trying and convicting former members of the Batista government, often ending in the death penalty, the American Government became increasingly nervous about Castro. Despite this, the American people continued to be fans of him.

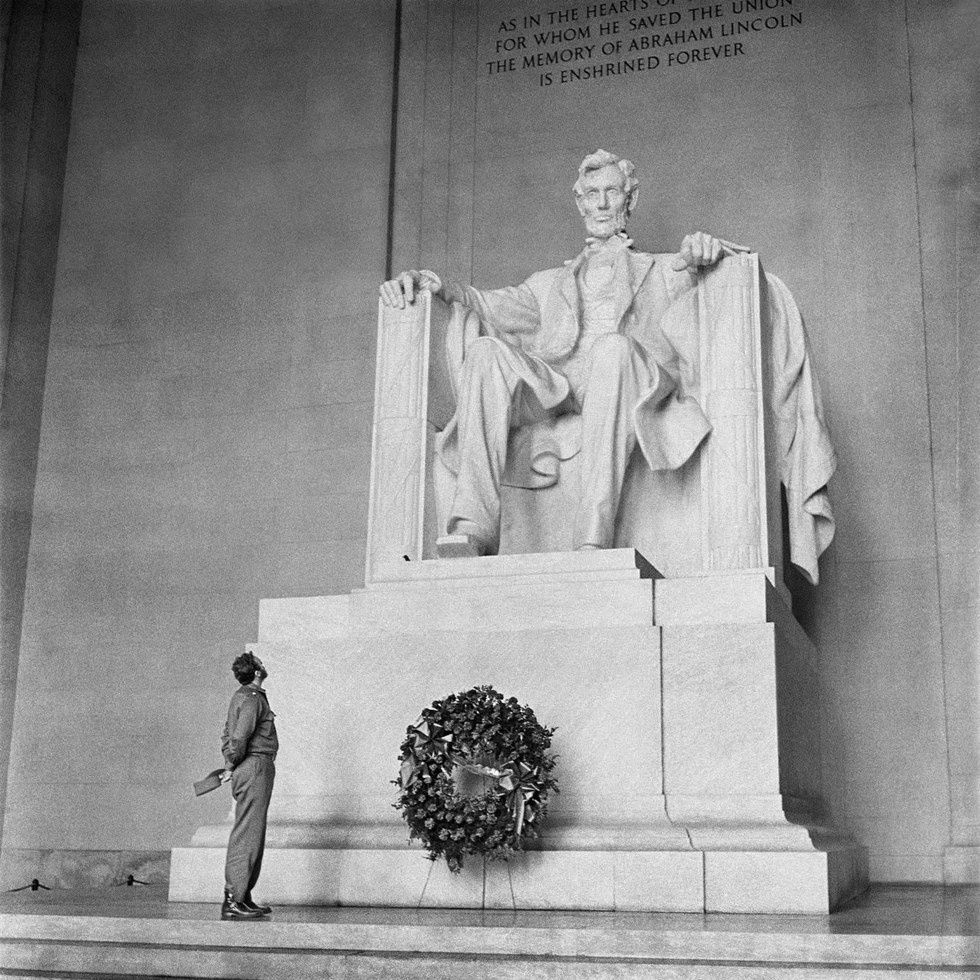

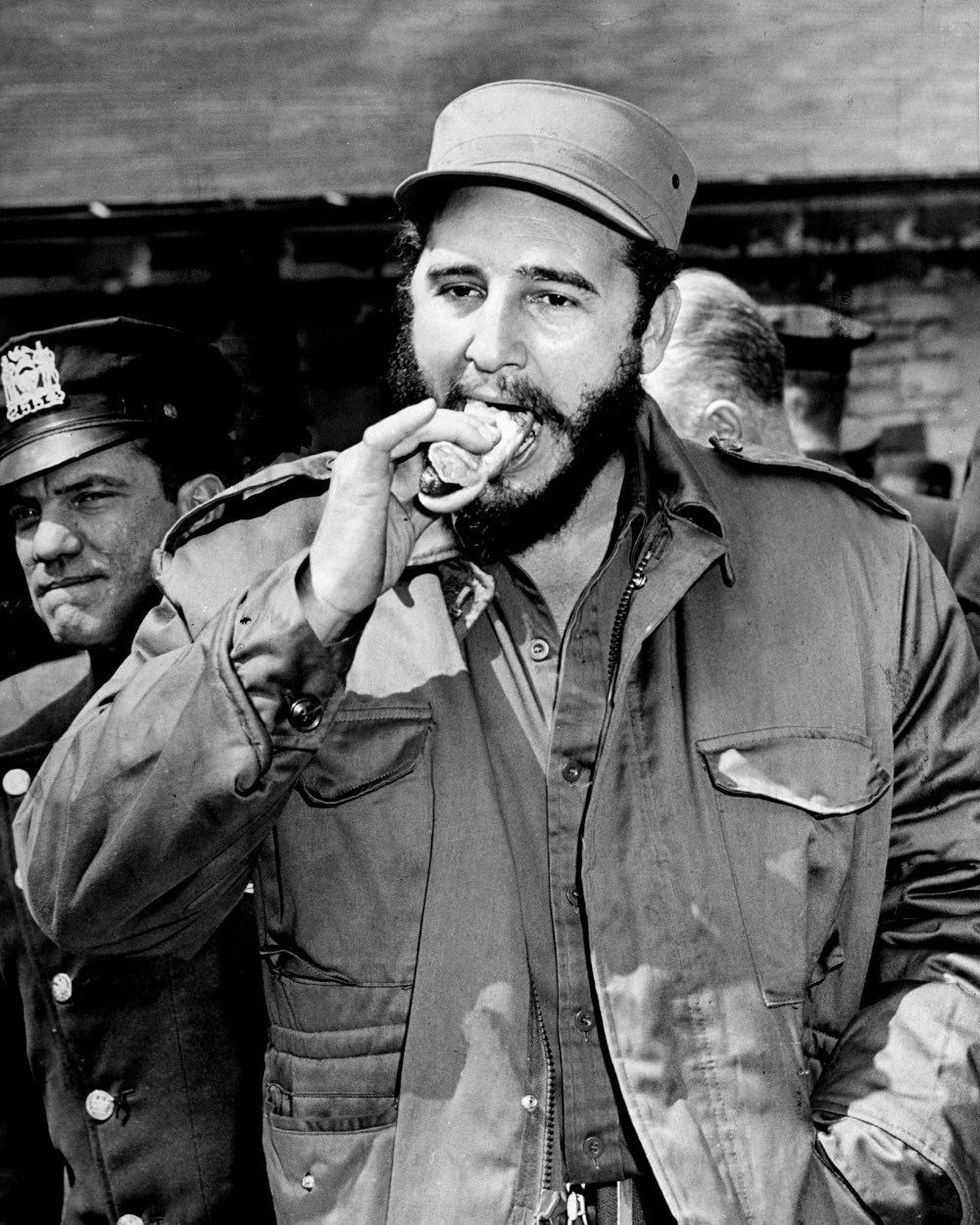

He accepted an invitation from the American Society of Newspaper Editors to visit the United States in April of 1959. He was questioned throughout his visit as to whether or not Cuba’s new government would support communist policies. Castro would answer that, “I am not a communist and neither is the revolutionary movement.” Large crowds gathered to see the thirty three year old revolutionary wherever he went. During his trip, he visited schools, the Bronx Zoo, and did numerous interviews with the press. Castro continued to charm the American people, all the while the government was becoming increasingly suspicious. He laid a wreath on George Washington’s tomb, ate hotdogs at Yankee Stadium, and signed autographs for adoring fans. Although he didn't meet with President Eisenhower, he did meet with Vice President Richard Nixon. Nixon reached the conclusion after their meeting that Fidel Castro was, “either incredibly naive about communism or under communist discipline — my guess is the former.” Former Secretary of State Dean Acheson called him “the first democrat of Latin America” after a meeting between the two. He seemed to have left America as popular as ever with the American public.

After returning to Cuba, relations between the island nation and America began to rapidly deteriorate. Executions continued, Castro was gaining more power, and increased anti-American rhetoric was laced into his speeches. Castro appointed Marxists and other communist sympathizers to government and military positions. He continued a crackdown on dissenting voices within the nation and imprisonment or murder of political opponents. During this time, his government became increasingly friendly with the Soviet Union. Cuba and the USSR eventually agreed to begin trading sugar, fruit, and fibers, in return for oil, fertilizers, industrial goods, and money. As Cuba increasingly sympathized with communist states and after Cuba began to nationalize American owned assets throughout the country, many Americans no longer felt warmly about the Cuban revolutionary.

The rest of Cuban-American relations are familiar to most. Relations between the two countries slowly drifted apart. The Cuban government became increasingly authoritarian as Castro backed away from his initial promises of freedom. The Bay of Pigs Invasion, the declaration of Cuba as a socialist state, Castro coming out as a Marxist-Leninist, and the Cuban Missile Crisis are now the memories Americans have of Castro. His promises of liberation and democracy slowly faded away from the headlines, replaced by the reality of his authoritarian rule and human rights abuses. Bringing the world to the brink of nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis erased from former supporters the fond memories of the Cuban revolutionary.

Castro’s complicated legacy requires a closer look at the events throughout his life. He was not always seen as an evil, authoritarian dictator in the United States. Many believed he was a liberator, a George Washington to Cuba. His actions betray his legacy, much like they betray the people he promised to free from oppression. Fidel Castro’s legacy will include defeating a brutal dictator, improving healthcare for Cubans, eradicating illiteracy, and fighting the influence of the mob, but that is all overshadowed by the fact that he himself because a dictator. History will not remember his promises of freedom, of supporting democracy, and liberating the Cuban people because none of those promises were followed through. Instead, many will remember him only as a tyrant, a dictator, and a murderer. History books do not include pictures of Fidel Castro eating hot dogs in New York City or standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, instead they show thousands of Cubans risking their lives on rickety boats to escape Castro’s regime.