"We, the people of the Democratic Autonomous Regions of Afrin, Jazira and Kobane, a confederation of Kurds, Arabs, Syrics, Arameans, Turkmen, Armenians and Chechens, freely and solemnly declare and establish this Charter.

In pursuit of freedom, justice, dignity and democracy and led by principles of equality and environmental sustainability, the Charter proclaims a new social contract, based upon mutual and peaceful coexistence and understanding between all strands of society. It protects fundamental human rights and liberties and reaffirms the peoples’ right to self-determination." – Constitution of the Rojava Cantons in Syria

If you were asked to name a place in the Middle East where women and men share equal rights, religious freedom is the norm, and people of different ethnicities not only live peaceably but in cooperation, what would you say?

If you answered "Syria," you would be right.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, Kurdish militias have been busy carving out territory along the northern border in pursuit of a revolutionary project based around three liberated enclaves in the cities Afrin, Kobane, and Qamishli. First emerging as independent territories in 2013, these enclaves became known as the three Cantons of Afrin, Kobane, and Jazira, respectively; locals call this region Rojava, and it's home to a budding system known as "democratic confederalism." This system – inspired by the writings of prominent anarchist thinker Murray Bookchin and refined by imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Worker's Party (PKK) Abdullah "Apo" Öcalan – has become the defining ideology of the Kurdish people; it is also an instrumental force in their egalitarian and multi-ethnic tendencies. In fact, true to form, the militias are not only made up of Kurdish fighters, but also Arabs and Muslims, Christians and Yazidis, men and women.

Rojavans administer their territories from the bottom up in a directly democratic manner. This extends from governance of the community to the establishment of local militias. Despite Rojava's war torn surroundings, it's proven a persistent source of equality and cooperation in the Middle East, one that has successfully defended itself from the onslaught of multiple enemies.

"This is a consensus-based, democratic way of life that could become the way forward for Syria, Iraq, Turkey, and Lebanon," Aldar Xalil, a member of the Rojavan Governing Council told the BBC in 2014. "It's a really advanced form of democracy."

Economically, Rojava incorporates communes, worker cooperatives, and even a degree of private enterprise; this last component despite its founders' Marxist-Leninist roots, their eventual abandonment of that philosophy and subsequent embrace of a libertarian socialist model.

Still not intrigued? Check this out: there's no taxesin Rojava. You read that correctly.

Since Rojava controls roughly 60 percent of Syria's oilfields, Rojava's main source of revenue is good ol' Texas Tea, which is sold on the black market. However, agriculture and light industry also make up large sectors of the Rojavan economy. Making matters more difficult, Rojava has often faced significant economic embargoes from neighboring territories, obstructing their ability to effectively trade.

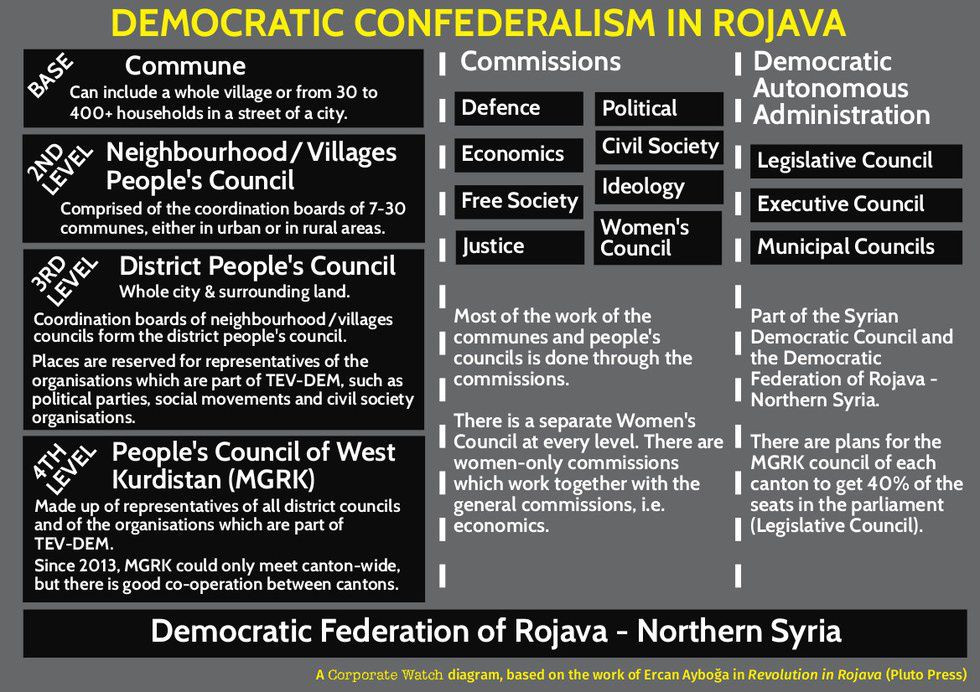

In brief, Rojava's governing bodies are made up of the "commune" at the lowest level, which includes anywhere from a few dozen to a few hundred households. A council is elected by the commune, but the governance of the community more closely resembles the polis of ancient Athens. According to Rojavan constitution, officers elected to a legislative council must be of varying ethnic backgrounds and women must be represented. Separation of church and state is a vital component of democratic confederalism and religious freedom is emphasized.The council's responsibilities include dispute resolution, the provision of public services, economic management, education, and self-defense.

For issues that impact households beyond the purview of a given commune, there are neighborhood or village councils. As the scope of issues expand, matters rise to the elected delegates to the district council and, at the highest level, the council of West Kurdistan. In this way, democratic confederation might appear to resemble representative democracy, but in reality governance is more direct and the individual citizen enjoys significantly more influence than, say, an American does over their federal delegations.

Rojava's administrative bodies differ from conventional republican governments in that elected representatives are immediately recallable by their constituencies, meaning that if they fail to carry out the will of those they represent, a simple majority vote removes them from their post. Wouldn't it be nice to hold Congress accountable in such a way? [For more information on the structure of democratic confederalism see "Democratic Confederalism in Kurdistan" in the continued reading section.]

This revolutionary project has overcome some extraordinary odds. Amidst the Syrian civil war and the encroachment of Daesh (known in Western parlance as ISIS or ISIL,) the people of Rojava have managed to establish and defend a somewhat stable and self-sufficient territory along the lines of democratic rule and equality. Moreover, they've maintained racial and religious cohesion in one of the most sectarian regions of the world. But threats loom large, and not simply from the many jihadists now flocking to destabilized Iraq and Syria.

Turkey has never looked upon the Kurds with great favor. The Turkish state is responsible for imprisoning Öcalan and deeming him a terrorist; he was indeed the leader of a bloody uprising that began in the 1980s and which continues to some degree to this day. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) – a group which traces its roots to Sunni Islamist thought – appears far more comfortable with the likes of Daesh on his borders. As the Rojavan revolution has spread and the cantons have linked up with one another, Erdoğan has threatened military action; this despite the immense effectiveness of the Kurdish militias against the Islamic State. It is worth noting that Turkey is a NATO ally, and yet their actions – leaving gaps in the border that maintain major ISIS supply lines, provoking Russia in petty border disputes – seem to benefit jihadists more than any other faction. Meanwhile, Erdoğan has cracked down on Kurdish rebels at home.

This has forced the U.S. to walk a fine line. On one hand, the Americans are supporting the Kurds, recognizing their invaluable contributions against the Islamic State. On the other, Washington is eager to pacify a NATO ally that seems intent on wiping fledgling Kurdistan off the map before it can develop. How these geopolitical considerations evolve will be instrumental in determining the future of the Rojavan revolution.

For now, though, Rojava represents a bright spot in the Middle East and a banner of hope for the rest of us preoccupied with finding alternative ways forward. If these resilient people in northern Syria can band together to create something worth fighting for in the middle of a warzone, than those of us in more stable regions of the world could certainly overcome our own challenges. All it takes is the will to organize and implement creative ideas. So why wait for a civil war when we have the resources available to us now?

*Any errors or oversights included in this article are the author's own. Corrections and criticisms are welcome in the spirit of advancing academic thought and critical understanding of human social organizations.*

This week's musical guest is Rezan, a Kurdish rapper I came across in the process of researching this article. Enjoy.

Continued reading:

"Democratic Confederalism in Kurdistan" by Tom Anderson and Eliza Egret

"Our Attitude Toward Rojava Should be One of Critical Solidarity" by Zaher Baher

"Rojavan Cantons Connected After Major Kurdish Victory" by Yvo Fitzherbert

"The Rojavan Revolution" by Evangelos Aretaios

"Abdullah Öcalan, Kurdish Militant Leader" by Richard McHugh