Many of you are probably familiar with the feeling of being sunburned, at least a minor one at some point in your lives. I am particularly familiar since I have been in Florida for the past week.

Before heading to the beach, I put on my 100 SPF sunscreen as usual and reapplied every two hours, confident in my protection from the brutal sun. After all, 100 SPF sunscreen is about the highest one can get and even my skin (absolutely pale from spending all my time in the biochemistry lab) should be adequately prepared for any scary ultraviolet rays, right?

Wrong.

I burned the first day. Badly.

Obviously, it hurt. The title of this article is very accurate as to the pain level and inability to move without feeling like I was leaving lots of skin behind. To distract myself from the pain, I focused on understanding how so much damage occurred in such a short amount of time, even with all the care I took in skin preparation.

For starters, I looked up how the sun affects the skin. Apparently, the light from the sun that we see is not all the light emitted, and the invisible ultraviolet light is the scary part. Here is a nice visual of what this terrifying invisible light would look like if it were visible... which, again, it is not.

The UV light is quite intense, carrying much more energy that the light in the visible spectrum. When this light hits the skin, DNA in skin cells becomes damaged and this causes mutation. The most common mutation is in one of the four DNA nucleotides: thymine, causing thymine dimers, shown helpfully here. Basically, they fuse together, preventing the DNA from being properly copied.

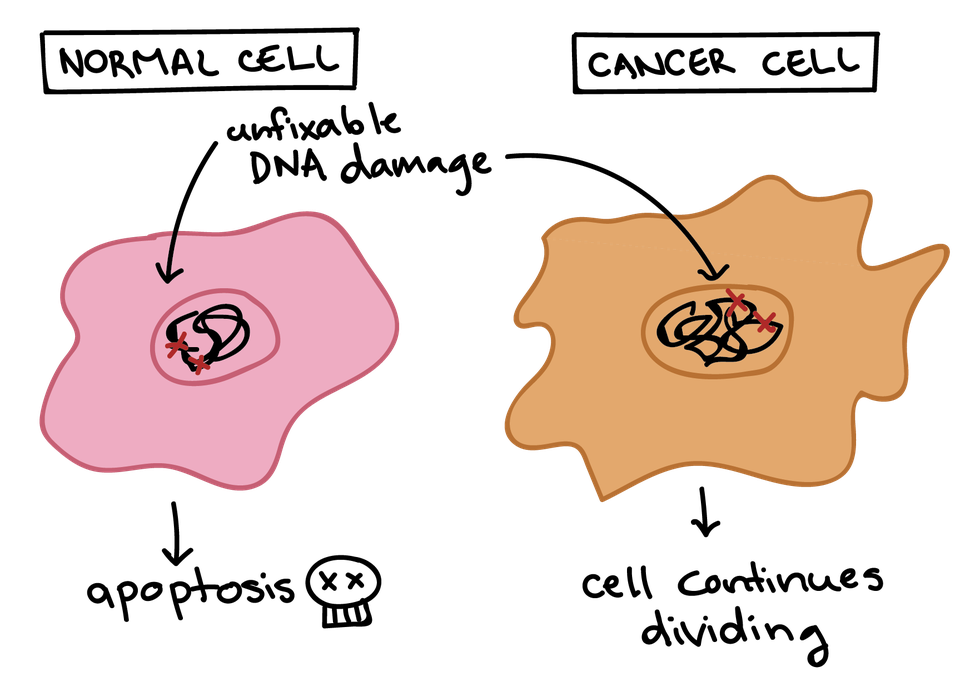

As the DNA is messed up and the cell does not want to propagate these mutations, it makes a decision to go through apoptosis, which is the process of voluntary cell death. This cell damage and death are the root cause of the sunburn.

As these cells die, the body begins sending blood to the area to assist in damage control. Inflammation begins, bringing with it the terrible pain and redness and heat. This is what makes it feel like someone is ripping your skin off and it's your body doing it to you for your own good. Blisters can form as well as the body wants to pad the area with fluid bubbles. Later on, skin peeling occurs as the dead cells slough off in the most unpleasant manner imaginable. Here is a nicer image so you don’t have to see the horror show.

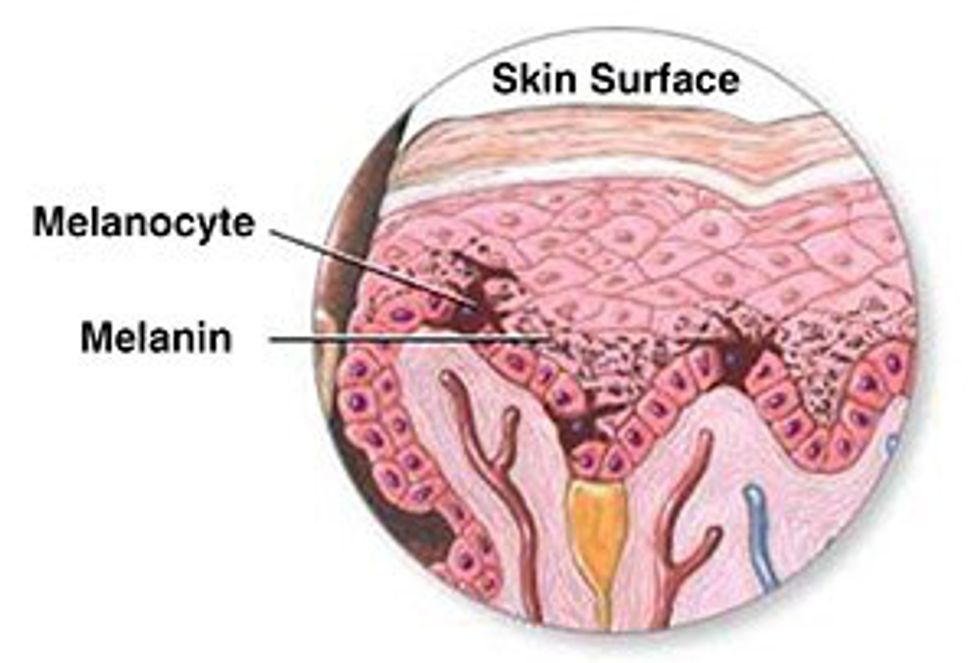

The presence of melanin (a pigment in the skin) can protect the skin by absorbing ultraviolet light from the sun and dissipating the energy as heat. When the skin feels damage from the sun, special cells called melanocytes begin producing more melanin to try to prevent a sunburn. Most people have around the same number of melanocytes, but the amount of melanin varies and the color of the melanin varies. Those with more melanin are less prone to burns, but even those with significant amounts of melanin are vulnerable to some damage and a tan does not necessarily protect you either.

If the cells damaged by the sun fail to go through apoptosis and somehow survive, mutations can cause the inability for these cells to stop growing. That is when serious stuff like cancer becomes likely. Cancerous cells are functionally immortal and just keep growing and growing and starving other healthy cells.

So obviously sunburns are potentially extremely unhealthy and definitely extremely unpleasant. How can sunburns be avoided? Does sunscreen really work to prevent these problems?

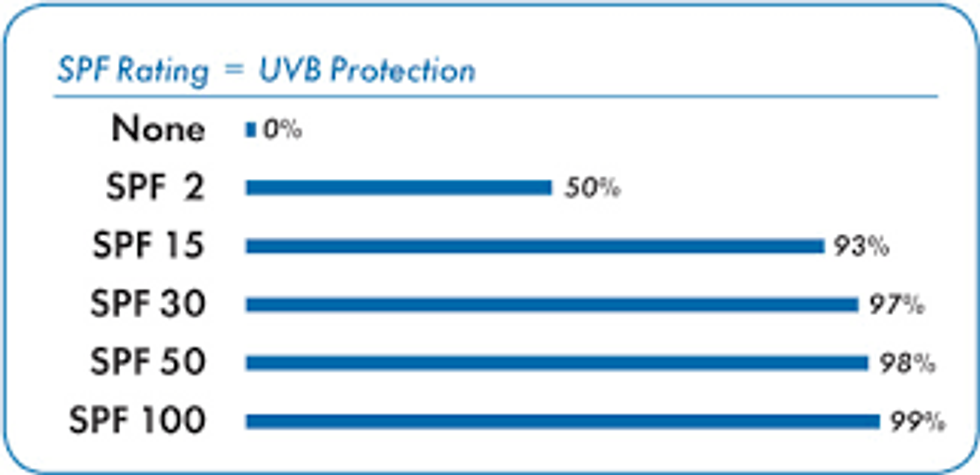

Sunscreens basically work by reflecting ultraviolet radiation, redirecting it so that it cannot damage the skin. Ingredients like zinc oxide and titanium dioxide are key in this process. SPF, or sun protection factor, supposedly amplifies the amount of time one can spend in the sun before burning. Someone who can spend 10 minutes outside before damage occurs wearing an SPF 30 sunscreen would theoretically have 300 minutes before a burn occurs. This is obviously only an estimate and does not factor in things like how much sunscreen was applied, how direct the sun’s rays are, and how much sunscreen could have been washed or rubbed off. Another factor is that the scale is not linear.

As you can see, an SPF 15 sunscreen theoretically blocks 93% of the damaging UV rays while SPF 30 blocks 97% and SPF 50 blocks 98% of the rays. Obviously, 100% cannot be blocked, so increasing to SPF 100 does not really do all that much more.

So basically, I did what I was supposed to do by putting on sunscreen, but my confidence in the 100 SPF sunscreen was misplaced. My skin is simply not prepared to deal with the destructive power of the sun for any long period of time. The good news is, the fact that I have a sunburn means that cells are dying, which is good because those cells can’t become cancer. I guess my conclusion is, therefore, that (after spending so long outside) having an awful sunburn is a lot better than the alternatives.

sunrise

StableDiffusion

sunrise

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion