It is very often that if you walk into a jam-packed university library during finals week you’ll encounter desperate students cramming six weeks worth of homework into an all-nighter or stressing out about memorizing all thirty chapters of a book for an exam in the morning. Evidently those seem (and quite frankly are) very unrealistic goals which not only are the consequences of poor schedule planning but also very unhealthy habits that make it seem as if one who could pull off such a feat must have some sort of superhuman set of skills. To college students everywhere those “superpowers” are readily available and come in the shape of little round pills known as “study drugs”, “brain dope”, and “academic steroids” which, to the average neurotypical student is that extra “boost” they need to finish their 15-page paper, three projects and even study for an exam all in the same day. However, to students who actually possess Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), the so-called study drugs are the medication they need to put them in the same level as everyone else, however, those who don’t exactly need them end up excelling above their normal academic capacities and posing ethical questions when it comes to “academic steroids”.

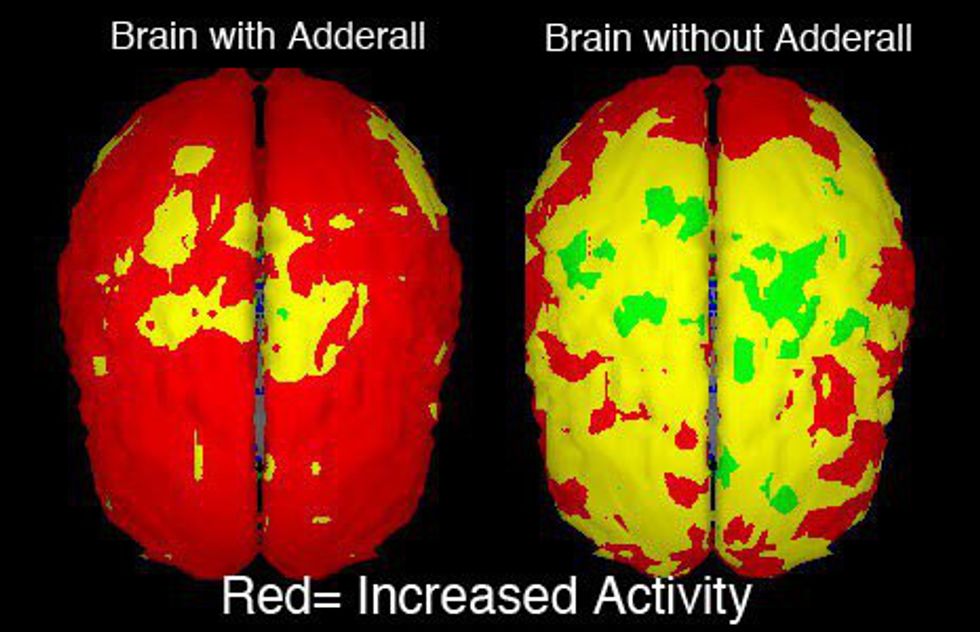

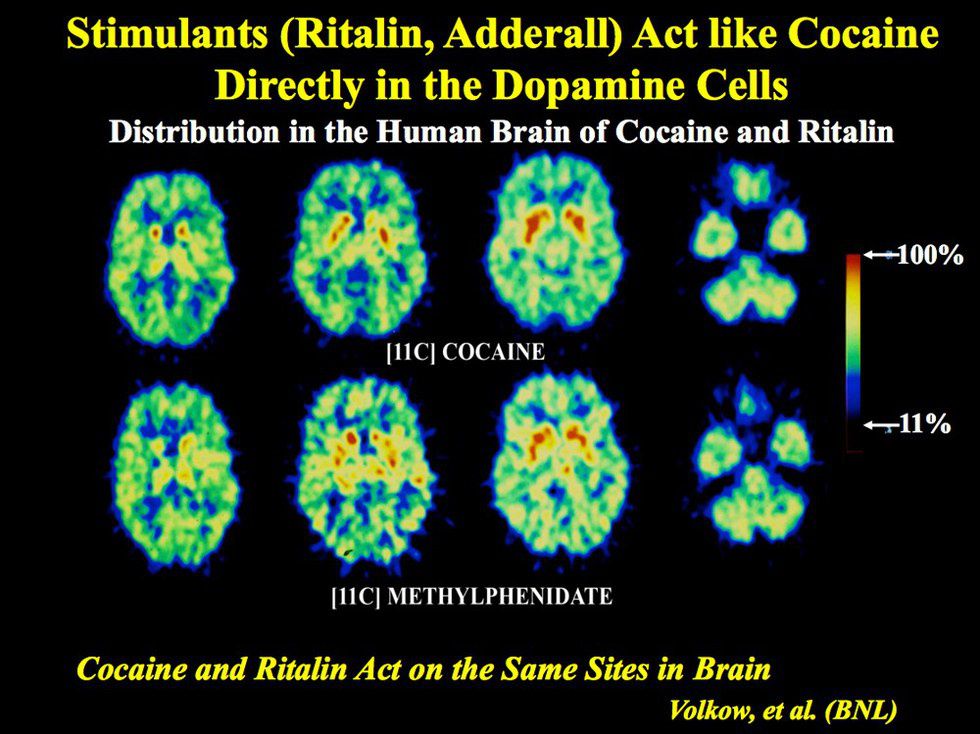

Increased alertness, brain capacity, focus and clarity are just some of the “positive” effects of study drugs such as Adderall, Ritalin, Concerta, Vyvanse, and Focalin on “healthy” brains. What all of these drugs have in common is that they’re mainly composed of amphetamines, besides other stimulating chemicals. Amphetamines over-stimulate the neurotransmitters responsible for producing adrenaline, dopamine and norepinephrine as it mimics the actions these neurotransmitters already perform, yet to a much higher degree. Epinephrine, or adrenaline, acts on the sympathetic nervous system that controls our fight-or-flight response and induces more alertness, focus and clarity; while dopamine brings in feelings of pleasure and accomplishment. Norepinephrine then wraps it all up by controlling all the previous activities as it expedites the communication between the neurons, making them last longer. However, the list doesn’t end there - other drugs such as Modafinil, Adrafinil, and Phenylpiracetam have been in high demand around college campuses and used for studying as well, however these drugs aren’t stimulants but rather categorized as nootropics. Nootropics are classified as substances that enhance cognition and memory as well as facilitate learning as they increase blood flow to the brain, thus boosting neurotransmitter activity and are often used to medicate patients who suffer from narcolepsy - such is the case with Modafinil.

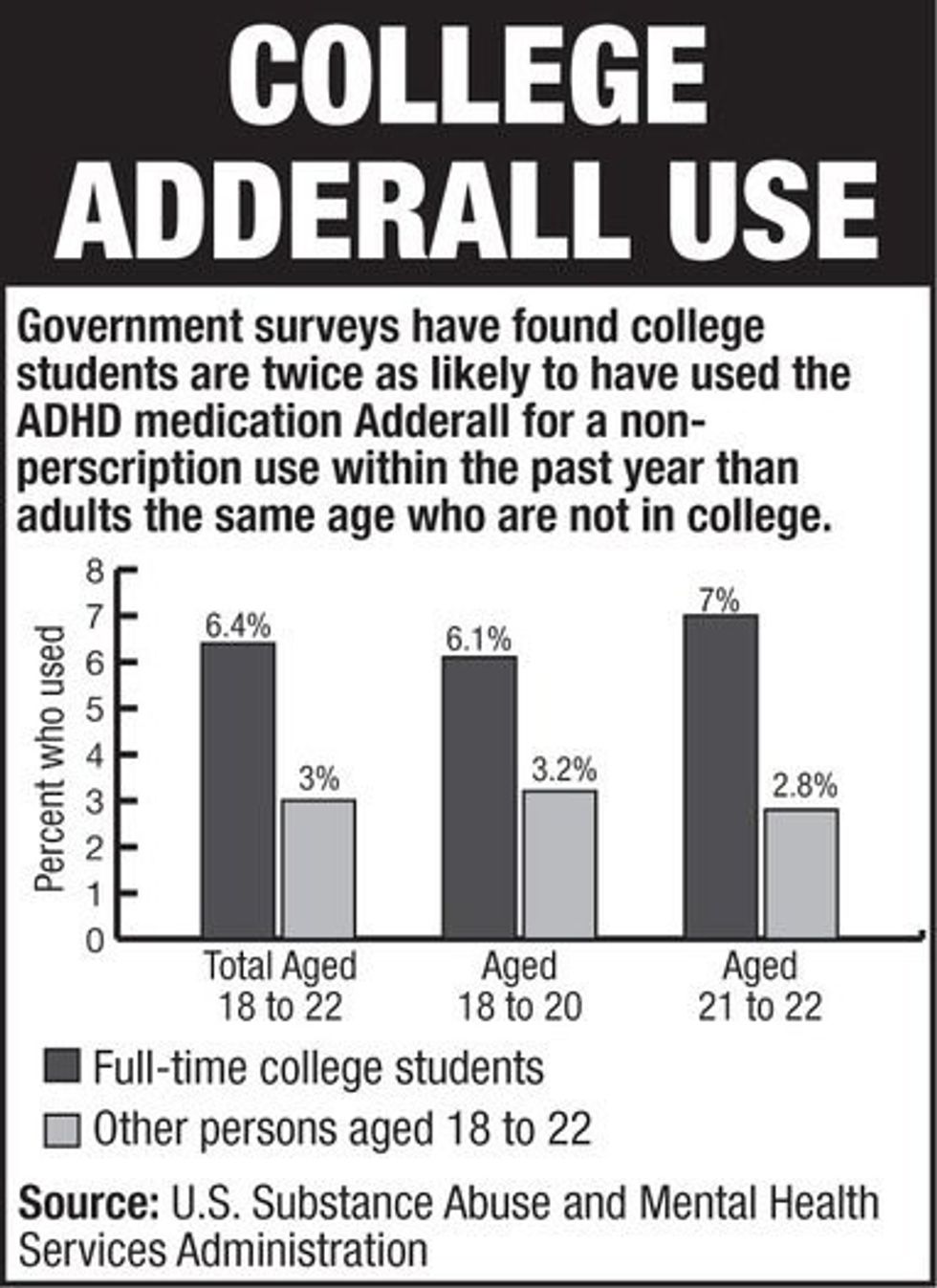

Recent studies have shown an exponential increase in the non-medical usage of prescription medication for attention disorders as stimulants within students in American college campuses to get ahead academically. The rapid surge of misuses of amphetamines and nootropics reveals that the problem is still not taken as seriously as other drug concerns around universities for several reasons, the leading factor being that it is, for the most part, used for academic purposes, seeing as more than 90% of users take them solely to focus on schoolwork. However, these drugs are classified as schedule II substances, placing them right next in line to cocaine, methamphetamines and morphine, substances which the DEA classifies as having a high potential for abuse. Statistically, full-time college students ranging from ages 18 to 22 were two times more likely to take prescription study drugs non-medically and out of those who were non-medical users of Adderall or other amphetamines almost three times as many were inclined to have used marijuana in the past year, eight times more likely to have used cocaine and prescription tranquilizers and five times more likely to have used prescription painkillers within the same time period.

The key element that most students seem to ignore regarding study drugs is that the access to them for non-prescribed persons is illegal for a reason, seeing as even though these are controlled substances there are still implications such as the stimulant's documented contraindications (instances where a drug may be harmful), the recommended precautions and dosages and how it may interfere with other drugs, such as antidepressants. That being said, however, students often rationalize using study drugs because it benefits them academically, which make it excusable as long as they get their work done and complete assignments. Another important factor that makes study drugs seem safe is the facility with which students can obtaining them. The underlying fact is that street drugs get a bad reputation for being held under shady transactions and usually referenced in more hardcore and severe accounts of addiction, whereas prescription pills are distributed in hospitals and medical centers where a false illusion of control is established as it seems that, even though these are drugs, they are “safe”. Yet, as aforementioned, these substances have a higher potential for abuse and addiction and if dosed incorrectly could lead to rather perilous consequences.

Studies have shown that the demographic of college students who misuse stimulants for academic purposes varies significantly by school, however, the greatest portion of users are concentrated in elite and private universities. A study presented at the annual Pediatrics Academics Societies in 2014 revealed that one in five students at an Ivy League college misuses stimulants in order to get ahead academically, which is twice as much as the rate of the abuse of “academic steroids” within a larger scope of colleges. The study, conducted anonymously with 616 students who have not been diagnosed with ADD or ADHD yet misused stimulants revealed that 18 percent admitted to misusing study drugs at least once in their college career while 24 percent admitted to doing so on eight or more occasions. Out of those surveyed students, 33 percent don't see it as cheating, while 41 percent does and 25 percent were unsure, which raises ethical concerns around the idea of these drugs not only being an unfair advantage but also treated with such a sense of normalcy. According to the principal investigator of this study, Natalie Colaneri, a research assistant at Cohen Children's Medical Center, “it is important that this issue be approached from an interdisciplinary perspective: as an issue relevant to the practice of medicine, to higher education and to ethics in modern-day society."

Anjan Chatterjee, a neurologist at the University of Pennsylvania coined, in 2004, the term “cosmetic neurology”, which refers to the usage of known controlled substances that would normally be used to treat recognized medical conditions to strengthen ordinary cognition. He worries the concept of cosmetic neurology will become as normalized as cosmetic surgery, where those who aim for the advantage will continue taking the pills and intimidating those who don’t into not wanting to fall behind and eventually caving in. “Many sectors of society have winner-take-all conditions in which small advantages produce disproportionate rewards,” Chatterjee notes in one of his papers. For Chatterjee, the underlying issue is that the demand for neuroenhancers only tends to grow as it doesn’t affect just one demographic but rather the entire scope of those eager to produce more, at a faster rate and retain more information. However, overall neuroenhancers have proven to be most requested and used within college campuses, seeing as students who have to juggle their school workload, a social life, work, involvement with the school, managing life on their own and a healthy lifestyle feel the need for an extra boost in order to manage it all.

Obtaining study drugs would have been relatively hard if you were a student at a small school in the middle of Maryland with a very limited circle of friends about thirty years ago, yet today it is with a click of a button that you can purchase any and all of the cognitive enhancers the market has to offer. The convenience with which these drugs can be obtained makes it so there are even online forums set up by people so fascinated with the concept of tweaking their cognitive functions to discuss the usage and obtainment of nootropics and amphetamines which anyone can access. One man who found himself stuck in an ethical dilemma regarding a co-worker and their usage of neuroenhancers when said worker was “using unprescribed modafinil to work crazy hours […] our boss has started getting on my case for not being as productive.” Such an issue leads us to question the disadvantage that puts people, both neurotypical and neurodivergent, since there are people who will gladly do their work without feeling the need to take any sort of “enhancer” just to get ahead.

Even though the common usage of study drugs amongst non-medicated students is not a recent trend, there is still a good amount of people unaware of its adverse side effects. Surely those who partake in them are fully aware of the highly addictive properties of the drug and how the short-term side effects might not be ideal, however, most of them don’t know that the excess dopamine in their system which causes momentary euphoria and restlessness can lead to depression and exhaustion once the drug wears off. The bottom line is that neuroenhancers are a quick fix to something most people could take care of by simply getting a better night’s sleep, eating properly and exercising regularly; however a small blue pill sounds a thousand times more appealing than practicing Sudoku and eating your veggies.