This semester I decided to take a class on a subject that has always interested me: the Holocaust. I've learned so much about racial tension and immigration, both past and present, but a truly special part of the class was when I had the opportunity to meet with a survivor.

Pittsburgh's neighborhood of Squirrel Hill has a large Jewish population, and most survivors in the city live there as well. Classmates and I traveled to a Squirrel Hill apartment complex to meet Moshe Baran, a 96 year-old man who escaped Poland and became a resistance fighter in the forests.

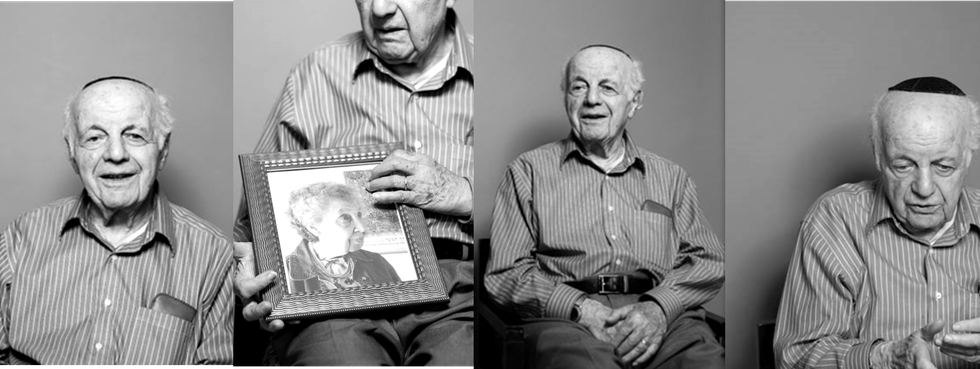

A small old man came into the meeting room with the help of his walker. He turned around into a seat connected to his walker, looked up at the twenty of us and said "So, what do you want to know!"

Moshe grew up in Horodok, a small Polish village on the Russian Border. The Russians (who originally sided with Nazi Germany) invaded his town in September of 1939. Moshe recalls that, in going from a democracy to Russia's authoritarian rule, the townspeople could only get censored information of the outside world from one government-controlled radio station. In 1941, the Germans invaded Poland from the other side, and within a few weeks, 300 Jewish families from his town were deported to a ghetto of just 15 homes.

Luckily, being young and strong, Moshe and a few friends were sent to a nearby railroad station to work. Every german at the railroad station was very mean toward them except one, Lt. Miller. Moshe and his friends quickly noticed that every town around them was being liquidated and realized they had to escape. They wanted to join the resistance, groups of Jews and non-Jews who hid in the forests of Eastern Europe and planned attacks against Germans. The only problem was that a person needed a weapon to be accepted into the group. How on earth was a Jew supposed to obtain a gun?

Moshe's two friends worked in a factory near the railroad, sorting abandoned weapons. Every day they smuggled out a gun part in a rag and tossed them in the junk pile during work. At the end of the day, Moshe convinced the nice Lt. Miller to let them each take something home from the junk pile. Of course, they took the gun parts and assembled the weapons outside of the station.

The next problem was that a fence surrounded the station, and the forest camp of the resistance was twenty miles away. One night, the men dug a hole under the fence and slipped out the station, making it to the forest camp in time for the sunrise. Moshe notes that he saw the sun for the first time since German occupation; until then, everyone had only looked down.

A few weeks later, two Jewish Russian officers walked past the forest camp and wanted to help plan sabotage against the Germans. (By this point in the war, Russia had changed sides and was now against the Germans.) Moshe told the men he wanted to fight with the partisans, an elite group of resistance fighters. The Russians told him to contact a farmer named Kowarski.

By this point (1942), Moshe’s hometown was destroyed and his family went into hiding underground. Farmer Kowarski brought the family, as well as more weapons, to Moshe in the forest. The partisans then accepted Moshe into their group, but his friends were killed before they could also become partisans. While his family stayed in a safe Jewish camp for the remainder of the war, Moshe was trusted with a special mission: find clear spots in the forest and build fires to signal the location where allied planes should drop weapons. Once dropped, Moshe had to retrieve them for the partisans.

The locals had good intelligence and told the partisans what nearby German divisions were up to. They were able to avoid face to face combat with the enemy as a result. By the spring of 1944, Germans were retreating from the area. The partisans followed Germany’s trail, moving through swamps for 10 days before getting close to the front lines. Moshe remembers hugging trees as a way to sleep while treading in the swamp. Some people even slept while they walked.

After the Germans had been pushed back from eastern Europe, the partisans’ task was over. Moshe slept for 48 hours straight. His hometown had been burned to the ground by Russians, who had suspected Nazi collaborators of hiding there. Only the synagogue remained. Moshe moved from the forest into a neighboring town, where he got a job as an accountant. Now living in part of Russia, Moshe was called into the Russian army. His knowledge of accounting allowed him to do office work instead of fighting on the front lines.

When the war was over, Moshe went to a displaced persons (DP) camp in Linz, Austria. These DP camps were set up all over Europe for Jews who didn’t have family or a home to go back to. In this camp, he met his future wife, Malka, also a survivor. The two came to the U.S. from Austria in 1950.

Moshe noted that his mother was the only mom from his hometown to survive. Moshe was also the only survivor from his hometown who was able to save some of his family members - his sister is still living and also resides Pittsburgh.

I have listened to a couple of Holocaust survivors before, but those cases were more like lectures than intimate discussions. I was amazed at how easily he spoke. He didn’t seem angry or bitter, but rather he radiated hope and belief in the goodness of humanity. He told us that his wife refused to use the word “hate”, even to describe the Germans who made her life Hell on earth. As someone with a long history of mental health issues, I still get emotional when telling people about the hardest things I went through. His situation was so much worse than anything I ever had to deal with, and yet he was able to so openly and calmly tell his story and answer any questions we had. No questions were off limits.

Another thing that struck me was that his survival rested on so much random luck. From the weapon smuggling, to the farmer (oh yeah, did I mention that Farmer Kowarski was a double agent?!?! Moshe suspects he was a part of the German military, for that was the only way he would have been able to 1) locate Moshe’s family in the ghetto and 2) get Moshe so many guns. And strangely, when the Germans disappeared from the area, so did Kowarski. For some reason we’ll never know, Kowarski decided to help Moshe and his family. He never threatened to harm Moshe or asked for anything in return.

When I was in Austria this summer, I visited Mauthausen concentration camp, which is right outside of Linz. Additionally, one of the girls we met while studying abroad was from Linz, so it was nice to have a personal connection to Moshe’s story.

Moshe’s wife, Malka, passed away seven years ago, but she was just as forthcoming about her own stories. She liked to write about her experiences to relieve some of the burden. Their two daughters knew a lot about what happened to their parents, and Moshe even traveled with one of his daughters back to his hometown in the past decade. I don’t know if I would have the strength to return to a place with such horrible memories.

Moshe is one of the more well-known Holocaust survivors in the Pittsburgh area. He often speaks at events, was featured in the news and even starred in a documentary made by a student from Allderdice High School.

*I asked Moshe why he chooses to continually tell his story when so many have decided to never bring up their experiences or even tell their children. He immediately responded: “If I don’t who will? How will you learn about what happened?” I think that is such an inspiring message, especially to a growing generation of young people who couldn’t care less about learning history. I am so grateful to have had the opportunity to talk with Moshe, and it makes me sad that the world will soon lose a population with such amazing stories.

Additional readings on Moshe:

http://holocaustcenterpgh.org.

-http://jewishpartisans.blogspot.com

-