Food is undeniably one of the most important aspects to any culture; students who have traveled far from home to attend school in another state may constantly talk about how much they miss their parents’ food.

Your grow up on your favorite cultural dishes; food then becomes part of your memory. It can bring people together as a community and connect families. Food is what people get excited about during the holidays; mothers, fathers, sisters, uncles, and aunts come together to prepare a gigantic meal for everyone to share. It’s when loved ones get to cook their favorite dishes for people to fill themselves with and enjoy.

I have many distinct memories of my mother cooking a typical, traditional Chinese meal for me and my siblings. Among the delicious (Chinese sausage), steamed bok choy, and salty eggs, white rice was always, always, always abundantly available. I remember coming home from kindergarten and helping my grandmother wash rice and prepare it in the rice cooker a few hours before my mother came to cook the accompanying flavorful foods. My grandmother used to explain to me that the white rice helped to enhance the flavor of its accompaniments, which I can now completely understand because I can make a simple, filling meal out of leftover sauce from any meaty meals on rice. Eating white rice with my family always filed me up with joy and gratitude because my mother always reminded me how lucky me and my two siblings were to have enough rice for all of us to indulge; it brings me back to the happier and simpler times.

So what could possibly shake such a close connection to my mother’s food?

At some point in high school, I was bombarded with pamphlets that told me I should “eat this, not that.” Some listed out the difference between whole grains and white grains, and among them most striking to me, was the difference between brown rice and white rice. Much of the information basically went along the lines of how white rice has close to no nutritional value versus its super-food, healthier counterpart. There was a bunch of other scientific jargon squeezed in there as well that my adolescent mind skipped over, but the message was clear: someone was telling me my mother’s white rice was an unhealthy option.

At first, I was a bit shocked – I always considered my mother’s meals to be very healthy; she always loaded our plates with vegetables and some protein for a balanced meal. She never introduced brown rice to us, mainly because it wasn’t available in the Chinese supermarkets she went to, or it wasn’t available in the massive 20- or 40-lb bags that holds the white rice. At Chinese restaurants, brown rice just wasn’t an option because that’s just not how the dishes are traditionally done.

I admit, I let myself be affected by the information I was hearing; I wanted to make some changes in my diet to be healthier at a time where I was so receptive to everything I was seeing in the media. For a short time, I started taking my dinners without white rice, and I saw the effects it had on my mother –- she was offended I wouldn’t eat her food and kept asking why. I didn’t have the words to explain to her that I was influenced by some outside source to not enjoy the food she put in front of me, and in retrospect, it makes me angry that I let all of that buzz and nutrition craze that has dominated this generation get to me.

I thought long and hard about what I was doing, and I started to unpack what was happening.

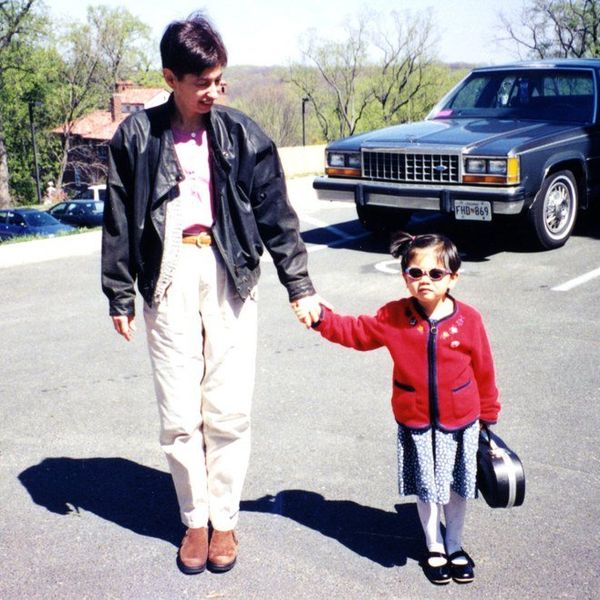

Like I’ve mentioned previously, my mother’s food has always been important to me, ever since I could remember. She taught me Cantonese as she fed me, and always spoke to me in this beautiful language in hopes of teaching me to become fluent. However, going to kindergarten made me exclusively speak English at school, and naturally that made its way into my home. I could never notice, but I was slowly losing my ability to speak Cantonese and I could see it hurting my mother. But she still continued to cook her food as she did, keeping this bridge between us to keep us connected, her love emanating through every pot of rice and every meal she prepared for me.

I realize now that loving my mother’s food is a resistance to that message of what should and should not be or do as described by some authority that has sought to erase the things that keep me connected to my culture. I’ve already felt that I’ve spent so much of my life losing my native tongue that I want to stop continuously losing the parts that keep me connected to my mother.

Stop citing “science” as the authority of what I should and should not eat. Science and biology have born theories that brainwash people into oppressing others because of some inherent inferiority/superiority relationship. Science won’t tell me how to love my mother’s food as an act of resistance every day, something I am adamant about standing strong for.

Food is resistance. Stop telling me my mom’s white rice is unhealthy; I’ve already lost a great deal of my ability to speak Cantonese fluently, without inserting English words in my sentences, because I have been bred to only speak English outside of the home. Stop trying to erase these precious parts of me.