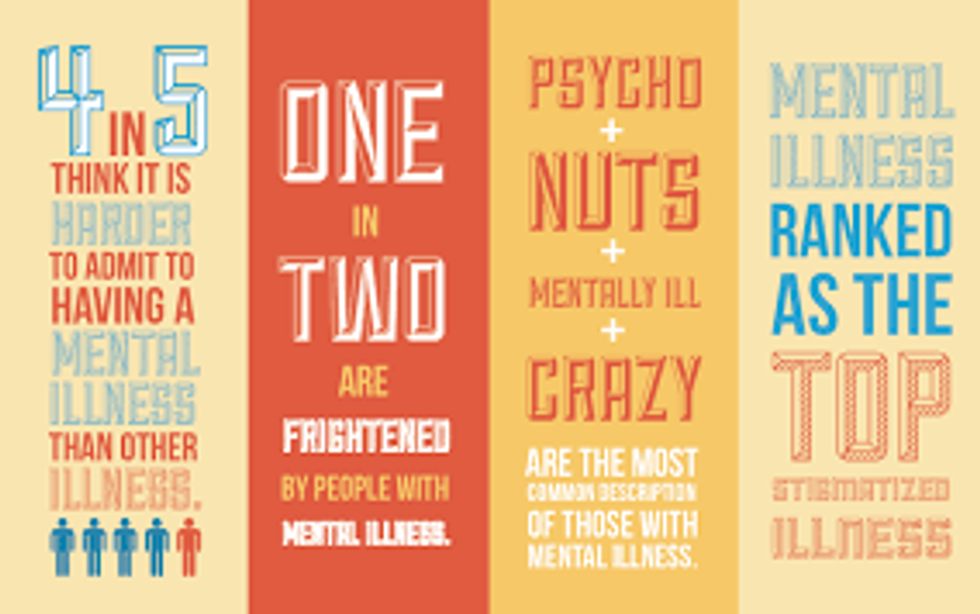

What’s the first thing you think of when someone says mental disorder? Someone crazy? A disheveled person who talks to himself and hallucinates?

Or maybe a woman who pulls out and eats her own hair? And what about when I tell you that nearly 1 in 5 Americans will deal with a mental illness or disorder this year? That means 100 of the classmates in your 500 person lecture, or 2 of your 10 closest friends. Every single person you walk past each day has a 1 in 5 chance, and so do you. Anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and countless other illnesses affect almost 20% of the population, and are often pushed aside or brushed over because they’re illnesses fought inside someone’s head and not by antibiotics, a cast, or their immune system. And out of those 45.2 million people, I happen to be one of them.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder with Obsessive Compulsive Tendencies is basically just a lot of big words that mean I get overly and uncontrollably anxious over things most people feel little to no anxiety about. When I was younger this used to mean uncontrollable scratching at my skin, biting my nails, stammering, insomnia, and nightmares. I spent the last two years of high school learning how to manage it, staying constantly busy because any idle time was spent deep in my anxiety. I would have panic attacks in my car during off periods or between school and work, and avoided going home because that’s where my anxiety was at it’s worst. Even well into my freshman year of college, I would skip class because walking alone across campus made me too nervous to leave my room. If no one could come to the dining hall with me, I just wouldn’t eat. I compulsively tapped my fingers against everything, and if my right hand brushed against the door when entering my room then my left hand had to touch the door, too.

By the middle of the year, it was incredibly clear that this wasn’t working. No amount of breathing, making lists, or going to the gym was enough to curb the way I’d been feeling. It was time to bring out the big guns, and by the end of freshman year I was taking anti-anxiety medication. It came with immense muscle pain and fatigue, but I finally felt free of the weight that accompanied being anxious about my every move. My mind was clearer than it had been since elementary school and it opened up my world.

But the important part of this story isn’t the ending. It’s everything that leads up to that. It’s that I was an outwardly normal teenager. I had friends, went to parties, played basketball, headed yearbook committee, worked in retail, babysat, got good grades, and seemed happy. I blended seamlessly with everyone around me, even though my head was a mess. We stigmatize mental illness and disorders to such a degree that people don’t feel comfortable reaching out and end up trapped. It shouldn’t have taken me so long to ask for help, but after years of being told to ‘just stop thinking about it,’ or to ‘just calm down,’ by parents, peers, and friends, I didn’t think I’d be taken seriously.

When someone falls and breaks their leg we don’t tell them to walk it off. Someone with third degree burns isn’t told to just put ice on it. So when are we going to stop telling people with mental disorders to just get over it?