This past semester I’ve done research on PWIDs (people who inject drugs) and harm reduction programs. The complexity and ever-forming layers to this single issue (which is interconnected to many other societal components) cannot be justifiably covered in such a short essay, but I will break it down to the best of my ability in as few words as possible. Due to my limited knowledge in anything outside injection drug use within the United States much of this article specifically refers to the limited research I have done.

Often times when the topic of drug addiction or abuse is discussed in classes I usually hear one or two classmates make arguments that it is the user’s choice, that drug use by injection is illegal, and that these people are selfish and nothing but trash. What if, like so many issues in this world, drug addiction wasn’t so painfully black and white? What if the general public and policy makers and health educators knew just how intricate and deeply reflective of our societal issues addictive drug use really is? To some the issue is simple: drug use is illegal and users should be put in jail. To others it is so convoluted it’s not even worth trying to figure out.

In my research I have found that not only are drug rehabilitation centers lacking in appropriate care for many PWIDs, but they lack much sway when the individual is placed right back in the environment in which their addiction had started.

Why do people use drugs?

There are various reasons why a person may try a drug, but addiction isn’t just something someone can overcome and conquer. Genetically speaking, some people are more prone to addictive behavior. With drugs like heroine, which are chemically composed to be addictive, the combination of the two plus many other variables makes for a completely complicated situation than can’t be solved by shipping people off to prison or rehab.

To top it all off the communities especially vulnerable to IV drug use are typically the people who face structural barriers and violence, poverty, stigma, xenophobia, internalized oppression, open oppression, and dismal opportunities to move forward. If drug use and illegal acts are what society expects of these communities there would come a point where many believe that is all they will ever be: washed up nobodies who live only to disappoint. This is absolutely not the case and when we take a moment to assess the full picture we see that there are so many of us set up for failure and when we do “fail” we’re cast aside; we become a statistic, robbed of our humanity.

What are the risks?

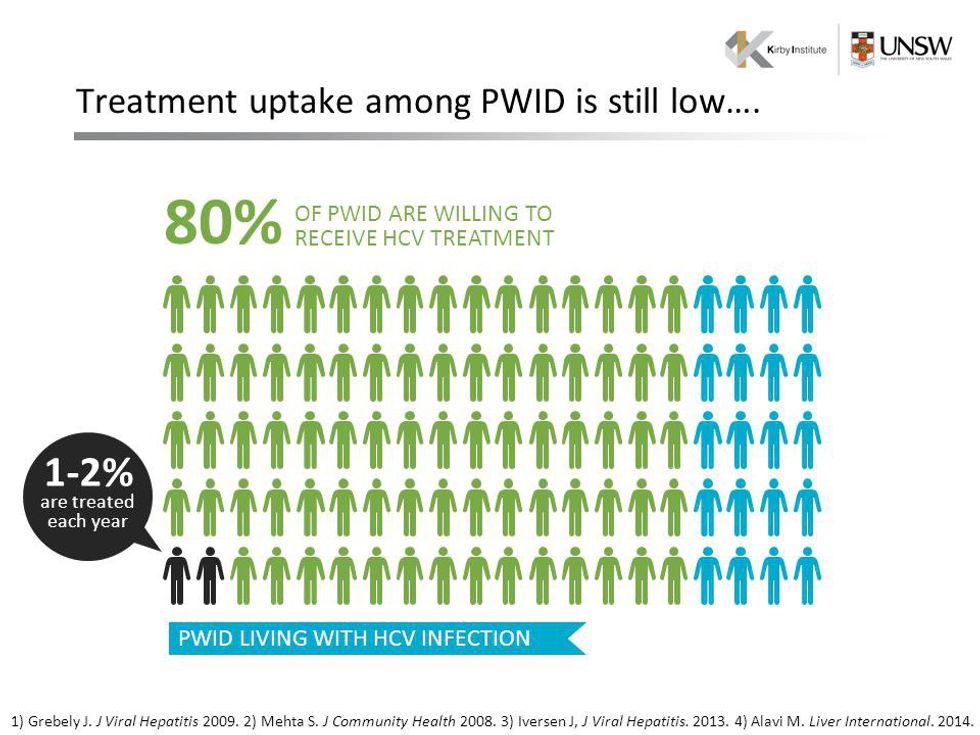

In these instances many PWIDs can’t afford to get a clean needle for every use. In some cases they will go to a shooting gallery where a group of people will gather and inject drugs together (sharing needles). The act of sharing needles is actually extremely dangerous. Between 2005 and 2014 the amount of PWIDs diagnosed with HIV had decreased by 63% and in 2014 about 6% of people living with HIV had been infected by unsafe needle use. There is the constant risk of getting caught with the drugs in possession. Even worse there is the risk of not being able to afford to feed the addiction and for many PWIDs that is a terrifying reality. These people are constantly living in fear and isolation.

What has changed and what can be done?

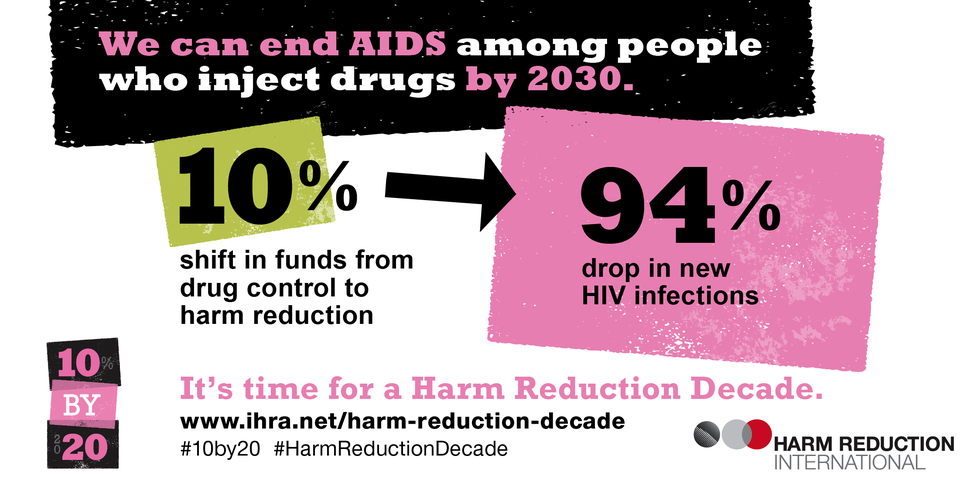

Abstinence as an answer to drug addiction and abuse works just as well as it does when it comes to sex education, which means it doesn’t work at all. People need to be educated in a way that they can understand, in a way that is comprehensive and applicable to their own lives. One of the best parts about harm reduction programs is the availability of resources and information. Free access to clean needles, counseling, and testing for HIV and other infections (and basic treatment) are just a small part of what harm reduction programs provide for these disenfranchised people in need. They are funded privately and by the state, though the funds are scant. Sometimes volunteers will hand out clean needles on the street, in other cases they will temporarily station in parks or trails and provide packages of information, needles, contacts for help, condoms, etc. The argument against these programs is that it is illegal. If someone is doing illegal drugs they shouldn’t be provided a means to further their illegal acts, right?

To make this relatable think back to when you first entered college. For many students drinking was an expectation regardless of whether you were of legal age or not. My school didn’t tell us to not drink, they taught us about how to drink safely and how much alcohol is in different kinds of drinks. They taught us about consent and who to call if you’re too drunk to drive. Drug use has been a part of human life for thousands of years, people aren’t going to just stop because it’s illegal.

Much of the issue in the US (you’ll find that harm reductions programs are actually more accepted in countries across the globe) is our use of the western biomedical model which is very black and white. Patients are seen as problems to be solved and much of the interpersonal warmth and healing (emotional and spiritual) is oftentimes forgotten. This is part of why many drug rehabilitation centers aren’t as effective for a lot of people seeking treatment. As was mentioned before, if a patient has finished their time in rehab, returning to the same bleak reality they were living in before can cause a lot of emotional stress. In many cases their friends were also users and their homes were sites where drug abuse was done. Perhaps their parents or a family member was involved, maybe they’ve been cast out of their community. All of these things can push a person to relapse into the same addictive, risky behaviors.

What you can do

I absolutely love talking about all the ways we can help people living with drug addiction. Stigma is a huge barrier many people have yet to jump over. Educate yourself on drug addiction and show compassion. Your reality in life could be a faraway dream to millions of others. The opportunities I have on a daily basis are far more useful and aiding in my future than many other people. Recognize your privilege, just as I have. Internalized oppression is invisible, even to the person suffering from it. If you feel the urge to judge a person who is addicted to drugs by saying they’re being selfish, that they are choosing to do it, stop and realize there may be a part of that person’s psyche that identifies as less than, as unworthy of being better. That kind of thinking isn’t an easy hurdle to jump.

If the topic of drug abuse or addiction is brought up in conversation or in class bring up harm reduction programs and structural barriers and internalized oppression. Try to get people to take a step back from judgment and policy and question: why? Why does this happen? In a life where someone feels like they have no control, drug abuse may be an escape. Giving them the opportunity to have harm reduction and multiple resources for treatment and counseling gives these people a sense of agency and power. Instead of pointing our fingers we can lend a hand. I know I said that drug abuse is not a choice, but that is mainly because PWIDs are living in a skewed world where they feel and believe they aren’t capable of making choices, or that they don’t deserve to make choices. Please rethink the way you look at drug addiction and help create a better world for those that have yet to realize there are hands reaching out and listening ears. Let's stop the stigma and strive for healing and compassion.

For more information on harm reduction programs visit this site: https://www.hri.global/harm-reduction-decade