Stereotypes of Homeschooling

Hannah Thomas

University of North Georgia

Abstract

Stereotypes are dealt with by every person no matter to which group they belong. Whether it be “crazy gingers” or “dumb blondes”, stereotyping is well known and often used in order to place people into an “appropriate” schema. Although stereotyping may not always be bad, the term seems to have become associated with negative connotation. Homeschoolers are one of the many groups of whom receive negative stereotypes more often than not. This paper will provide information concerning homeschoolers, summarize the general findings of the research done thus far, and use them to explain homeschooling stereotypes. As stated earlier, not all stereotypes are bad; this paper will touch on the generally known stereotypes of homeschoolers whether they be good, bad, or neutral. Each stereotype will be stated in a bold font, elaborated upon, and then presented in terms of research and statistical findings. The research within this paper is based on homeschoolers of all categories: homeschooled with no base curriculum (unschooled), homeschooled with some form of curricular structure, and homeschooled with specific structure (government approved curriculum or online classes). This paper will summarize the research done on this topic thus far and explain whether or not each stereotype is accurate in terms of statistical analysis based on research.

Keywords: social psychology, homeschool, stereotypes, research summary

All Homeschoolers are Conservative Christians

When comparing homeschoolers, public schoolers, and private schoolers, it can be seen that religious practices differ very little. Across all three, around half of students report being protestant (Christian), about a third report being Catholic, and the remainder fall into the “other” category (Bhatt, 2014). Historically, homeschoolers began as being predominately liberal in their concept of education thus leaving the traditional school system because they considered it to be too religiously based. Over several decades, the number of homeschoolers who report being Christian has gone up a bit, but the number still sits near the halfway mark (Bhatt, 2014). In the 1950s, over ten thousand families chose homeschooling because they viewed traditional schooling as too conservative and strictly structured (Lines, as cited in Romanowski, 2006, p. 128). That being said, in the 1980s the homeschooling population took a bit of a turn; schools began to cease practices such as regulated bible readings and prayers thus causing the more conservative and predominantly Christian families to convert to either homeschooling or private schooling (Lines, as cited in Romanowski, 2006, p.128).

Because of varying reasons in terms of ethics, Van Galen (as cited in Romanowski, 2006, p. 128) places homeschoolers into two groups labeled ideologues and pedagogues. Although ideologues’ choose to homeschool mostly due to religious purposes, their reasoning goes beyond the simple removal of prayers and bible readings in the classroom. On top of Christian practices, ideologues’ are concerned with the general teaching of ethics and morals; they do not believe traditional institutions to take these seriously as educational concepts. Because they believe traditional institutions allow religion, morals, and ethics to fall through the cracks, they choose to homeschool in order to educate their children to the extent which they deem fit.

On the opposite end of the argument are those whom Van Galen (as cited in Romanowski, 2006, p. 128) refers to as the pedagogues. Unlike ideologues, pedagogues are more concerned with the concept of independence and initiative rather than that of religion. They believe traditional schools to be emotionally and academically draining on children due to the nature of cliques, bullying, and the institutions tight leash on the allowance of creativity and individuality (Van Galen, as cited in Romanowski, 2006, p. 128). Pedagogues are the families of more liberal practices; they allow their children to learn at their own pace and encourage them take the initiative to seek out knowledge in topics which interest them.

Although both seem very different in opinion, studies done by Brian D. Ray (as cited in Ray, 2004b, p. 6) show that the most influential and common reason parents choose to homeschool is the desire for their children to have flexible curriculum, learning environments, and learn to be confident in themselves. No matter what religion or political standing, these parents want their children to learn about things that interest them, have opportunities to explore different hobbies and activities, practice taking initiative by learning at their own pace, learn from real life experiences, and make the most of their education.

Homeschoolers are Poor

The assumption that homeschoolers are poor is not only a generalized inaccuracy, but it is also proven to be irrelevant. Even so, parents of homeschooled children have approximately the same average income as any other family. The national average is $79,000 while homeschool families bring in $75,000-80,000 yearly (Ray, HSLDA, 2009). When it comes to income, it has been shown repeatedly that the level majorly impacts the academic achievement of those enrolled in public school systems. Children from low-income families perform more poorly while children from high-income families achieve higher scores (Ray, 2009). In contrast, homeschoolers not only perform well regardless of family income, they also outdo public schoolers in terms of academic achievement. Whether income is less than $15,000 or more than $100,000, homeschoolers consistently score in the 80th percentiles (Ray, 2009).

Homeschooled Families are “18 & Counting”

Homeschoolers do not all belong in the same category as the Duggar family. In fact, 86% of homeschooled families have four children or less; only 14% have more than four children. Homeschoolers average having three to four children while the general population averages having two children per family (Ray, HSLDA, 2009). Granted, this is higher than the national average for having four children (6%), but the statistics clearly show that homeschooling and “Cheaper by the Dozen” do not go hand in hand (Rudner, 1999).

Homeschoolers Don’t Actually Do School/are Unintelligent

Homeschoolers typically get a bad reputation for “not actually doing school”. This can be anything from “do you learn about physics at Six Flags?” to “automatically” getting A’s in everything (usually assumed cheating). Now, homeschoolers do have great field trips and leeway to take said trips during traditional school hours, but that does not mean they “never do school” or are “unintelligent”. In reality, all but eight states have government regulated requirements for homeschooled students (Ray, 2009). The majority of the states require parents to send in test scores, professional evaluation forms, and. some even require the curriculum be approved through the state (Ray, 2009).

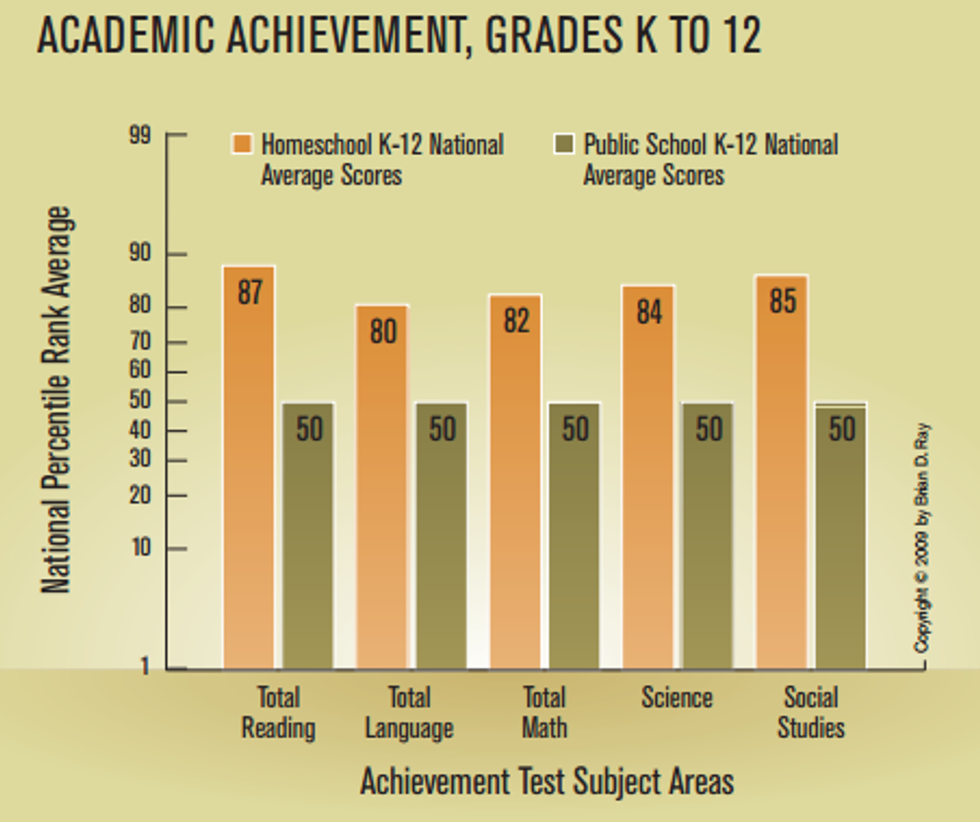

Not only are the parents required to prove their children are being educated, the children prove themselves via standardized achievement tests. Statistics show that, in comparison to children in the traditional school system, homeschoolers actually score higher on standardized tests in every subject across the board (Ray, 2000; see Appendix A for score comparison graph). Traditional school attendees score, on average, in the 50th percentile on standardized tests while homeschoolers average scores in the 65th to 80th percentiles (Ray, 2009). In terms of college entry, homeschoolers show higher scores on the ACT and SAT than their traditionally schooled counterparts. On the SAT, homeschoolers score an average of 568 in the verbal category and 532 in mathematics, while traditionally schooled students score an average of 501 in verbal and 510 in mathematics (Ray, 2004a). The ACT shows similar results: homeschoolers average an overall score of 26.5 compared to the traditionally schooled average of 25.0 (Cogan, 2010).

Homeschoolers Will Have Difficulty Transitioning to College

Not only are homeschoolers more likely to graduate high school with higher GPA’s, they are also more likely to do the same in college, in addition to being more likely to attend college to begin with. According to Michale F. Cogan (2010), homeschoolers not only graduate high school with a higher cumulative GPA than their traditionally schooled peers, they also maintain better GPA’s throughout their college experiences. Homeschoolers graduate high school, on average, with a GPA of 3.74 compared to traditionally schooled students’ average GPA of 3.54 (Cogan, 2010). By the end of their first year in college, previously homeschooled students maintained an average cumulative GPA of 3.41 compared to traditionally schooled students’ cumulative average of 3.12 (Cogan, 2010). Lastly, when comparing the cumulative averages at the time of graduation from a four-year college program, homeschoolers showed a cumulative average of 3.46 while traditionally schooled students showed a cumulative average of 3.16 (Cogan, 2010).

Many colleges, even Ivy League, often not only welcome, but also recruit homeschoolers for their programs (Romanowski, 2006). Oftentimes speakers from these schools will attend homeschool conferences, give lectures and workshops, and even offer special scholarships as forms of recruitment for homeschooled students (Romanowski, 2006). In general, homeschoolers are more likely to attend college, or take college level courses, than their traditionally schooled peers. To put it into perspective, more than 74% of homeschool graduates take college level courses in comparison to the 49% of the national general population (Ray, 2004a).

As for college graduation, homeschooled students are more likely to graduate from a four year program than traditionally schooled students. The graduation rate is 66.7% for homeschoolers, and 57.5% for traditionally schooled students (Cogan, 2010). This could be partially due to the fact that homeschoolers take advantage of joint enrollment opportunities more than traditionally schooled students. Homeschoolers begin college with an average of 14.7 hours earned prior to high school graduation, while traditional attendees averaged only 6.0 credits prior to enrollment (Cogan, 2010). Although, early on, homeschoolers may not experience the same in class setting as traditionally schooled students, by junior and senior years of high school, homeschoolers are more involved in college classrooms.

Parents are Not Qualified to Teach Their Children

Many question whether parents are qualified to teach their children. After all, the majority of traditional teachers have teaching certifications earned through many years of schooling. Though, when looking at the statistics, it is clear that parents of homeschooled children have significantly higher academic standings than the general population of parents (Rudner, 1999). An average of 88% of mothers whom homeschool have gained at least some level of college experience with over half of them holding a degree (Rudner, 1999). As for fathers of homeschoolers, 90% have some form of college experience with nearly 75% having a degree of some kind whether it be associates, doctorate, or anything in between (Rudner, 1999). In comparison to the general population, with less than 50% of both mothers and fathers having college experience, these numbers are very impressive (Rudner, 1999).

Even with the question of teaching ability, the certification level of parents has little to no influence on academic achievement amongst homeschoolers (Ray, 2009). The government does not even see it as a problem, considering they do not require parents to have an education degree in order to homeschool their children. Ray (2009) conducted a study involving 8th grade academic achievement composite test score in comparison to the parents’ level of education. The results showed that students score in the 88th percentile when both parents have a college degree, 80th percentile when one parent has a degree, and in the 66th percentile when neither have a college degree (Ray, 2009).

Even over the course of the entire 12 years of schooling, parental education status has little effect. Whether one parent is certified to teach or neither are certified, children show average academic achievement within the 80-90th percentile range (Ray, 2009). Whether their mother has a college degree or only some college experience, children show academic achievement within the 80-90th percentile range. Whether or not their mother even graduated high school, the children still score in the same range. Over the course of all twelve years, homeschoolers still show higher academic achievement than the average traditional student even if their parent has less than a 12th grade education (Ray, 2009).

Homeschoolers are Socially Deprived

People often think that homeschoolers are awkward, shy, and/or socially inept, but statistics say otherwise. Many believe that “socialization” can be defined simply as interaction with peers, such as classmates. Because of this, it is often assumed that homeschoolers do not know how to function socially due to their limited peer interactions. On the contrary, statistics show that homeschoolers actually develop as well as traditionally schooled children, if not better (Medlin, 2000).

Homeschoolers and their parents argue that socialization is equally as dependent on interactions with people with whom they have no relation, but do not fall into the “peer” category (Shyers, 1992). These scenarios can include things such as adult interaction, and interaction with children significantly older or younger. Traditionally schooled children interact with children in their classes and afterschool activities, limiting the age range of their social interaction group. Homeschoolers often interact with many people of all different ages; it is not uncommon for a seven year old to have a best friend of eleven years.

It is also common to see traditionally schooled children separate themselves into groups or cliques; this often results in an “in-group vs. out-group” effect further lowering the number of friends the children are around regularly. In-group and out-group also are more likely to result in bullying and negative influence, especially in elementary and middle school. By having a group of children ranging all ages, homeschoolers learn how to cooperate with one another and solve problems that may arise due to age differences. Overall, homeschooled children get along significantly better with their peers than those whom are in traditional school settings (Shyers, 1992). The data allows one to form the conclusion that socialization can be gained in more ways than interacting with classmates (Shyers, 1992).

Homeschoolers also tend to be more involved in community activities with many of them being involved in numerous groups (Shyers, 1992). These include 4H, religious institutions, library functions, FFA, scouting, and YMCA, amongst other things (Shyers, 1992). Being heavily involved in the community allows homeschoolers to develop a sense of achievement, confidence, and initiative. Brian D. Ray (2004) did a study that showed 98% of homeschoolers as being involved in more than 2 social activities; this included things such as music classes, sports, ballet, and numerous other activities that expose children to peer interaction. Overall, homeschoolers have more opportunities to explore different interests resulting in higher self-concept amongst homeschoolers in comparison to traditional schoolers (Ray, 2004a). These opportunities also expose them to numerous age groups thus allowing them to learn interactions that are appropriate for adults and children. These children are more respectful to people in general, and more open to the idea of differing opinions (Ray, 2004a).

Homeschoolers Have No Lives

Homeschooling schedules are far more flexible than those of traditional schools; this allows children to use their time exploring numerous interests and participating in events that otherwise would be impossible. While traditionally schooled children are in the same classroom(s), with the same people, doing the same things, at the same times every single day, homeschooled students have the flexibility to deviate from scheduling (Ray, 2004b). They have more opportunities to change their learning environment, play outside, and interact with siblings or have playdates during the day. There is freedom to go to the library, do school outside or in different rooms within the home, get up and move around, etc.

In high school, they have more opportunities to participate in internships, mission trips, activities, and community service projects that would typically take place during traditional school hours (Ray, as cited in Ray, 2004b, p. 6). As a result of having more opportunities to participate in activities and events of interest, homeschoolers report higher excitement levels and overall happiness with their education and lives in general. When given the options dull, routine, or exciting, 73% of homeschoolers report their lives to be exciting as opposed to 43% of the general US population (NORC, as cited in Ray, 2004b, p. 5). As for happiness, when given the options of unhappy, pretty happy, and very happy, 59% of homeschoolers report their lives to be very happy as opposed to 28% of the general US population (NORC, as cited in Ray, 2004b, p. 5). Obviously, homeschoolers are not missing out on life’s adventures. If anything, they are taking advantage of everything life has to offer.

Homeschoolers are Incapable of Functioning in the Real World

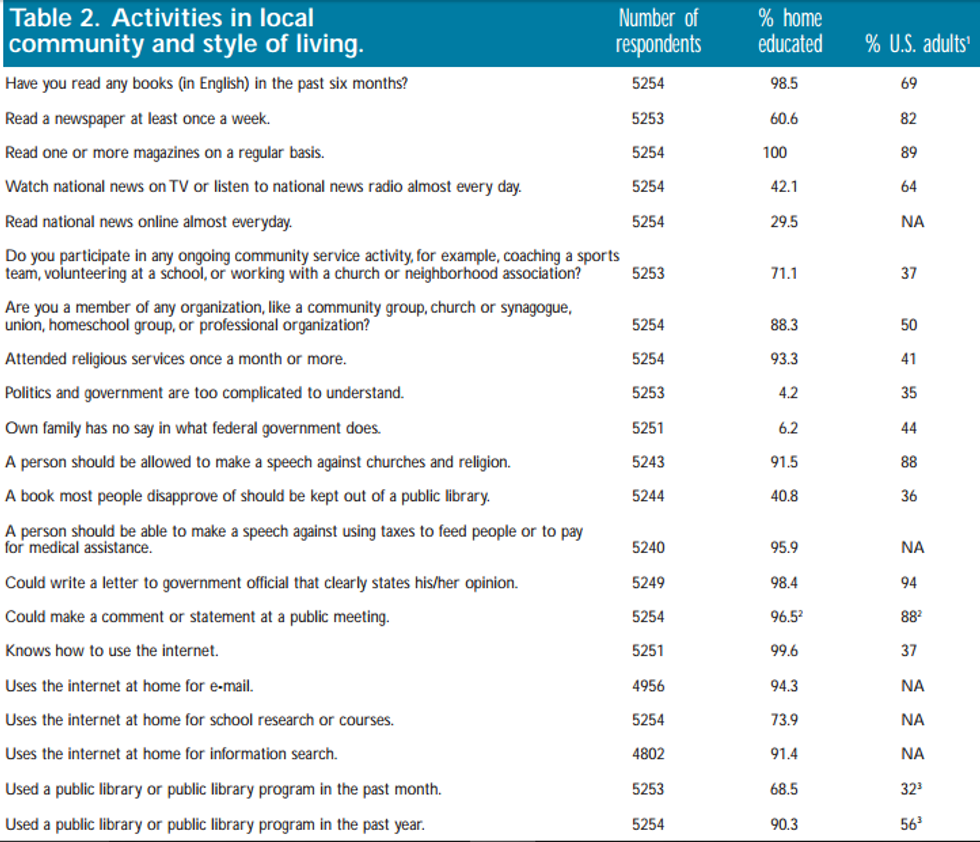

Homeschool graduates are more likely to be involved in political engagements in their communities. According to Ray (2004a), 35% of the general US adult population view political and governmental endeavors as too difficult to understand in comparison to only 4.2% of previously homeschooled adults. Because of this, previously homeschooled adults are more likely to participate in political events, attend public meetings, donate money to the cause of said candidates, contribute their vote during elections, and are generally more civically engaged than the general population (Ray, 2009).

Homeschool graduates are also significantly more likely to be involved in community service projects, volunteer work, and community organizations (Ray, 2009). Seventy-one percent of homeschool graduates are involved in community service projects, such as coaching children’s sporting teams or volunteering in religious affiliations, as opposed to the general populations’ average of 37% (Ray, 2009). Homeschoolers also hold higher rates of participation in community organizations; they reside at 88% while the general population consists of only 50% (Ray, 2009).

Conclusion and Future Study

While some stereotypes of homeschoolers holds a relative amount of weight conceptually, these stereotypes are often overly exaggerated or inaccurate altogether. Homeschoolers perform more highly, are more sociable, and contribute more to the community than the average US citizen, as opposed to popular beliefs. One stereotype that contains little to no research is that of homeschoolers being uneducated in terms of pop culture. Many people believe that homeschoolers live under a rock (metaphorically speaking), and are sheltered from seeing movies, listening to music, or keeping up with social media and celebrity gossip. Research on this subject could benefit greatly to the continuation of breaking down stereotypes and learning more about different educational techniques and preferences.

References

Bhatt, R. (2014). Home is Where the School is: The Impact of Homeschool Legislation on School Choice. Journal of School Choice, 8, 192-212.

Cogan, M. F. (2010). Exploring Academic Outcomes of Homeschooled Students. Summer 2010 Journal of College Admission, 18-25.

Medlin, R. G. (2000). Home schooling and the question of socialization. Peabody Journal of Education, 75(1 & 2), 107-123.

Nolin, Mary Jo, Chapman, Chris, and Chandler, Kathryn (1997). Adult civic involvement in the United States: National Household Education Survey [NHES].Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Publication number NCES 97-906.

Ray, B. D. (2000). Home Schooling: The Ameliorator of Negative Influences On Learning? Peabody Journal of Education, 75(1&2), 71-106.

Ray, B. D. (2004a). Home Educated and Now Adults: Their Community and Civic Involvement, Views About Homeschooling, and Other Traits. Salem, OR: NHERI.

Ray, B. D. (2004b). Homeschoolers on to College: What Research Shows Us. Journal of College Admission, 185, 5–11.

Ray, B. D. (2009). Home Education Reason and Research: Common Questions and Research-Based Answers About Homeschooling. Salem, OR: NHERI.

Ray, B. D., HSLDA. (2009). Homeschool Progress Report 2009: Academic Achievements and Demographics.

Romanowski, M. H. (2006). Revisiting the Common Myths about Homeschooling. The Clearing House, 125-129.

Rudner, L. M., & Home School Legal Defense Association, P. (1999). Scholastic Achievement and Demographic Characteristics of Home School Students in 1998. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 7(8).

Shyers, L. E. (1992). A comparison of social adjustment between home and traditionally schooled students. Home School Researcher. 1-8.

Appendix A

Statistics for Ray, D. Brian. (2009).

Appendix B

Statistics of Homeschool Graduate Involvement

Nolin, Mary Jo, Chapman, Chris, and Chandler, Kathryn (1997).