"Spirited Away" was released back in 2001; it was a hit with critics and audiences alike, both praising its mingling of fantastical and shockingly real themes, particularly notable for what is, ostensibly, a kids’ film. It was not only entertaining but relevant, and it’s only become more pertinent today. Specifically, the character No Face serves as a poignant criticism of consumer culture, in particular, curiously, the internet society that budded after the film’s release.

"Spirited Away" has a sort of "Alice in Wonderland"-esque vibe to it, following the trials of a young girl trapped in a world that defies any familiar convention. It opens on whiny ten-year-old Chihiro moving with her family. After taking a wrong turn, they stumble upon a world of curious spirits, where Chihiro’s parents are transformed into pigs for their gluttony and she’s forced to take a position at a spirit batthouse to earn their freedom. Paradoxically, the story becomes more real as we delve deeper into this peculiar world. Defined by exploitative greed and corruptive materialism, the bathhouse quickly becomes a clear representation of our world’s capitalism, its inhabitants, though fantastical, caricatures of human traits.

No Face is introduced as a lonely creature, keenly interested in others but rarely interacting and, on his own, incapable of communication beyond subtle nods and soft, beckoning grunts. Despite his eerie design, No Face is appears to be one of the gentler spirits: he helps Chihiro secure a much-needed bath token in thanks for letting him into the bathhouse out of the rain.

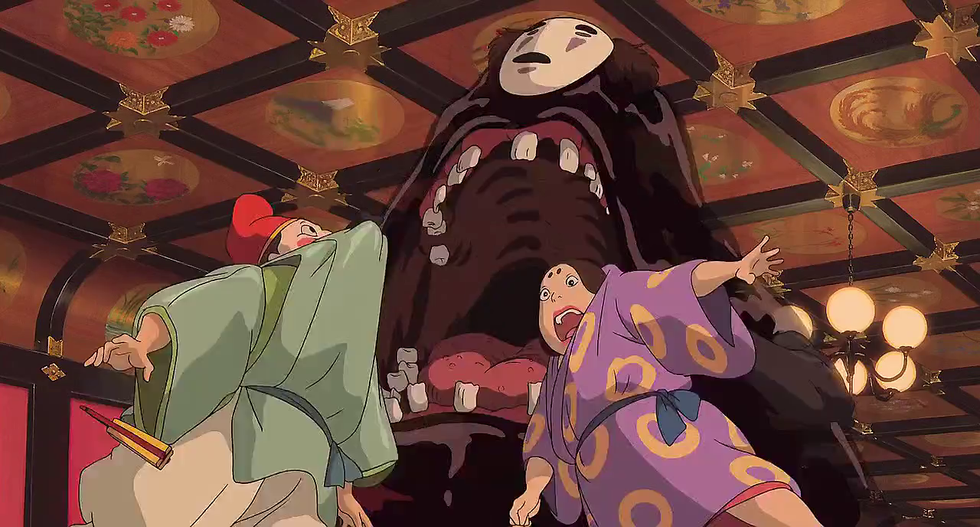

He initially follows Chihiro, offering her more gifts, until -- after Chihiro rejects further tokens that she doesn’t need -- he realizes that extravagant offerings can elicit similarly kind responses out of others. By the next morning, he’s generating gold from thin air, attracting the sycophancy of the entire bathhouse. He mistakes the praise and food they rain upon him for meaningful affection, filling his desire for companionship with their material comforts and shallow flattery. Gradually, he consumes more and more of the bathhouse’s greedy character until it completely overwhelms him, turning him into a horrible, globular amalgamation of the business’s worst traits.

The name “No Face” could be intended to give the character a sense of ubiquity, or it could refer to his inability to create an identity outside of what his environment impresses upon him. Either way, he’s made to be a consumer, not only of the bathhouse’s products but of its twisted values, another faceless victim of a system that mercilessly feeds on humanity and turns it into monstrosity.

Maybe “humanity” isn’t the most accurate word to describe an amorphous, shadow-like spirit. But despite his indeterminate species, he captures a distinctly human aspect, one that’s becoming progressively more universal. We live in a culture swollen with consumerism, and as the internet grows more and more all-consuming, it’s hard to avoid being bombarded with images that tell us we have holes inside, holes that can be filled with image and cheap material. Superficiality is a painful part of internet culture, one that we have to monitor as the internet becomes more omnipresent. Progressively more targeted ads and the quick, shallow images encouraged by online profiles and comments sections tend to deny genuine connection, attempting to replace it with surficial interaction and fleeting impressions. We are being pushed more and more to follow No Face, to indiscriminately absorb and consume. But with the growing presence and vitality of the internet, we might not be able to purge ourselves and escape.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.