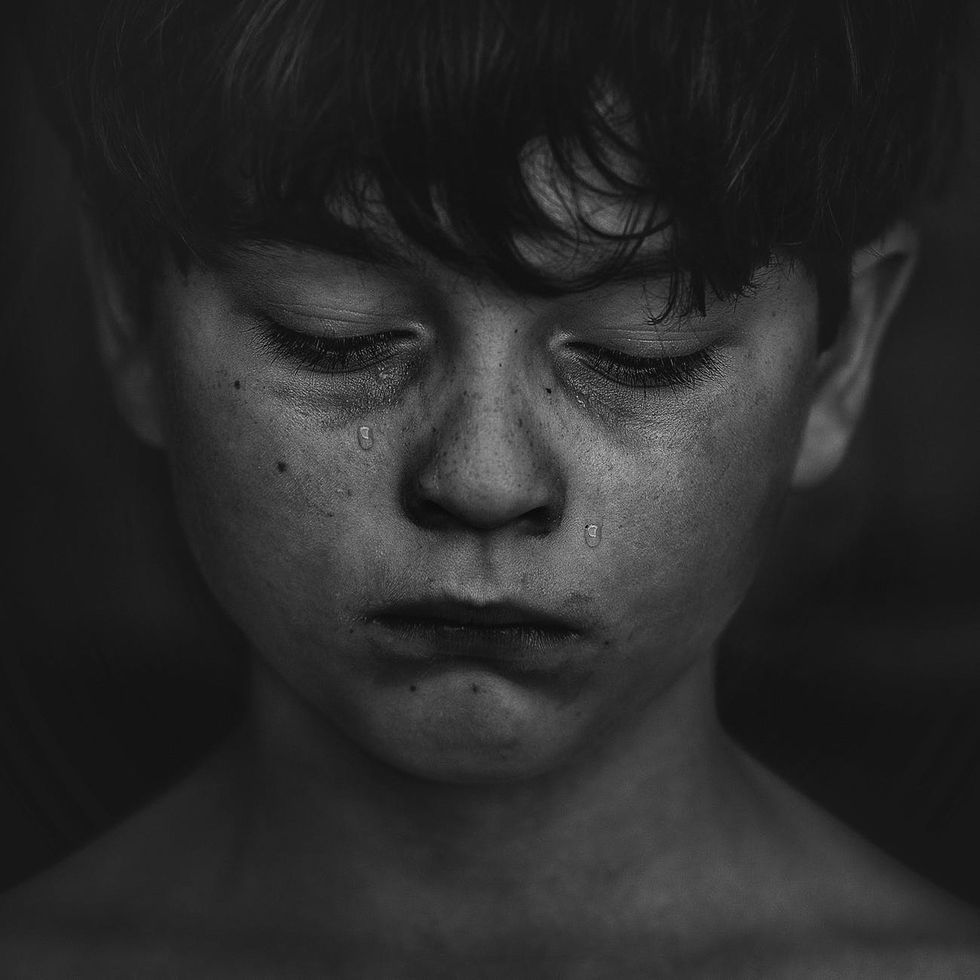

This week, I'm writing another meditation, this time on Emmett Rensin's "The Alien and Mundane," published in The Believer on June 7, 2017. An in-depth look into the "alien" and "mundane" ways we grieve, it starts off, like most of his articles, in a very riveting way: Rensin had a friend at the University of Chicago whose mother died when she was little, and although she finished mourning long ago, "she had not yet overcome the need to mourn. I never saw her more disturbed than on the day she realized...it was the anniversary of her mother's death. She had nearly forgotten." She wasn't crying for her mother, but rather Rensin "saw her cry for her guilt."

He labels these types of mourning "guilty mourners." On forums all over the internet and self-help books all over Barnes & Noble bookshelves, people all over the world grieve not for the lost or the tragedy, but for their guilt. They are "worried that they are heartless freaks. They worry because they believe they are getting over total disaster with too much ease. The world has changed forever, they insist, but they keep forgetting. One woman on a message board wrote about her first response to the Twin Towers burning on September 11, 2001, as the towers were still burning on TV: "Oh, this is really going to fuck up my date tonight."

Everyone, in these forums, asks the same question: "Is there something wrong with me?"

Sigmund Freud in "Mourning and Melancholia,"examines the question of grief. For him, this condition of banality and mundane is the "redirection of the conscious mind"and "a work of mourning." This is described as "healthy mourning," where we "divest the dead of their importance." "The fact is...when the work of mourning is completed, the ego becomes free and uninhibited again." We start to worry about food, work, and other everyday concerns. Freud explains that the only alternative to feeling this way is melancholia, and melancholy is "the failure to mourn" which sometimes results in suicide.

However, if we applied rules of Freud's work universally to the human condition, we would clearly be in a lot of trouble. But we can learn from his differentiation between healthy mourning and melancholy. "The guilty mourner is troubled, more troubled than they are by death itself, because there is something narratively backward in their healing." Simply put, it's not what we expect from mourning - to be mourning our own guilt instead of what actually happened. The Freud narrative is the alternative, that "the return of the mundane is not the failure of action, but the action itself."

Rensin returns with another example, this one one of the extreme. He uses a case from when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a "catastrophe for which there was no language....not a violence anybody knew to be possible." Even in this, as shown in John Hersey's "Hiroshima,"we see the mundane form of grieving in one character, Dr. Fujii. Dr. Fujii was in an extraordinary amount of pain from his burns, but his first remark to another person was that "he looked like a beggar, dressed as he was in nothing but torn and bloody underwear."

Another character featured in "Hiroshima," Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto, walked across a ruined street in the middle of the burning city. He saw that houses were destoyed, people were screaming for help under many of the ones that were burning. But he ran past them to find his wife - and the only thing he says upon seeing her is "Oh, you are safe." Reverend Tanimoto and his wife go their separate ways, and Tanimoto realizes that he pays more attention to the mundane of his family than to the devastation of the city. "After all of this, it is odd to remember that he has an ordinary life. But he does."

Rensin then references the story of Jo Ann Beard, a colleague of five people who had died in the 1991 University of Iowa Shootings. She goes into work on Friday and has to leave work early - she needs to take care of her dog, who is old and sick. After she leaves, a graduate student then kills five of her colleagues and then kills himself.

Beard knows that "the word changes," but nevertheless, the shooting is only "a brief intrusion. It is a brief atrocity, dispassionately related in a single section, up-ending the whole essay." After the brief moment of terrifying grief, life goes to a new type of normal - she returns back to the couch she's sleeping in, still taking care of her dog, "just as they were before."

"We don't struggle over the pit of melancholia, tempted by our grief. Ordinary life can't help digesting tragedy. The mundane sees the alien and consumes it, just swallows it up." Rensin goes on to note that the mundane conquering the melancholy of the alien is not a distraction, but a sign of something more.

The mundane is not the absence of grief, but the processing of it before we are ready to actually be melancholy. "These banalities are at odds with whatever catastrophe is at hand, and the fixation on them functions as a distraction, or as a necessary element of mourning, or as a sin, until the catastrophe can be processed and absorbed into a reunified experience of life." In both stories of Hersey and Beard, life goes on, regardless of whatever catastrophes happen, but there are two different ways that life goes on. For Hersey, "life goes on, but there is no 'return' from something like the atomic bomb." For Beard, "one returns to the mundane because there is nowhere else to return."

We feel guilty about not being melancholy, about seemingly not grieving. And this terrifies us. "The mourner who asks, Why am I so preoccupied with the normal? is asking, really, Is this normal now?" This guilt is not a trap to not grieve, but rather a warning. Tragedy is around us everywhere. How much time would we truly have if we were to mourn every single injustice and devastation in the world, from school shootings seemingly every other week to tsunamis and earthquakes that kill thousands? The mundane, for better or worse, teaches us to survive. "Has the world changed so much and so suddenly that I can no longer even feel the difference? the guilty ask. The answer is yes, and it is happening, has happened, all the time."

I distinctly remember last December when I came home for winter break. My mom picked me up from LaGuardia airport, and immediately I noticed there was something different - her voice was more hoarse, there were new scars around her neck. "I have thyroid cancer, and just had surgery," she said.

"Oh," was all I responded.

We moved on, and I talked about what it was like at school, and how things were at home, from topics as mundane as the latest issue with our car to whether I was eating well at school. I know now that that was how I grieved upon finding out the news. The mundane is a survival mechanism - not a lack of empathy.

"Things are fine," she said. "Just worry about school and make sure you're eating right."

"Oh. Okay," I said.

I woke up at 3 a.m. the other night, shaking, uncertain what about but just with the sense that something was dreadfully wrong, that the new normal maybe shouldn't be the new normal. For me, the mundane is the precursor to the melancholy - and sometimes, we grieve by not grieving. We feel guilty about our lack of mourning. We put off the melancholy for a later time because sometimes we're not ready yet.