Sometimes when I'm alone

I cry because I'm on my own

The tears I cry are bitter and warm

They flow with life but take no form

I cry because my heart is torn

and I find it difficult to carry on

If I had an ear to confide in

I would cry among my treasured friends

But who do you know that stops that long

To help another carry on

The world moves fast and it would rather pass you by

than to stop and see what makes you cry

It's painful and sad and sometimes I cry

and no one cares about why. –2Pac Shakur

Black men are hurting. As black men trying to survive in America, we demand that we are respected as human beings. The toxicity that we know as hypermasculinity has affected my melanated kindred and me for eons. Since slavery, we have been repudiated of our freedoms and civil rights, stripped of our identities and have been demonized as sub-humans who are incapable of having emotions. Black male hypermasculinity has been utilized as a culturally hegemonic tool, which reinforces negative stereotypes of black men across the Internet, the news, magazines, and the radio.

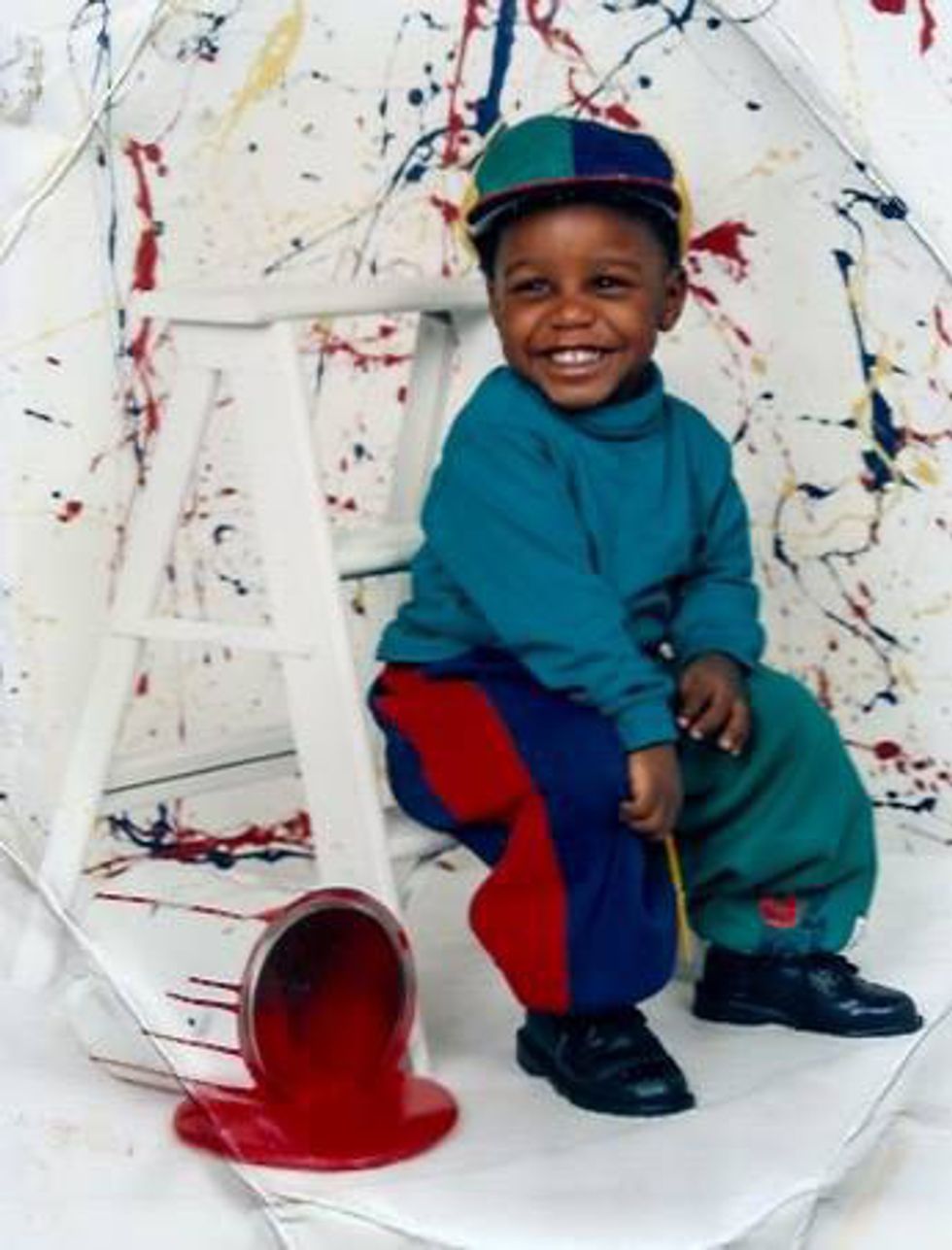

I will profess one of my experiences of black hypermasculinity, a few of its corrosive aftereffects, and lastly, emotions. Emotions are integral to what makes you and me human. Emotions are a facet of black humanitarianism. Growing up, I was both a hyperactive and reticent child. Though I had days where I kept most of my feelings to myself, I was a very sensitive person. At the end of the day, I was always smiling:

Throughout my academic life: elementary, middle and high school, I hardly interacted with my classmates. I rarely talked to my parents. From when I left for school to when I got off the school bus, my mom would ask me how my day was.

I was often irritated and upset with myself. Reluctant to say anything, but aching to explain how my day was, I gave brief responses to her like “fine” or “don’t worry about it.” My mom would look into the languor in my eyes. She in a worriedly frantic tone of voice, would ask me what was wrong.

"Please, tell me what's wrong. You know I love you. You can talk to me anytime," She'd say.

Before I would get the chance to speak, she'd impulsively urge me to give her a hug. I would irritably refuse to hug her. Sometimes, I wouldn’t even look back at her to respond. I’d willingly glare straight. I was afraid of saying anything to her. I was afraid she wouldn’t understand.

I was afraid that if I uttered words concerning my feelings, I’d get so panic stricken that I’d start whimpering. It would worry her even more. I had made myself believe that even if I told my mother what was bothering me, there would be nothing she could do about it.

I hated crying. I hated feelings. I hated them both so much that I’d internalize my own feelings and condemn myself for crying or for the simple fact that I had feelings. I held the preconceived belief that having emotions depicted me as a weakling.

Today, I can still recall hearing rude, dismissive remarks such as “get over it,” “be a man,” “grow a pair,” “stop complaining” and “don’t let it get to you.” I can proudly say I am more open about my feelings than I was five-plus years ago. If I always repressed my emotions and pretended this racist, judgmental society has never affected me socially, economically, institutionally, racially and psychologically, I’d be perpetuating the myth of black hypermasculinity. Today, as black men, we are still stigmatized by both our black community and our white counterparts.

Gangsta rap, being one of the most prominent subgenres of rap music, is predicated on an essentialized, and limited construction of a hyperbolized black male subjectivity. But what is black hypermasculinity? Black hypermasculinity is a social construct represented by a white male patriarchal perspective.

This construct exaggerates black men as over-domineering, super-powered, callous, deranged, insensitive and animalistic brutes. Black hypermasculinity is the racist, deprecating term used to dehumanize the validity of black humanitarianism.

Some black men might exhibit more “masculine” traits than white men, however, that does not make a black man more or less viable than his white counterpart. In the mid-'90s era of hip hop, the music industry has reinforced the idea of black hypermasculinity, and still to this day, it manifests itself through aggressive verbal battles, and physical disputes.

In gangsta rap etiquette, several rappers in their fluid and eloquent, but rugged, braggadocios and brash lyrics, have engaged in hyperbolic masculinity. Moreover, it dictates a volitional desire for violence. Rhyming about their virility, strength and exaggerated invincibility, imagined or real deaths of a competitor that induces no remorse or sorrow. These characteristics alone negatively reinforce the personification of black men in gangsta rap music in American society.

In this society, we as black men are condemned for showing our feelings, let alone admitting that our feelings exist. Our white counterparts demonize and denounce our humanity. Some whites are surprised by the fact that we are no more human than them. By our own black community, we been mocked, teased and dismissed for exhibiting our humanness. This must end.

In order to dismantle this ongoing stigma, we must show our emotions. We must show our vigor. We must show our happiness. We must show our anger. We must show our loneliness. We must show our melancholy. We must show our guilt. We must show our bitterness. We must show our tears.

Crying is a natural response to our pains and our joys. Our cries should be resonant ones, cries of cathartic release, cries of our brethren who are weaponized wherever we go, cries of our brethren ruthlessly being murdered near their homes, in the streets, with no logical, justifiable premises as to why. We must show feelings because feelings are an integral facet of manifesting humanness.

We are human beings, and we demand that we are respected as human beings. With that said, I urge you, black men of America...to cry.