I recently went to a scientific conference in San Francisco where I had the good fortune of attending a panel led by Ann Reid, the director of the National Center for Science Education (NCSE). The title of the session was “How Do You Solve a Problem Like Science Denial? One Conversation at a Time.”

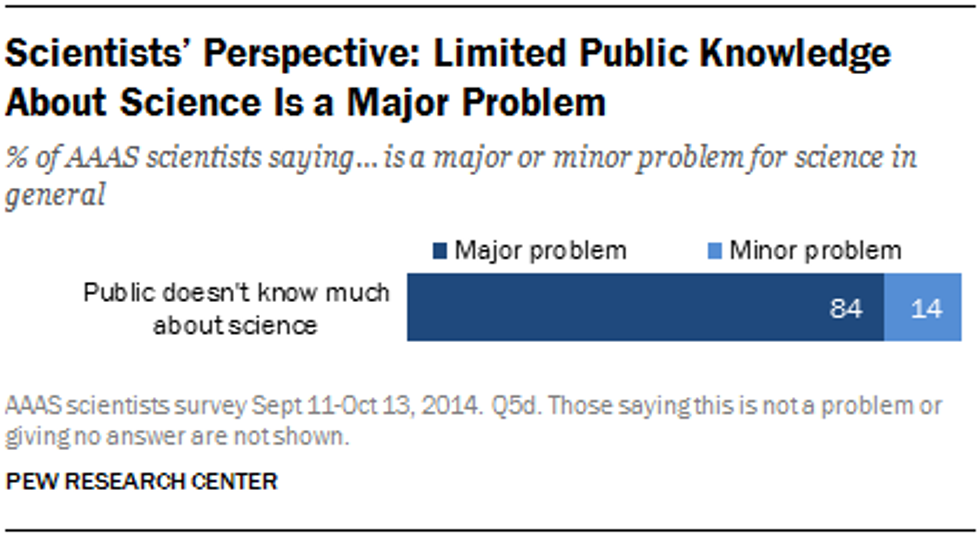

I was deeply intrigued by this topic, and I’ve written on this topic before. In this past election, science has come under assault from many fronts, with climate change facing the brunt of the attack, but also including vaccinations and abortion. There is an enormous gap dividing the opinions of the general public and scientists on major issues. Science has become vilified for the sake of politics, and all this is exacerbated by agents who actively seek to undermine science and spread misinformation. It is the critical responsibility of scientists to engage the public and make it more accessible and more widespread among the general public.

As a budding scientist myself, I’m often faced with the frustration that comes with trying to convey a complicated scientific idea to someone who is not from the same educational background as myself. Some of these people are family, some are friends; they are well-educated and smart. Most of them have confidence in the scientific method and evidence when presented to them. However, a few choose to selectively filter out scientific facts that contradict a preconceived belief, either a result of misinformation acquired elsewhere, or due to a personal and emotional conviction such as religion. Although it can be challenging to engage with this subset of people, they are also the people that need convincing. There are always going to be people who disagree with you. But as long as they are intelligent and willing to have a conversation, you can work with them.

In her talk, Dr. Reid presented six major points to keep in mind when combating denialism. I will outline them here:

Ask questions

It is important to understand the person you are talking to: ask them why they believe the things they do, what their source of information is, and what they think is correct. Try to understand what is important to them before you start barraging them with knowledge. Remember that you are having a conversation, not giving a lecture.

Listen respectfully

Often you might be faced with the overwhelming urge to just refute everything the other person says, scoff at their ignorance, shout references to literature at them, and flip the table. Try your best not to do that. Yes, it can be frustrating when hearing a person say with conviction that climate change is a hoax. But you are a scientist, so act like one. Listen respectfully to their side of the argument, listen to their position and circumstances that led to their beliefs.

Be personal – tell your story

Again, this must be a conversation. Tell them who you are, what you think, why you think it. Don’t pose yourself as a smug, elitist, big-headed scientist. Be a human being that they would feel comfortable talking to, and will therefore listen to as well.

Don’t teach; model scientific thinking

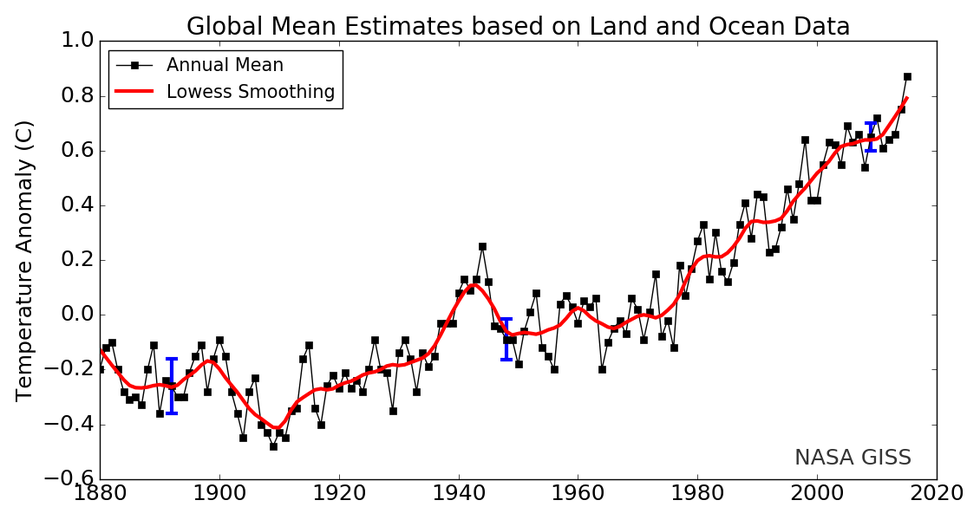

This is perhaps the most important item on this list, and the point I found most enlightening. Don’t try to open up their brain and pour in a gallon of knowledge; try to make the other person derive the conclusion on their own. A great example is when dealing with climate change denialism: instead of giving them statistics on global temperature rises, ask them “what would convince you that temperatures around the world are increasing?”

I want to see data on temperature records collected over the past several decades.

That’s great, here are temperature records from 1880 to 2015 that do show exactly that.

Very well, but how does that even happen, and how do we know it’s not a natural cycle?

We know that carbon dioxide gas (CO2) in the atmosphere traps heat from the Sun. We have records of the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere since 1960 that show an increasing trend. We can also track the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere resulting from burning fossil fuels, and calculate the effect humans have had on CO2 levels.

Okay, but what about all the controversy among scientists? How do I know who’s right and who’s wrong?

Actually, there isn’t a lot of controversy among scientists. They all agree climate change is real and it’s serious. Those that don’t have either been refuted, or have conflicts of interest that bias their views.

So there you go—there’s the data, now draw your own conclusions. You can imagine extending the above example to other "controversial" scientific concepts such as evolution and vaccines.

Don’t come to fight, come to win

This might sound uncharacteristically aggressive, but that’s not the case. The message is pick your battles. From the above example on climate change, no person you talk to is going to come out of your conversation having seen the light of truth and immediately go home to compost their trash. If you can at least get them to say “Hmm, I see your point. I never thought of it that way” you’ve already won. Remember your goal: the point is to get people to question themselves, not try to win an argument with overwhelming data.

Remember your audience

When you have this conversation with one person, remember you’re not just talking to that single person. Your talking to everyone around you, and also indirectly to everyone else that person talks to afterwards. Be respectful and aware of the larger influence your conversation is having. Inspire confidence in your words by showing them that you are not driven by emotion or personal agenda, but rather by facts and objectivity.

This holiday season when you go visit friends and family at home, don’t shy away from controversial topics such as this. Engage with people about science, but don’t fight them. I genuinely believe it is our imperative as scientists to do what we can to propagate the truth and help others overcome ignorance and misinformation. There are some dark times approaching for science in general, but it is our job to stand up for it at every opportunity.