Have you ever heard the phrase, “socialism sounds good in theory, but it fails in practice?” As any in depth reading of the 20th century will show, the latter charge is evidently true. However, socialism, and centralized economies in general, also have a fundamental theoretical issue that many of its proponents fail to take seriously.

Have you ever considered how we determine the price of everything we buy? I feel comfortable assuming that you haven’t, and in full disclosure I hadn’t either until very recently. But it's a question that warrants some deliberation. Let’s explore:

Firstly, the price of one thing kind of depends on the price of everything else. For example, the price of a laptop depends on the price of each of the components that go into it; and the prices of those components are dependent on the price of the labor that goes into mining and collecting the resources those parts are made of; and the price of that labor depends on a near infinite number of factors, all of which must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis that takes into consideration differences in people talents, abilities, and interests. Further, one must also consider more subtle factors such as climate, geography, culture, and politics, all of which indirectly affect something’s price. And I won’t even begin to talk about the risks that entrepreneurs take when pursuing business ventures, because trying to assign a monetary value to risk is impossible irrespective of the special circumstances of a particular situation.

Not only must a supplier calculate the costs incurred and risks associated with bringing a final product to market, but he must also negotiate with consumers – because entrepreneurs will only turn a profit if their product sells; and in order for it to sell customers must be willing to pay the cost; and for that to happen consumers must believe that the benefits they receive will outweigh the costs incurred from purchasing it.

So how exactly do we account for all of those relevant factors and come to an agreement on what something is worth? Doing so for one product appears hard enough, but just imagine trying to do that for every single good and service that gets exchanged. Then imagine trying to do that every single day – because prices of capital products change on a day-to-day basis.

This is called combinatorial explosion, and it’s a fundamental problem with computing. When trying to determine something’s worth, the number of combinations that one has to examine grows exponentially, so fast that even the most powerful computers we have will require an intolerable amount of time to examine them. Exacerbating the problem of combinatorial explosion is the fact that what constitutes value itself is highly subjective. Perhaps you’d be willing to pay more for a hybrid than a pickup truck if you have a job that requires you to commute; and perhaps the opposite would be true if you own a landscaping company. Regardless of what example we use, its obvious that some people value some things more and some things less, and thus you can’t assign definitive monetary value to a product without regard to individuals tastes and preferences – in other words, you need feedback.

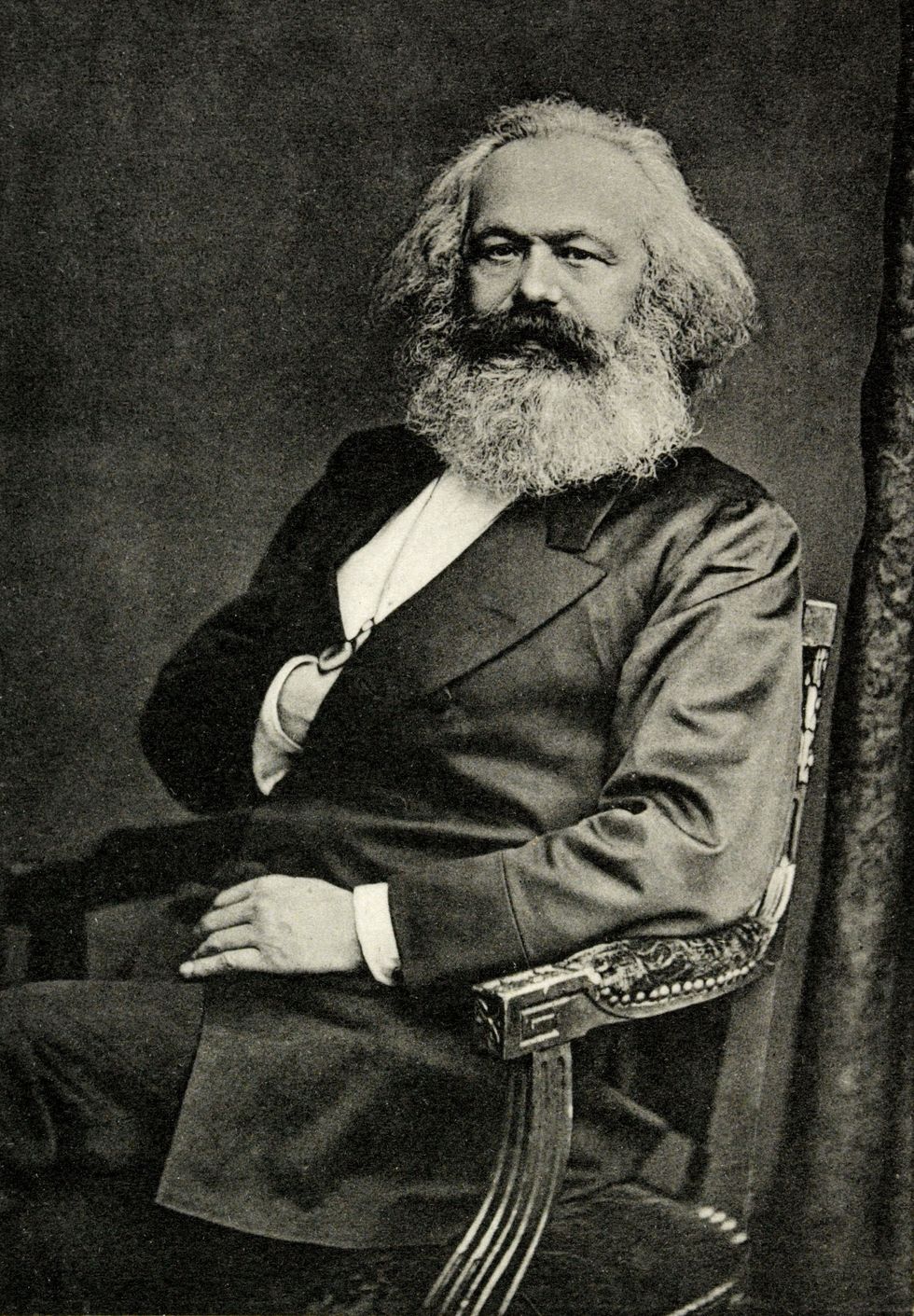

Although price calculation is an irreducibly complex problem, it’s one that needs to be solved – and from a purely theoretical standpoint, it’s one that socialism fails to address. Ludwig von Misses elaborated on this idea in his workEconomic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth. His critique of socialism, popularly known as the Impossibility Thesis, goes as follows:

The very definition of Socialism is that all the means of production belong to the government. Spin it any way you want to, that they belong to everybody, or to nobody, or to the government, but the important point is that there is no buying and selling of means of production. Nobody can buy or sell steel or coal or a factory, because it is illegal for anyone to own them. That would be Capitalism, if a private person owned any means of production whatsoever and could do with it as he pleased.

So, socialism abolishes private property of capital goods and natural resources. Since the socialist State is sole owner of the material factors of production, they can no longer be exchanged. Without exchange there can be no feedback and hence no market prices. Without market prices, the State cannot calculate the cost of production for the goods it produces. In the absence of economic calculation of profit and loss, socialist planners cannot know the most valuable uses of scarce resources – thereby making the socialist economy, from a theoretical perspective, strictly impossible.

So how have we solved this problem? Obviously there is some phenomenon that works as a price calculator otherwise we wouldn’t have prices.

Well, herein lies the genius of market systems: they provide a distributive computational solution to the problem of overwhelming combinatorial complexity. Because no single person can account for all of the relevant factors that affect prices, the only solution is to leave people free to figure it out on their own. Here is a more technical analysis of how this works:

All people make monetary bids for goods according to their subjective valuations, leading to the emergence of objective monetary exchange ratios, which relate the values of all consumer goods to one another. Entrepreneurs seeking to maximize monetary profit bid against one another to acquire the services of the productive factors currently available and owned by these same consumers.

In this competitive process, each and every type of productive service is objectively appraised in monetary terms according to its ultimate contribution to the production of consumer goods. There thus comes into being the market’s monetary price structure, a genuinely “social” phenomenon in which every unit of exchangeable goods and services is assigned a socially significant cardinal number and which has its roots in the minds of every single member of society yet must forever transcend the contribution of the individual human mind.

So, rather than being set by an arbitrary authority from the top-down, contrary to what advocates of socialism might argue, prices actually emerge out of a collective process of people making individual value judgments and price appraisals from the bottom-up – and in effect, markets act as a de-facto price calculator by facilitating exchanges of goods and services between individuals.

Now I would be remiss if I didn’t admit that markets have issues, and of course our free enterprise system doesn't always live up to our highest expectations. However, when examining issues of the economic variety, one must always stay grounded in reality. Obviously if you use some hypothetical utopia or dreamland that has never existed as the basis for comparison our society will certainly fall short; but when compared to other societies, historical and present, we stack up among the best in the world.

Further, so long as we grant people the liberty to make their own choices, inequities will always exist; and as a consequence there will always be some people who are less well off than we would like. This doesn't mean we should do nothing to help those people who fall through the cracks, and it doesn't mean that all socialists are cranks. What it does mean, however, is that we shouldn’t strive for perfection in the form of a socialist utopia – because once you understand that the world is incomprehensibly complex, that humans are imperfect and imperfect creatures cannot produce something perfect, you come to understand what an absolute miracle it is that our society functions as well as it does.

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion