Hello there! Have you ever been walking along, minding your own business, when out of nowhere you see a girl in a short polka-dotted skirt, colored tights, shoes from the 1950’s and eyes with galaxies hidden in them suddenly burst into song while dancing in a sudden rain shower with a reserved, buttoned-up male who looks confused and yet totally enchanted? If you have, congrats! You’ve witnessed a real, genuine Manic Pixie Dream Girl sighting.

For those of you who perhaps aren’t familiar with this term, I’ll back track. According to the most popular definition on Urban Dictionary, a Manic Pixie Dream Girl is, “a term coined by film critic Nathan Rabin after seeing 'Elizabethtown'. It refers to ‘that bubbly, shallow cinematic creature that exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.’ A pretty, outgoing, whacky female romantic lead whose sole purpose is to help broody male characters lighten up and enjoy their lives.”

In other words, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (or MPDG as I’ll be referring to her for the rest of the article) is that one character you’ll see cropping up all over fiction of all kinds these days, the quirky, dreamy-eyed, red-lipped nightmare who simultaneously builds up the main protagonist’s life by freeing his spirit and destroys some main aspect of it by eventually leaving him or wrecking his carefully structured life plan. The MPDG makes most of her appearances in various forms of indie romantic dramedies, teen literature and student films. And while it’s easy to look at this obvious stereotype and chuckle, there’s a dark side to the idea of this life-changing ray of sunshine that has led me to become more and more disgusted by it as the years go by. One of the main problems? She has no agency.

As the creator of the term, Nathan Rabin, pointed out, this is a character who exists almost completely to serve another character’s developmental arc. In fact, the male protagonists who play opposite the MPDG often wouldn’t even have an arc of any kind if it weren’t for her presence. All of their change, all of their growth, every lesson they learn from the beginning to the end of their fictional adventures, depends on them meeting this girl, this wonderful, life-changing girl whose only flaw is that she’s impossible to tie down, a fact that always seems to make her just a little more irresistible to her determined admirers.

While the MPDG may be graced with a little bit of back story, such as a sad home life, a series of failed romances, or some other kind of tragedy that partially explains away her flighty nature, this information only exists in order to justify her behavior when related to the male protagonist. We never learn anything about the MPDG that makes us connect with her as a character outside of her relationship with her beau. Everything is put in the context of their romantic fling. The MPDG never acts as though she has any concrete life goals, a motivation that is driving her forward, or a sense of purpose outside her defining relationship with this man. Her only fulfilling job or project in life is evidently to make her lover a more well-rounded, happier human being. Until such time, of course, as she inevitably remembers her desire to roam free and cuts all ties with him in a sudden, dramatic, usually distinctly unpleasant fashion.

It’s not hard to point out the reasons this would be a harmful performance for both men and women to witness. Not only do the MPDG and male lead clearly have a co-dependent and unhealthy relationship, but seeing a woman whose only purpose as a character is to prop up the flatness of the usually stiff-necked drag she finds herself entangled with only speaks to the fact that the people who write or appreciate this character are seeing women themselves as objects. Contrary to popular belief, it is more than possible to objectify a woman without ever making a concrete comment about her physical appearance. By indicating that this oh-so-desirable woman is loved merely because she is a tool for this man to use to feel better about himself indicates something horrible about the way we as a culture look at women in romantic relationships in general. Too many times in my very real relationships outside the realm of fiction, I have felt pressured to play the MPDG. I have felt the expectations of men who wanted me to be the answer to a question they weren’t even sure how to word. As someone who always has the (sometimes unhealthy) desire to fix whatever is broken, I have had to learn how not to be used, how to be on my guard for those who see me only as a concept instead of living, breathing human being.

The MPDG is not a living, breathing human being and has no business representing one. The MPDG has no major flaws, and is a constant support for those who need her, but never in need of support herself. She is a fantasy walking around in flats and a cute little hair bow, but not a harmless one. In real life, a MPDG would exhibit many signs of being very emotionally damaged and unable to keep up any kind of healthy relationship. There’s nothing wrong with writing a character who has those traits, but praising those qualities and setting up that example of stunted emotional growth in women as a recipe for becoming the “dream girl” of thousands of men is very disturbing.

It’s worth noting that there have been multiple occasions where myself or friends of mine have been called Manic Pixie Dream Girls, whether as a joke or in all seriousness. I will admit here, with total honesty, that I do share some traits of the stereotypical MPDG. I am fairly literary, which is sometimes a trait exhibited by these types in fiction, I do like some off-the-wall things, I do prefer a vintage style of dress when I can afford it, and I don’t always have a plan. I tend to fly by the seat of my pants and I do love making up adventures for myself and those around me whenever possible. However, none of these things makes me particularly special or anything resembling the MPDG you might see when you flip through the nearest hipster’s debut novel. I have very real flaws. I can be gross and silly and sweet and angry and unfair and sensational and sad and funny and petty. I am not defined by just one thing, or even a handful of carefully selected moods or pieces of clothing or personality traits. I am not a Manic Pixie Dream Girl. I’m a woman, who likes a range of things, who engages in a plethora of different activities, and who has many different sides and emotional responses to what goes on around me. The problem with the MPDG is that she is defined by what in real people would be viewed as one facet of their personality, one millisecond in the flash that is their lifespan. Expecting a flesh and blood human being to behave like the MPDG is to neuter the beautiful complexity of the human experience, the shocking and intriguing masquerade of emotional responses and physical encounters we partake in every day.

Of course, I’m hardly the first person to say this, and I’m sure I won’t be the last, but the Manic Pixie Dream Girl has got to go. We have to stop writing women into boxes like this, using them as tools in fiction instead of insisting they be developed into real, defined characters. We have to break free of these outdated ideas, of these carefully structured scripts for behavior that have been forced on us by traditions in entertainment and the world in the past, and begin to see people as they are, as complex and confusing humans who all have a voice, all have a soul, all have a purpose. As a content creator I can’t stress enough the importance of writing characters like that, characters who may not be good, but who are always, always human—in-depth, well-rounded humans, regardless of their gender.

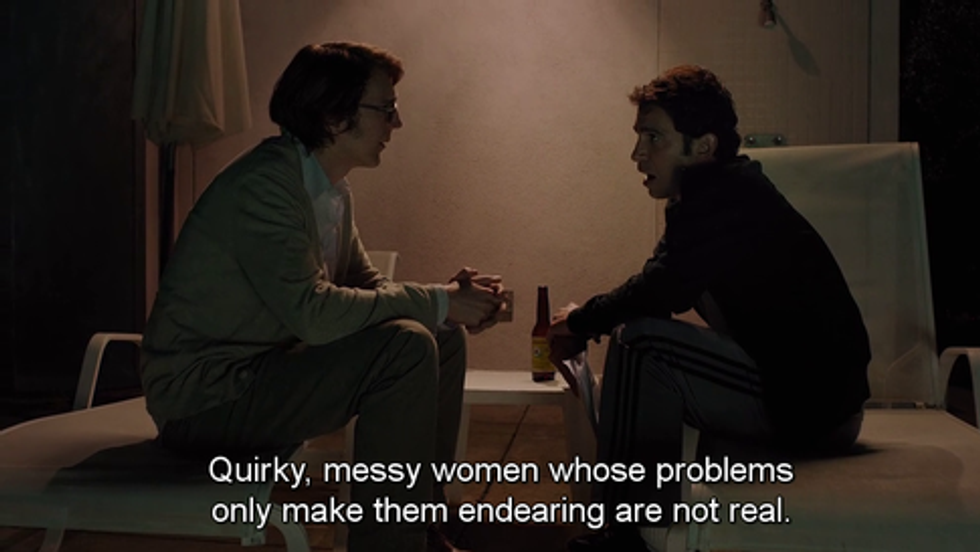

Some writers have gone on to parody the idea of the MPDG, only to expose the sham of it in the harsh light of day. However, if you ever switch on your TV or pick up a book and experience your first or second or one-hundredth honest-to-goodness MPDG sighting, I beg of you, recognize that character for what she is, a misshapen, haphazard tool someone is trying to use to tell a story that is far more twisted than it may seem. Let us see these characters not as an ideal to strive for, but a warning against not only the influence and power of all fiction, but the harm it can cause when the fiction we write portrays the unhealthiest mindsets of our society.