Inside kitchens and various quarters scattered across powerful American universities lived enslaved African Americans whose contributions have remained largely untold and long ignored. Recently, dozens of American colleges have taken steps towards reconciling with their direct roles in the perpetuation of racial bondage and put forth efforts to recognize the contributions of enslaved individuals of that time. Wealth accumulated from the institution of slavery and related industries (labor, slave sales, trade, etc.) was instrumental in the funding of America’s most prestigious universities including Harvard, Princeton, Columbia, and Yale.

Not surprisingly, many universities in the south such as Vanderbilt, University of Mississippi, University of Alabama, and the flagship school of Texas — The University of Texas at Austin — have a history marked with the exploitation of human labor.

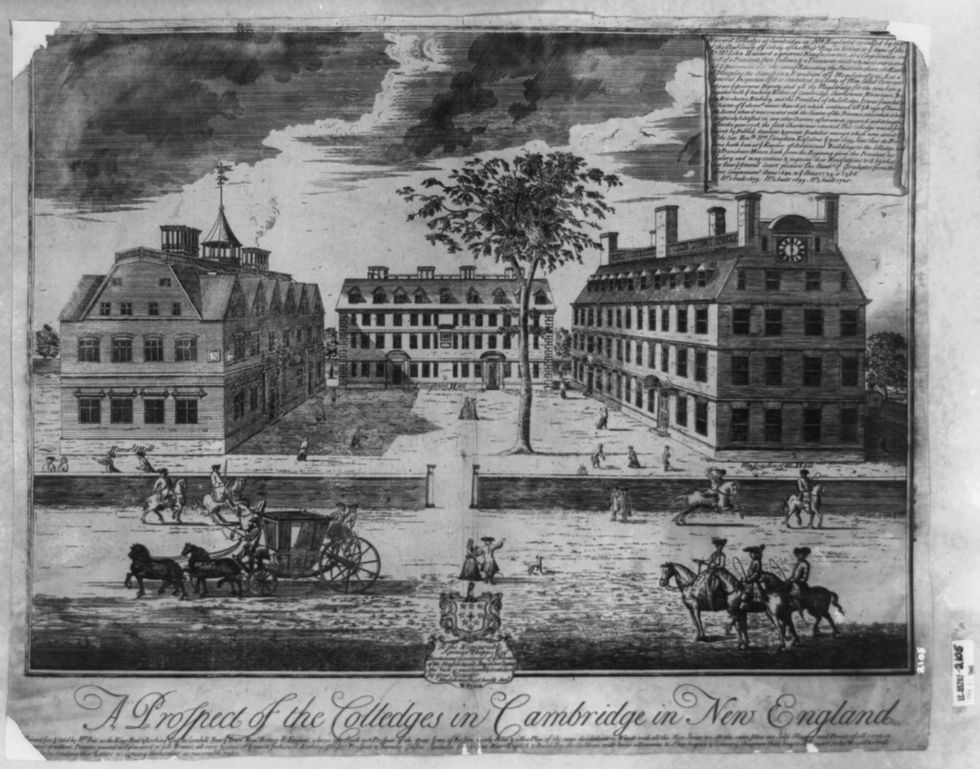

“Throughout the Mid-Atlantic and New England, higher education had its greatest period of expansion as the African slave trade peaked. Human slavery was the precondition for the rise of higher education in the Americas,” says Craig Steven Wilder, a historian at and author of "Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America's Universities.”

The perception illustrated of the United States prior to the Civil War is that the North was free of slavery while the South indulged in a very harsh system of slavery. Though this is correct in some senses and the two regions would go on to engage in war against each other over issues related to slavery, the North’s involvement in slavery exceeds the oversimplified story that is often told in classrooms. For example, in the 18th century there were over 100,000 slaves accounted for in Northern territories alone; America’s prestigious universities also accumulated their wealth from the institution of slavery.

Outside of the physical presence of slaves on college campuses, many colleges perpetuated the institution of slavery through accepting money from benefactors whom accumulated their wealth off the backs of slaves. For instance, early benefactors who donated money to Brown and Harvard built their fortunes by sending slave ships to Africa and milling cotton from Southern plantations. By virtue of the unpaid labor of Jesuit-owned slaves on plantations in Maryland, Georgetown could afford to offer free tuition to its earliest students. Dartmouth housed more slaves than faculty and administrators; in fact, “there were as many enslaved black people on Dartmouth’s campus as there were students in any given classroom” (Wilder, 2013). And at Thomas Jefferson’s University of Virginia, slaves cooked and cleaned for students – and even lived in the kitchens.

The University of Texas at Austin was recently confronted with their history during an effort to take down confederate statues around campus that were originally erected to uphold the “Southern perspective of American history” as required by Major George Washington Littlefield in exchange for his generous monetary donations, but taking a deeper look at Major George Washington Littlefield, it can be seen that a portion of his wealth was a result of the vast plantations he owned in New Mexico and Texas.

The university voted to take down the statues in light of nationwide efforts to de-memorialize the Confederacy due to its contemporary connection to modern white supremacy and neo-Nazism.

Universities and preparatory schools alike were built using money and labor acquired through the exploitation of African American labor. Because of this, education was able to flourish and effectively advance white society; yet, the descendants of slaves are among the most underrepresented on college campuses today. Low income blacks tend to be the descendants of American slaves who suffered from generations of racial oppression- from the middle passage, to slavery to Jim Crow and to the current system of mass incarceration.

And, according to The Journal of Black in Higher Education, they are not the students benefiting from today’s inclusive admissions programs at America’s most selective colleges. It is ironic that, though African American slaves built, tended to, and helped finance the country’s most elite universities, their great grandchildren and beyond are not able to reap any of the benefits.

Addressing the distressing realities of America’s racial past is important because, in order to truly move beyond injustices fundamentally, we must fully acknowledge our history – and America’s history of slavery and its subsequent trauma is often ignored. Also, understanding this history will lead to better understandings of the attitudes and assumptions that made the oppressions of slavery possible in order to overcome the residue still present today.

As Drew Gilpin Faust of Harvard university said, “If we can better understand how oppression and exploitation could seem commonplace to so many of those who built Harvard, we may better equip ourselves to combat our own shortcomings and to advance justice and equality in our own time. At its heart, this endeavor must be about 'Veritas,' about developing a clear-sighted view of our past that can enable us to create a better future.

The past never dies or disappears. It continues to shape us in ways we should not try to erase or ignore. In more fully acknowledging our history, Harvard must do its part to undermine the legacies of race and slavery that continue to divide our nation.”