The only reason I know the name Sister Rosetta Tharpe is because she appears for a second in a scene from one of my favorite movies called "Amélie." I was so intrigued by the way Tharpe sang and played the guitar in that second-long scene (I had honestly never seen anything like it), that I was motivated enough to figure out who she was. In retrospect, I find it a little disheartening that I found out about Tharpe this way, because there are plenty of other reasons why I should have already known about her.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe was born in Arkansas in 1915 to a musical father and very passionately religious mother. Tharpe's mother, Katie Bell, left her father when she was just a little girl to continue a more religious lifestyle up north. It was around this time that Katie Bell started to encourage her daughter to practice music.

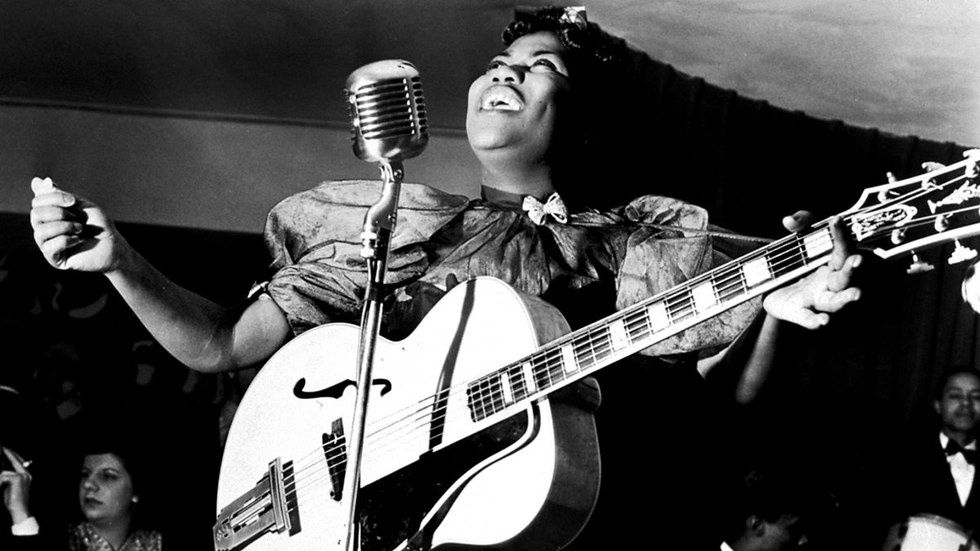

By the age of 4, Tharpe was already singing and playing guitar for the church(es) her mother was a part of. By the age of just 10, Tharp could play the guitar, piano, sing and dance, always putting on a lively show for the church congregation. As years went on, Tharpe began to develop a kind of talent and passion for music that nobody had ever seen. One member of a Philadelphia church that Tharpe used to perform at recalls, “She would look up while she was performing ... as if God was in her and she was communicating with Him rather than with a human being.”

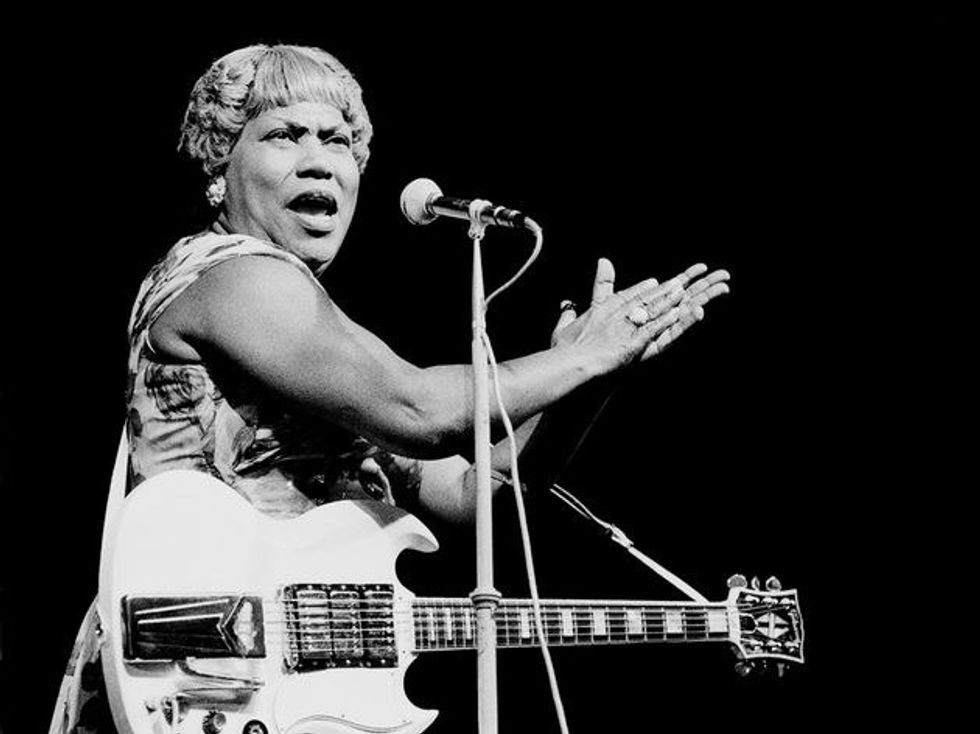

“She could play a guitar like nobody. Nobody!” says Lottie Henry of the Rosettes on a PBS program called "American Masters." So, why does it seem as though her name has been forgotten throughout the history of rock n’ roll? Tharpe’s early rock and gospel music greatly influenced huge artists like Chuck Berry, Elvis, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lewis, and even Buddy Holly. Biographer Gayle Wald says, “She had a major impact on Elvis Presley ... It’s not an image you think about when you think of rock n’ roll history. You don’t think about the Black woman behind the white man.” In fact, when Johnny Cash was being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, he said Tharpe was one of his favorite singers as a child. Unsurprisingly, Tharpe does not yet have her own place in the Hall of Fame. Her influence has been strewn through decades of rock music, yet Elvis seems to be the only name people remember when it comes to pinpointing the start of this genre. Believe it or not, the King of Rock was far from being the first person to shock an audience with an electric guitar.

Tharpe moved to New York City in 1938, following her first divorce, with her mother and sister, where the three women would spend late nights singing songs together, which often ended in tears. Her sister recalls, “We didn’t know where we were going from there.” But this certainly did not stop Tharpe from continuing her career. She was known for her shows at Harlem’s famous Cotton Club, where the majority of the audience was white and the setting was no longer religious. Although some people were unsure of her shift towards a more secular lifestyle, her devotion to God never dulled, and her passion for gospel and rock music only grew from there on. She was someone who was having the nerve “reinterpret a spiritual song for a secular audience. I also think she was just rebellious” (Wald). As a result, she was attracting a larger audience and getting requests from bands her wanted her to be a part of their music.

During WWII, segregated black soldiers claimed Tharpe as one of their own. She would sing to them over the radio and dedicated songs to specific soldiers. She performed for average people: “She performed for people who worked — people who were trying to better themselves — this music was their inspiration. There were lines three and four times around the block [for her shows],” says Ira Tucker Jr., son of the Dixie Hummingbirds’ band leader, “Rosetta had a one-on-one with everybody, because she could make that guitar talk like you were there with her — like you helped her write the song.”

But despite her enormous fame at the time, “she was still Black,” and a woman, so when she went on tour with white bands like the Jordanaires, there were often times when she wouldn’t be able to walk into the same restaurant, so someone had to bring leftovers back for her to eat on the bus. Sometimes, people would serve them out the backdoor, but they still had to take it back to the bus. Perhaps it is for this same reason that her name has been lost among so many other names of white (and even Black) male rock stars, despite being one of the best early rock and gospel musicians the world has ever seen.

I hope that one day, Tharpe's musical influence and achievements are recognized to the extent that they ought to be and she is given a rightful place in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. She may have technically been a gospel artist, but her style was so uniquely her own, that she was able to heavily influence other artists like Elvis — "The King of Rock 'n' Roll." If it weren't for Tharpe, who knows if Elvis himself might have taken a different approach to rock music.