Since the news first covered Russian government–sponsored interference and hacking in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, reporters and experts been working toward uncovering the full extent of the regime’s cyber activities, both in foreign and domestic media. Although Putin may deny the allegations, it’s pretty much an open secret by now that Russia’s been utilizing armies of internet trolls and threats to media companies among other methods to retain power. Even then, some of the most trafficked platforms and websites in the world—Facebook, Google, Twitter—are still accessible in Russia. Presumably, the regime keeps these outlets open for the same reason it still holds elections—to have the legal credibility to deny allegations of an authoritarian state.

The Chinese government on the other hand has never been one for pretenses. The Great Firewall of China is a full censorship apparatus that has no qualms about banning the same popular platforms and websites that remain available in Russia. Back in 2000, it took shape in the Golden Shield Project, a surveillance system meant to allow China to reap the benefits of Western technology while barring the Western ideas it would make available. Former president Jiang Zemin saw the system put into place, and his successors saw it strengthened and expanded until Xi Jinping took up the reins in 2013 and decided to go full dictatorial on China.

Under the guise of safeguarding China’s “cyberspace sovereignty,” Jinping’s regime has been putting into place new measures that require internet services to undergo a security review, if they may affect national security, and strengthen requirements for internet companies to “censor content, shut down their services, register their users’ real names, and provide security agencies with user data stored in mainland China.” By virtue of China being a massive export market, technology companies have been willing to appease the government as to sell their product there.

To help filter information and gather data on users, China’s telecommunications and systems companies, such as Huawei and ZTE, have developed complex information controls—technology that has been exported to countries around the world, including Russia. These controls have helped China expand its censorship apparatus into every nook and cranny of the internet where its citizens may interact with one another.

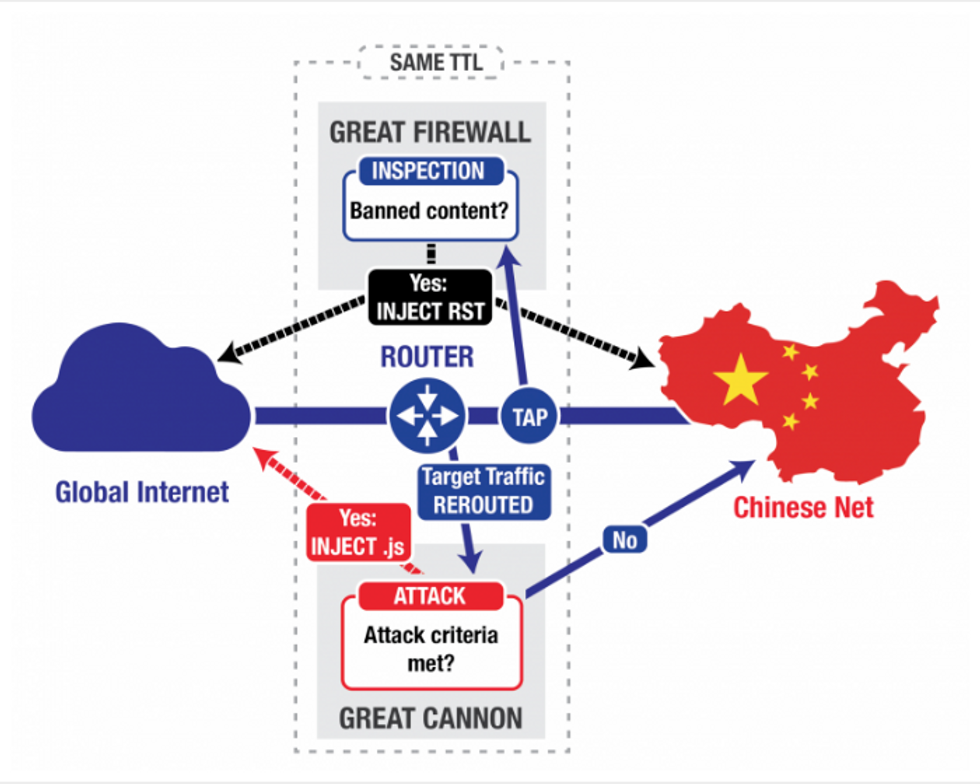

In September, Xi Jinping’s regime reached into private online chat groups, slapping users with legal responsibilities and rating systems that judge the content shared in these groups. And the government targeted Virtual Private Networks (VPN), which have been utilized in the past by citizens to access banned sites. And if an online or messaging service hasn’t been cowed into obedience to China’s digital media rules, the regime can just utilize classic disruption tactics such as the denial–of–service attack (DoS). The Chinese have a particular variant known as the “Great Cannon” for use against foreign websites.

With bypasses like the VPNs closed, with anonymity stripped through real–name registration, with bannings and disruptions to popular websites, Chinese citizens have found themselves ever more isolated from the broader community of users and content on the internet. Xi Jinping’s reign has seen the Great Firewall reinforced to counteract the supposed democratizing effect inherent in new media. Once the wall is completed, once the avenues to information outside China’s censors are cut off, once the citizens are kept under constant monitor on their devices, it will be the same as having no internet at all, as in North Korea.

Even as the government pushes an open door policy toward foreign customers and other nations, it keeps a closed door policy on its online realm. With the aid of its technological advancements, China has developed the means of achieving complete authoritarianism.