Warning: The analysis of the following game does contain disturbing imagery taken from the game itself. While not explicitly inappropriate, reader discretion is advised.

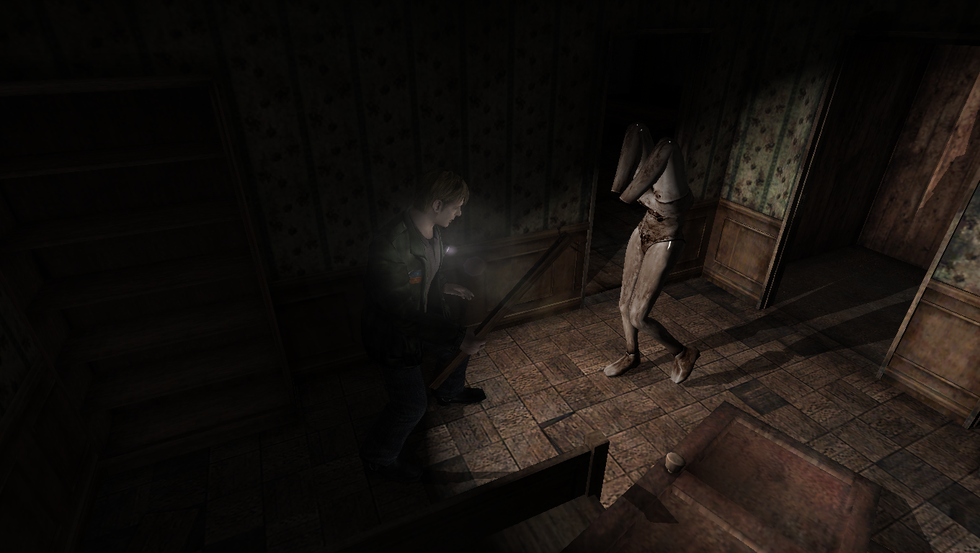

One of the key aspects of video games that make them so effective in the horror genre is their ability to immerse the player within the fictional world of a game. While the player interacts with the artificial space, he or she is drawn into the fantasy, making him or her more subject to scares. Yet for as frightening as it is, the real brilliance of "Silent Hill 2" doesn’t merely stem from how frightening it is.

What gives "Silent Hill 2" its psychological edge as a horror game is its utilization of expectation and subversion. Horror, much like comedy, is based on the subversion of expectation. When something fails to match up nicely with our expectations, we are left with the unsettling space between, the uncanny. "Silent Hill 2" thrives on this unbalance, and by keeping the player constantly on-edge between the expectation and the reality of a thing, the horror of the game is made prominent.

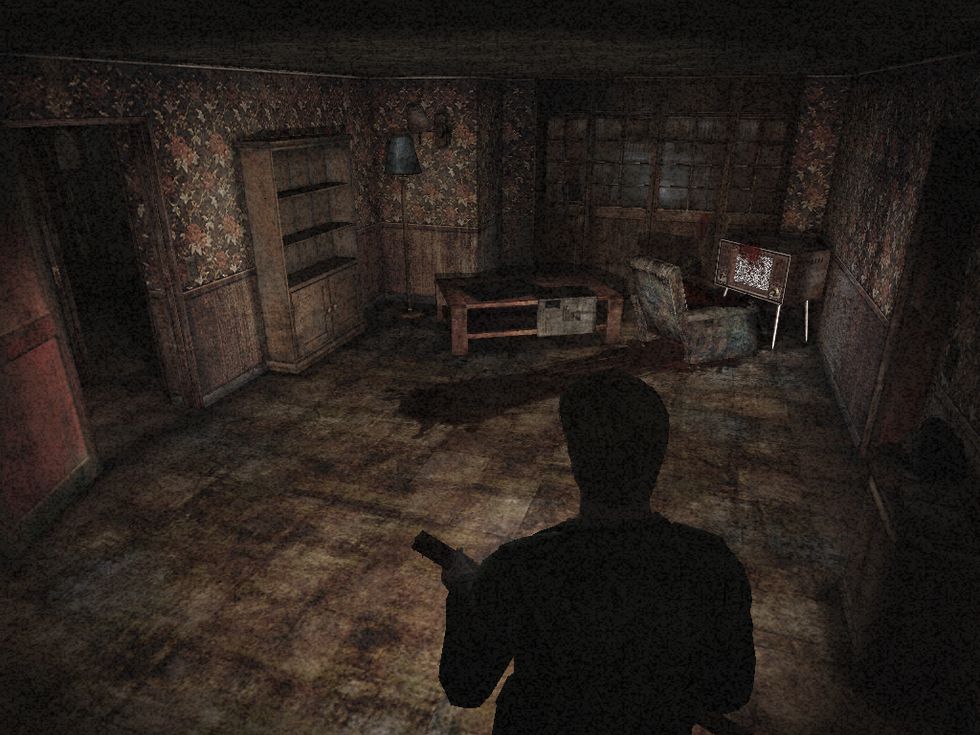

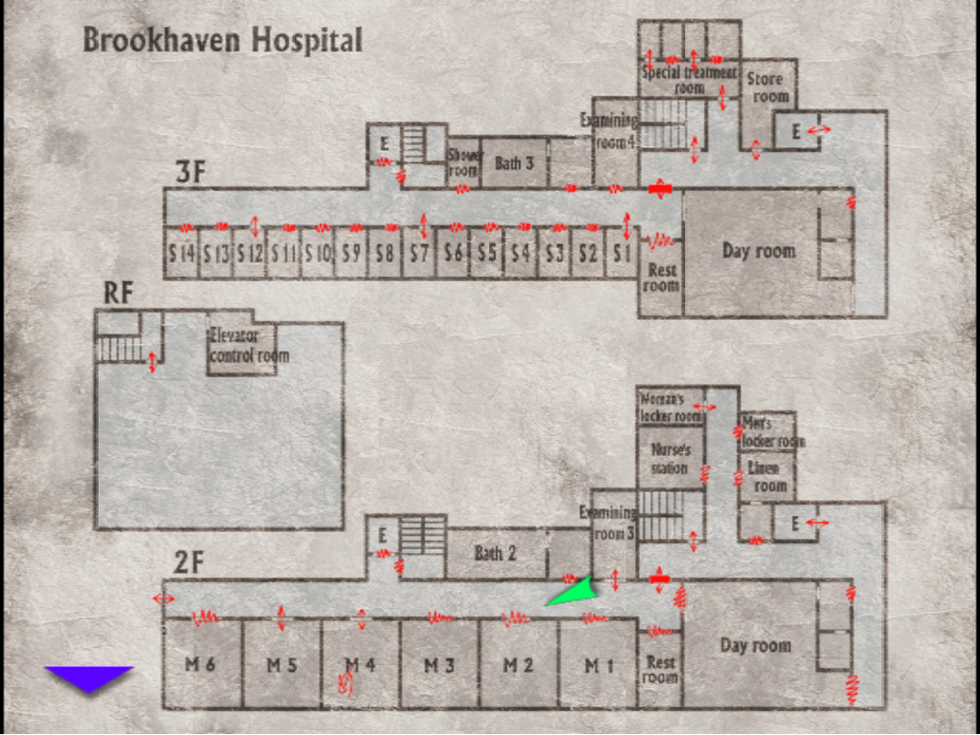

The level design provides us with a wonderful example. All of the locations throughout the game are based on orderly structures, like apartments or hospitals. They follow a general logic in terms of layout. However, the player is unable to access many of the rooms on a floor, frequently reducing the apparent order to a functionally asymmetric mess.

Pictured: One of the maps from Silent Hill 2.

Of course, things don't stop there. The internal logic of each room is often off-putting. Furniture-less apartments, artificial walls, and secret passages all defy the orderly structure of a location promised by the initial blueprints you pick up in an area. What naturally develops from this gradual deconstruction of order is a slow descent into paranoia and fear. Any new area in "Silent Hill 2" initially promises order and coherence; however, this idea is quickly stripped away to reveal a far more confusing and upsetting reality.

On that note, let’s talk about the act of descending in the game. The game starts with the main character, James Sunderland, overlooking the entire town of Silent Hill. This frames our expectations for the journey ahead. As James descends into the town, he descends into his own psyche. A strangle disproportionate amount of time in "Silent Hill 2" is spent going down. From the long initial trek into the town from James’s parked car to the seemingly endless stairway hidden away in the Silent Hill Historical Society, James is constantly moving in a downward direction.

The significance of the constant descent and the internally inconsistent environments is two-fold. On one level, it ties directly into the "Silent Hill 2" narrative (which is far too clever for me to spoil here); suffice it to say, there’s a reason we’re trekking ever deeper in the dark recesses of James Sunderland’s guilt-ridden mind. The other reason for this structure is, once again, the subversion of expectation. The amount of time spent descending is, from a purely logical standpoint, impossible. Multiple times in the game, James should have no point lower to descend to, and yet, in the surreal world of "Silent Hill," such a descent is entirely possible.