This past December, I had the opportunity to volunteer at the Rohingya settlement in New Delhi. As much as the daily news coverage regarding Rohingyas makes our hearts bleed for the countless who lose their lives, the experience of working in close proximity with Rohingya refugees was an astonishingly different experience. Sharam Vihar is a suburban locality in the periphery of New Delhi. The enclave (more of a shanty), houses 94 Rohingya families and approximately 500 IDPs (Internally Displaced Peoples) from within India. These IDPs come from different states from India and are mostly devout Muslims. Thus, one could label Shram Vihar as a Muslim shantytown, in an otherwise exceedingly Hindu dominated country.

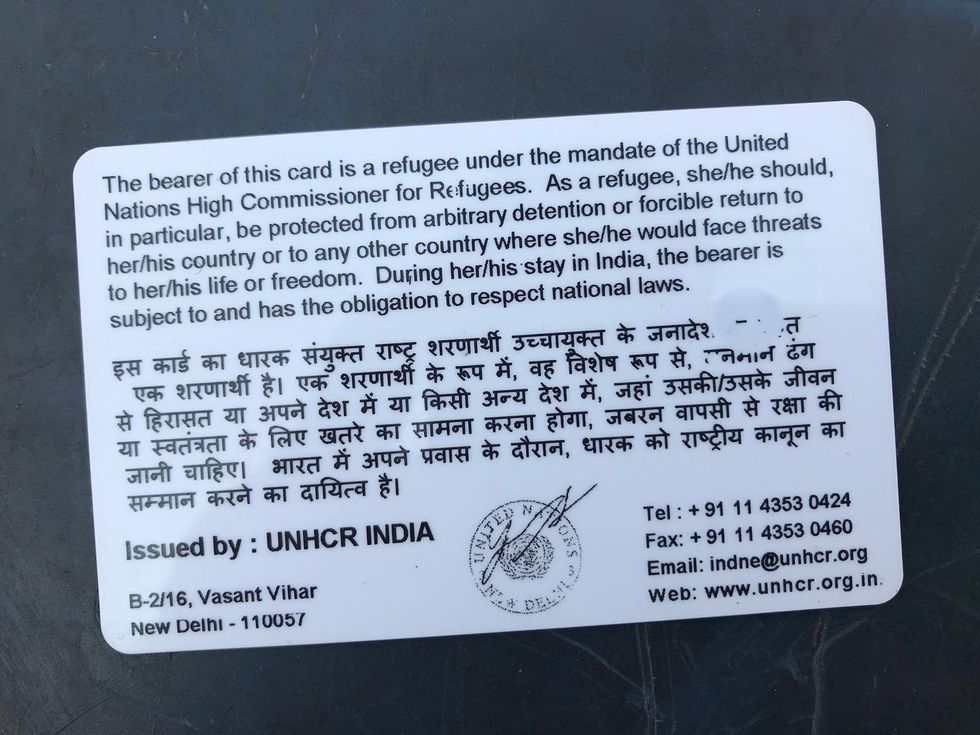

Each of the Rohingya families has been conferred a refugee status by the UNHCR (The UN Refugee Agency). The refugee card helps them access major dispensaries and the multi-specialty Safdarjung hospital, in case of any medical emergency. All of them remain grateful to the Indian government for sheltering them, yet they have desires to go back to their “Watan” (a Hindi/Urdu word meaning ‘Country’).

Most philanthropists make donations or bring in aid in the name of the Rohingya community. As a result, there has been a relatively suppressed personal scuffle between the IDPs and Rohingyas. It is recognized that, after the mass exodus on August 25 and the Supreme Court’s decision to deport Rohingyas, a sizable number of Rohingya daily wage workers face trouble finding work. However, the reality rests in the fact that most Rohingya refugees do not need to scrounge for work at all. Most Rohingya houses have a surplus of rations and other essentials such as sanitary pads, toiletries etc. Rohingya families usually go out to the market and sell the excess resources in the market. This stokes the brawl between Rohingyas and the rest of the slum dwellers as Rohingyas are increasingly being viewed as the entitled sect in the shanty.

On my first visit to the camp, I was strolling around the camp, hankering after middle-aged Rohingya people to talk to. Surprisingly, the only people who spoke to me were all men. Even the younger lot just comprised of a crew of teenage boys who were donning skullcaps. While a ‘self-proclaimed’ local leader told me harrowing stories of migration from Myanmar to India, the kids told me about how they withdrew out of the local school and were attending classes at a Madrassa (Islamic School). Some of the young kids attend government schools, though the general Rohingya participation in schools remains abysmally low.

On one of my visits to the camp, I visited a makeshift school run solely by a magnanimous individual named Mr. Anas (The Guncha Foundation). His initial intentions were to rope in Rohingya kids and further their education. Ironically, Rohingyas refused to let their kids mingle with any other local communities. No other breed of Muslims, let alone any Hindu! In fact, on one visit, a Rohingya leader vocalized his ardent belief in confining his women within the house (upon reaching puberty). Thus, most Rohingya girls are out of school, palmed off as young and tender child brides. This deep-seated, conservative thought process, pervasive in the Rohingya brethren has caused persistent brawls in Shram Vihar.

While the world is condemning the mass atrocities committed against the Rohingya community, what I learned from my time as a volunteer at the camps was that one must not buy what the media touts. Just because the Rohingyas are experiencing the gravest of human rights violations does not mean every section of them suffers equally. The diaspora in New Delhi has a decently dignified and a ‘not completely’ deprived lifestyle.

Obviously, it is undeniable that there is much more that the Indian government must do to uplift the social and economic status of Rohingyas. Permanent housing must be provided, the deportation order must stay, there MUST be concerted efforts to facilitate higher education among Rohingya kids who were uprooted from Myanmar while enrolled in colleges, etc.

Having said that, no matter how much the community collaborates to restore the status of the inhabitants of the slum, no amount of external effort or monetary support can fill in the voids of filial separation that Rohingyas go through. The emotional turmoil of being away from their motherland and a consistent fear of the safety of those left behind perpetually lurks over.