The potholes jostle my things and I use my hand to steady them. Wafts of maple syrup travel their way from the small hands of the boy three rows in front of me, remnants from the breakfast we had four towns back. I watch as his mother attempts to gather his fingers, trapping them like fireflies in her cupped hands. Smiling and wiggling in his oversized, brown leather seat, the smell of the sleeping man’s cologne meanders its way back to me, clashing with the sweet syrup.

Another pothole and I swat my hand back to steady my plaid suitcase, scarred and branded by pencil markings and coffee stains. Remnants of trips packed away in photo albums. The driver, a portly many with fiery red hair and a clean shaven face slows the Greyhound to a stop, though not before hitting another pothole. The flashing lights of an oncoming train blink and the guardrail slowly descends. Slouching in his chair, tired from the long ride and waiting for the freight train to pass, the driver begins to shuffle through a collection of cassettes tucked away in the console beside his well-worn chair. He contemplates between a dark blue with white block lettering and a puzzle of hand-drawn wildflowers. He chooses the flowers, wilting at the edges with overwatering, and gently loads it into the player.

The round, coffee-stained speakers at the base of the mud-speckled windows crackle to life. The voice of a young woman swells with the oncoming train, both competing for an ear. As the train rumbles past, the woman sings of a small town she has left in her rearview mirror and the big neon lights of adventure coming into focus ahead.

Though the tumbling, iron wheels of the train and the crescendoing voice on the spinning tape reels compete for my listening ear, I can only hear the turning record in my empty room at the end of the wood-paneled hallway, perpetually leaking the smells of a cedar forest. While the cologne overtakes the swells of syrup, I only smell the musty record covers propped against my nightstand lamp. One of the veteraned originals from the labyrinth of records that once resided in my Dad’s nightstand. The record turns and I hear the voices of men and women I have never met but are ingrained into my memory like the faces of my family. They sing of love and loss, happiness and sadness, grief and revival. They are voices not heard since childhood, but they feel as familiar to me as the name I carry.

Though I grip onto my rigid bus pass, the music of a familiar voice echoes against my empty room and I slowly begin to feel her warm hands slipping into mine. They are small like I remember and warm as when we used to sing and dance along with the voices from Dad’s nightstand.

The revving of the bus engine jolts me from my memory. We pass the tracks and the women sings of her first night in a big city. Lights swish by my window as dusk turns to dark and the woman sings of the neon lights swishing by her window too. The lights reflect off of my journal cover, though the reflections become less frequent as we drift down the dark highway.

The record still plays and the pistons still fire in the bus engine and I still hear the record turning, though I know the sound must no longer emanate in that empty room.

The red-headed driver changes cassettes and I gaze over at a boy who would have been the same age as her now, swaying ever so slightly with each rotation of the bus wheels. A man’s deep voice floods the space and the driver pounces on the volume knob, sheepishly turning the knob until the man’s voice is no more than a whisper in the dark. I let myself close my eyes and I feel her hands in mine again. Laughter echoes in my ears, our laughter. I see her smile, as warm as the sun hitting our backs from Mom and Dad’s bedroom window as we hungrily search through Dad’s records, hoping to stumble upon one we hadn’t heard yet. I feel the fog tingling my ankles walking back from the record store, a new voice in my bag and a new roll of wrapping paper in my hand. A gift for her.

I’m awoken by the deceleration of the bus, instinctively grabbing onto my things in the seat beside me. We file off the bus, the neon of the motel sign blinding my sleepy eyes. And as the wheels of my suitcase stop and the key turns in the door of my room for the night, I hear the record play, though I know it has surely stopped long ago. I sit at the wooden table tucked away into the corner of the darkened motel room, humble in its simplicity. I open the cover of my journal, checking for its sacred contents, afraid that the words have faded under the pressure I have placed in their significance. Seeing the typed text describing the worst day of my life and the aftermath from it, I shut out the memories and pain from flooding my eyes, closing the cover and setting it in the desk drawer.

I grab my purse and walk out into the night, sticky with humidity. Walking to the motel office I look out into the night, thinking of how the air of this place no longer feels familiar like it used to. The lights in the rooms of my fellow passengers turned off, I feel safe to walk about, embracing the entangling heat seeping through my dress. I walk into the office, stuffy with the smell of old coffee and cigarettes, and step up to the counter. The boy behind the counter, the son of the woman who owns the establishment, looks up from his worn copy of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. So entranced with the book he does not notice me standing there. I clear my throat, trying to gently awake him from his dystopian land. He jumps, tossing the book under his chair, afraid of who might see him reading it.

“Hello, ma’am! How can I help you?” His voice shakes a little. He is young, though older than I remember him. I make a shaky smile, afraid he might remember me.

“Would you have any large envelopes by chance?”

“Oh, yes! Though, if you plan on sending something tonight it won’t go out in the mail until tomorrow afternoon.” As he talks, he shuffles through the desk drawer, in search of the manilla envelopes. I nod and let him know there is no trouble with that. I stand there waiting, looking around the power blue office, watching my tired reflection in the glass windows looking out onto the empty street. The greyhound glimmers in the neon of the motel sign. It looks so tempting, and I imagine myself boarding, running away from my problems, again. As I begin to seriously consider it, he finds the envelope.

“Would you like a stamp with that?” I shake my head and he hands me the envelope, feeling frail in my worry-worn hands.

“Thank you. How much is it?” I begin to jostle my purse for some loose change. He tells me the amount and while I wrestle out coins of silver and copper, the boy grabs the receipt book. He asks for my name as I load the coins onto the counter. I stop and look up at him. His earnest eyes have no malicious intentions, but I cannot help but feel defensive. In a whisper almost too low for my own ears, I tell him.

“Beth Grayson.” Before I can set the last coin on the counter I feel the air in the room change. I look up, reluctant to do so. The sweat rolling down his temples seemed more prominent, though the water hanging in the air between us had not changed its density. It is his turn to form a shaky smile. He looks away from me in the same fashion he had tossed his book, afraid of me noticing his widened eyes.

“Thank you, Ms. Grayson, here’s your receipt.” He places the trembling receipt on the counter between us, the demilitarized zone. No one wants to touch a missing girl’s sister. I leave the office, knowing that I have started the whispers that will soon echo through town by even entering the place. The rest of town would soon know. Again, the key turns in the door of my room, though this time, I have come back dripping sweat. I hold the promise I made to her in my hands, the flimsy manilla paper. I collect my journal from the desk drawer and grab the letter tucked between its crisp pages, the one I wrote months ago. I settle both into the envelope and mark the front. Detective Eugene Matthews. Quincy Police Department. I seal my plea into the folds of the envelope and place it back into the desk drawer.

Settling into my covers, I imagine her walking into my empty bedroom to hear the voice as I hear it now. I see her gingerly slipping the record into its lovingly-worn cover leaning against my nightstand lamp, placing it in the nightstand as Dad used to have it. Did she hear it when she walked in? Or had there been a dip in the music, a break between songs? Maybe she began to settle into her usual afternoon spot when the swell of a familiar voice grasped her ear. I imagine her setting down her colored pencils, the ones Mom and Dad got her for Christmas, an artifact of another time we would never spend together. I see her slowly walk to the door covered in photographs of our weekends in the mountains, walking amongst the cattails in the swampy parts of the forest, and eating at John’s Diner, devouring their famed biscuits.

Though I imagine the record in that nightstand table as I pull these unfamiliar covers tighter around me, tucked away in the labyrinth of our days together, I still hear it playing.

I hear it with such clarity, every note, every syllable, that I cannot help but believe that maybe she is in my empty apartment bedroom twirling with the song, feeling my hands in hers as much as I feel hers in mine.

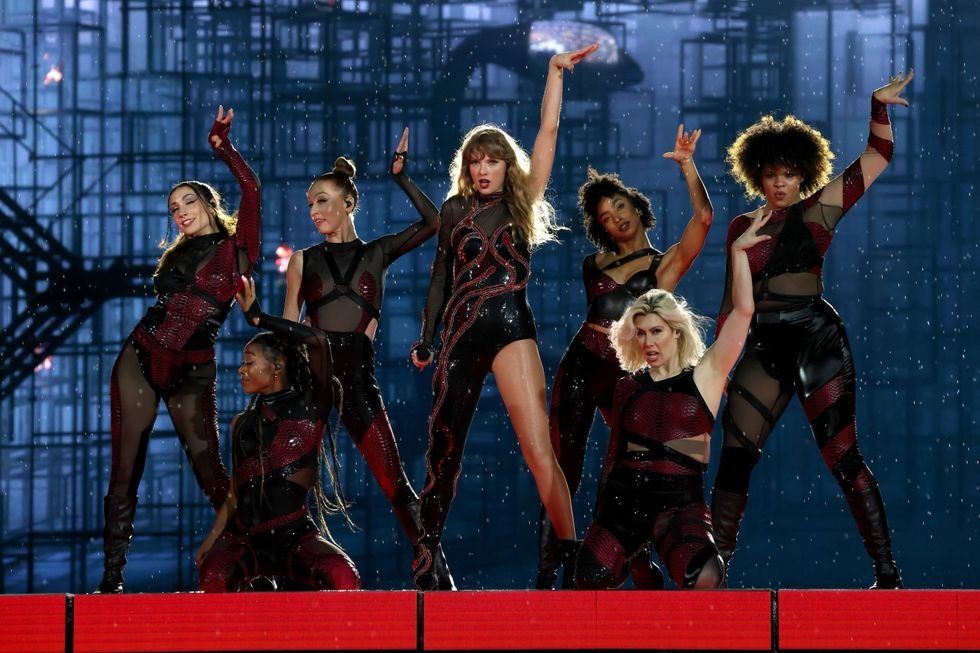

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.