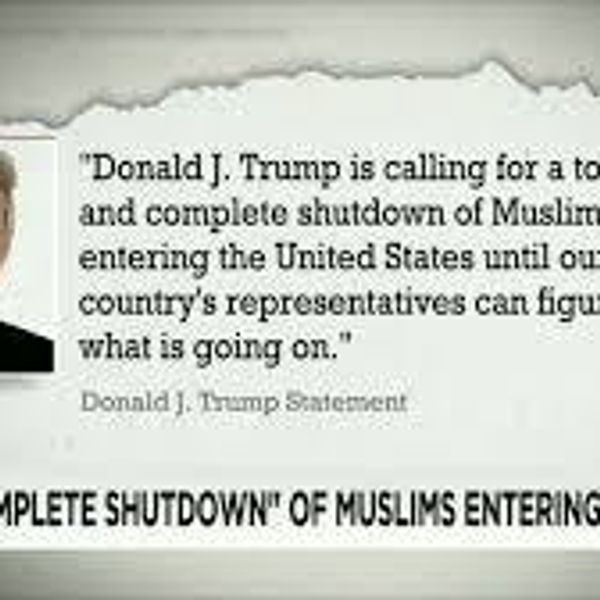

I am accustomed to the inevitable backlash and gaslighting that accompanies being an outspoken survivor, apt to ignore those who prefer my silence, but I was not prepared for the response when I shared with family and friends I was a phone sex worker. Though I received a lot of support, I was also met with hostility and disgust. A vitriolic exchange between my aunt and I was especially triggering; she claimed my sexual abuse could not be “real” if I was a sex worker. This dismissive sentiment was repeated nationally a few weeks ago when Donald Trump responded to porn star Jessica Drake’s claims of sexual misconduct by saying “I’m sure she’s never been grabbed before.” His supporters chimed in all over social media and echoed his poor understanding of consent, invalidating Drake simply because of her work.

These responses are not unique or unusual. The sex industry has always been treated as a shameful, forbidden subject, despite the number of people who view pornography (70 percent of men and 30 percent of women) or participate in some aspect of the industry such as “camgirl” sites, strip clubs, or phone sex services. This aura of secrecy around sex work not only leads to ignorance, but is extremely dangerous for the women and men who work in the industry.

How do we differentiate between a sex worker’s career and consent if we are not taught? How can we stop dehumanizing sex workers if we refuse to acknowledge them in the first place? How do we end the stigma that has existed around the sex industry for so long?

Regulation, reform, and education.

Vocativ recently published an article about the French organization Le Mouvement du Nid, and their online campaign that advertised fake, murdered escorts to raise awareness around sex work and sexual violence. However, the campaign was not produced in efforts to make the industry safer, but was simply propaganda to abrogate sex work entirely. Here is the truth: abolition never works. Less than 100 years ago, The United States endured the Prohibition era which incited an increase of organized crime; this is typical for any unregulated or illicit services or goods.

Studies have already shown sex workers are at much greater risk of experiencing sexual violence or sex trafficking in areas where prostitution is criminalized. To boot, in countries where sex work is legal, women become more likely to report sex crimes to law enforcement. A lack of regulation leads to a lack of responsibility — it breeds a cesspool of predators who thrive in the underground world of victims who are forgotten and cast off because of their profession.

Even regulated, and thus safer portions of the sex industry, such as porn and phone sex, must undergo reform. There is no denying mainstream pornographic media is made primarily for men; I intentionally market my phone sex line with the male gaze and fantasy at the forefront. And guess what? Fantasy, albeit occasionally disturbing or strange, is PERFECTLY OKAY. The problem arises when fantasy and acting are mistaken for permission (looking at you, Mr. Trump). As a sex worker, I am often told I am not allowed to have boundaries; I am told I do not deserve respect. Using sex work to invalidate and blame a sex worker for any violence perpetrated against them is the root of rape culture.

Sex workers carry a disproportionate amount of shame; we are the punchline of a misogynist’s “daddy issues” joke, the enemy of anti-sex work organizations, the heretic of religious communities, the often divisive fringe of the women’s rights movement. We are demonized by so many different groups, yet our work is voraciously consumed.

Even while porn is undisputedly woven into the daily lives of many Americans, sex workers have been legally targeted in recent months. Sex work activists in California are currently working against Prop 60, a bill that not only attacks their body autonomy, but also could allow easy access to the performer's personal information. Sex workers protect themselves from violence through anonymity and the use of aliases; to expose these women and men, in my opinion, is a breach of privacy that is worse than exposing your internet history.

Additionally, in late April, Governor Gary R. Herbert of Utah declared porn a public health hazard. The declaration states porn treats “women as objects and commodities for the viewer’s use” and was written as an attempt to educate the youth in Utah about the harm of pornography. First of all, this declaration is divisive; it separates men from women and reinforces the incorrect assumption that women cannot enjoy porn or sex. Also, instead of a decree attacking the sex industry and the people who make their livelihood from it, we should seek to first change our misogynistic culture. Popular porn that focuses on the degradation and objectification of women is just a cinematic reflection of how we view women in reality. Governor Herbert's resolution reads like a satire. In a state that has higher rates of sexual violence than the U.S. average, rates of unintended pregnancy around 23-30 percent, and abstinence-only education, Utah’s state government has much bigger health issues to address than porn.

The perception of sex work will only begin to change when more sex positive education is taught in schools, and in the home through open conversation. Sex is natural, masturbation is normal, and exploring sexuality is crucial to development; however, that is not the narrative in American high schools. The curriculum taught is only a small fragment of sex education; most states do not require teachings about birth control methods, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), or rape. Abstinence-based education is used in 26 states, despite the proven increase of STIs and teenage pregnancies with abstinence teaching methods. Sex education molds how sex workers are perceived and treated — when adolescents are taught being sexually active makes them less of a person than their peers, why wouldn’t they see us as the faces of self-degradation? Our images and voices equated to the words worthless, shameless and felonious, instead of consensual, confident and employed.

I know talking about sexual violence and the sex industry is uncomfortable. It is a conversation that forces each and every one of us to examine our own prejudices and ingrained sexism that make us more willing to accept a woman as a product rather than a living, dynamic creature — one who is allowed to possess both her sexuality and pain.

This isn’t a wild, distant notion: To maybe just see a sex worker as a person?

Read more statistics about sex work and violence here.