During a day out at the mall with my little sister, I noticed myself surrounded by floor-to-ceiling clothing, lingerie and perfume ads. They could have been advertising the same product for all I knew, as each ad was dominated by a thin, white, partially nude model. Later that week, while sharing New Year's resolutions with my friends, I noticed nearly every single one of them included a goal about dieting or losing weight. That evening, while scrolling through Instagram, I "liked" selfie after selfie of my friends in their new clothes or on vacation, all of the pictures taken from strategic angles in optimal lighting. For my entire life, I've observed the obsession with appearance that saturates our society, and I began to wonder whether this obsession comes from ads in the mall, or if advertisers are simply taking advantage of the natural vanity and insecurity we feel towards our bodies.

The self-documentation of our lives on social media, especially after the rise of the selfie, blurs the lines between advertisement and self-portrait. Millennials have been mocked for the invention of the selfie, being nicknamed "Generation Me." Supposedly, taking pictures of ourselves and showing them off to our friends is egotistical. When taking my own pictures, especially after walking through the mall as a young woman — many clothing stores' prime consumer base — I often ask who I'm taking this picture for and what inspired me to take the picture in the first place. Personally, I am torn between loving the selfie as a message to spread self-love or despising it as a perpetuator of peer pressure and negative body image.

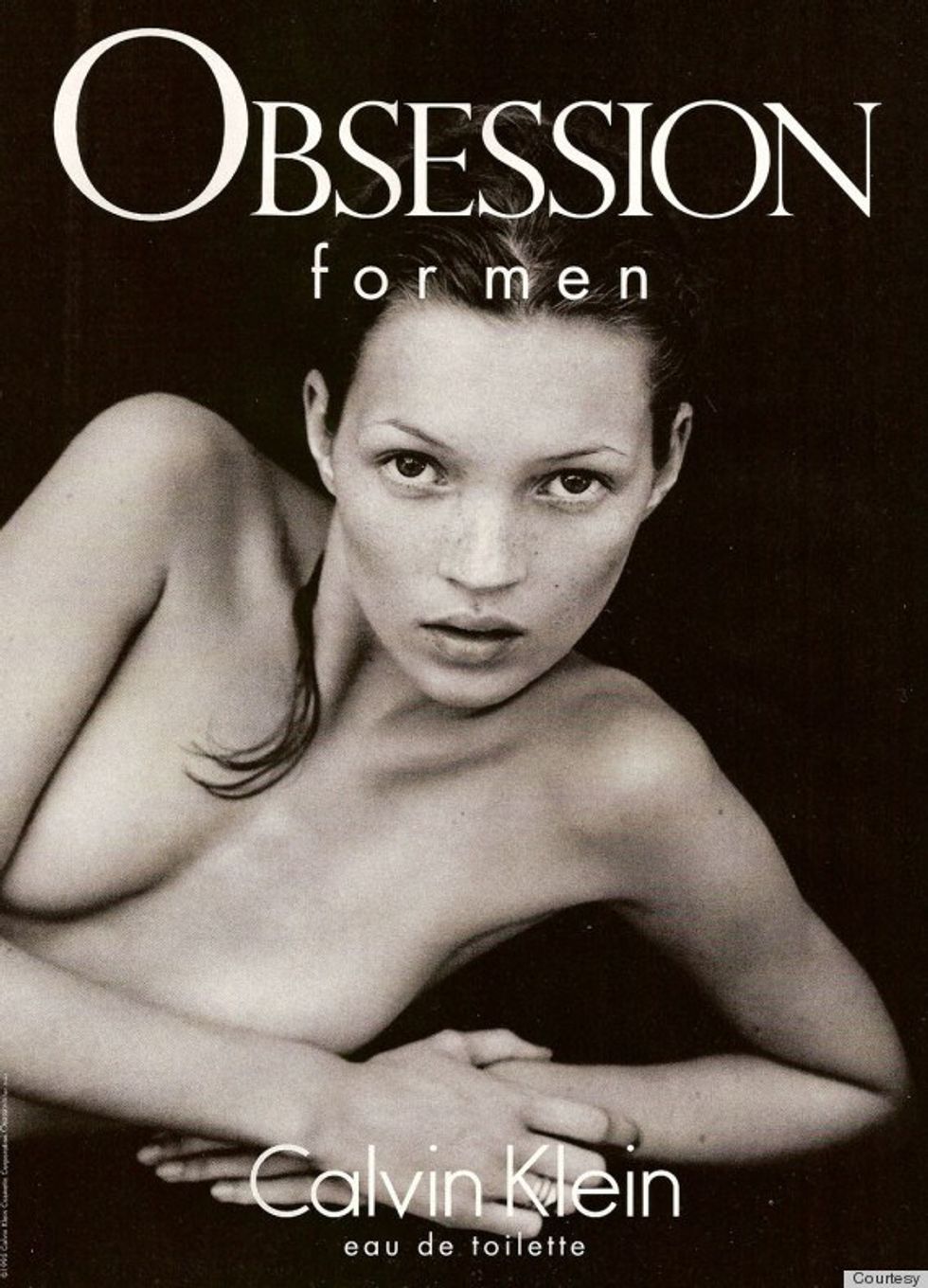

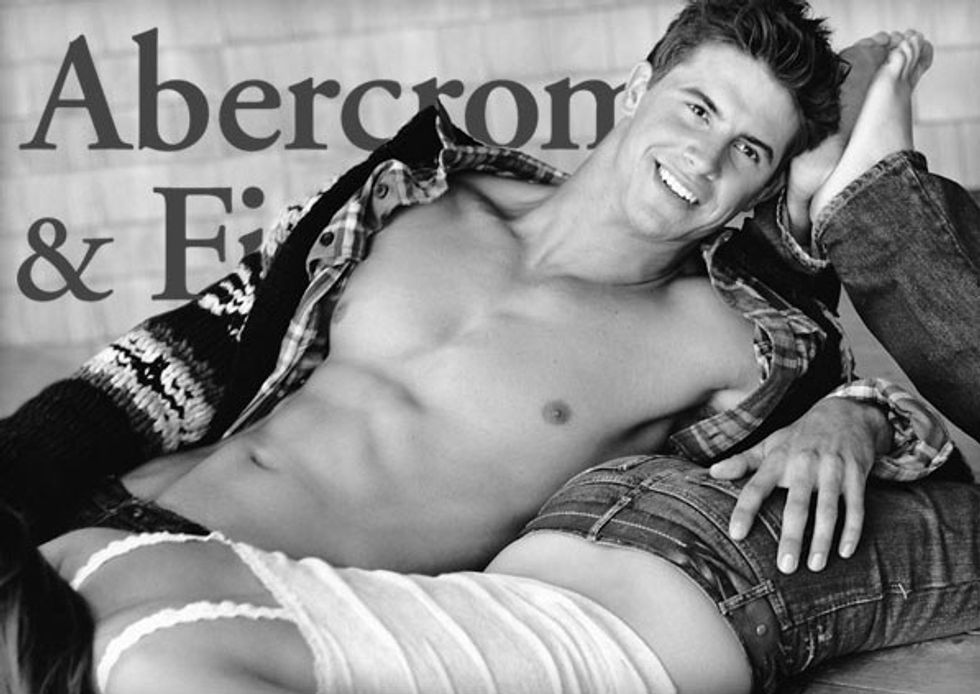

These advertisements, from Calvin Klein and Abercrombie & Fitch respectively, depict idealized versions of the subjects. They are all thin, without marks or blemishes on their skin and the high angles and lighting create shadows that make their muscle and bone structures as prominent as possible. All three models are also blatantly objectified. The Calvin Klein ad is “for men,” complete with a topless woman taking up the entire space. The man in the Abercrombie & Fitch ad has his hand on the young woman, whose face isn’t even being shown, and his body is also overly sexualized by the open shirt. The ads are used to sell a product, but they also sell a certain body image and messages of sexual objectification to the consumer.

In a similar way, selfies posted on social media "sell" the subject. The other users of a website are the consumers, and the owners of the images are showcasing their most flattering features and appealing aspects of their lives. They also take after the advertisements shown above. The angle of a selfie is typically from above, making the jawline appear more angular and the face narrower; bright lighting (or photo editing post-snapshot) minimize any visible blemishes; the photographer is also usually doing something noteworthy that will evoke envy from social media followers.

The difference between the glorification of the subject in advertisements and in selfies is that advertisements take the agency away from the subject. In a selfie, the degree to which the subject flatters their own image, the amount of skin that is shown, or the audience that sees the image is entirely in the photographer’s own hands. Selfies are, therefore, self-portraits: they are a form of self-expression, portraying the artist’s relationship with their own image.

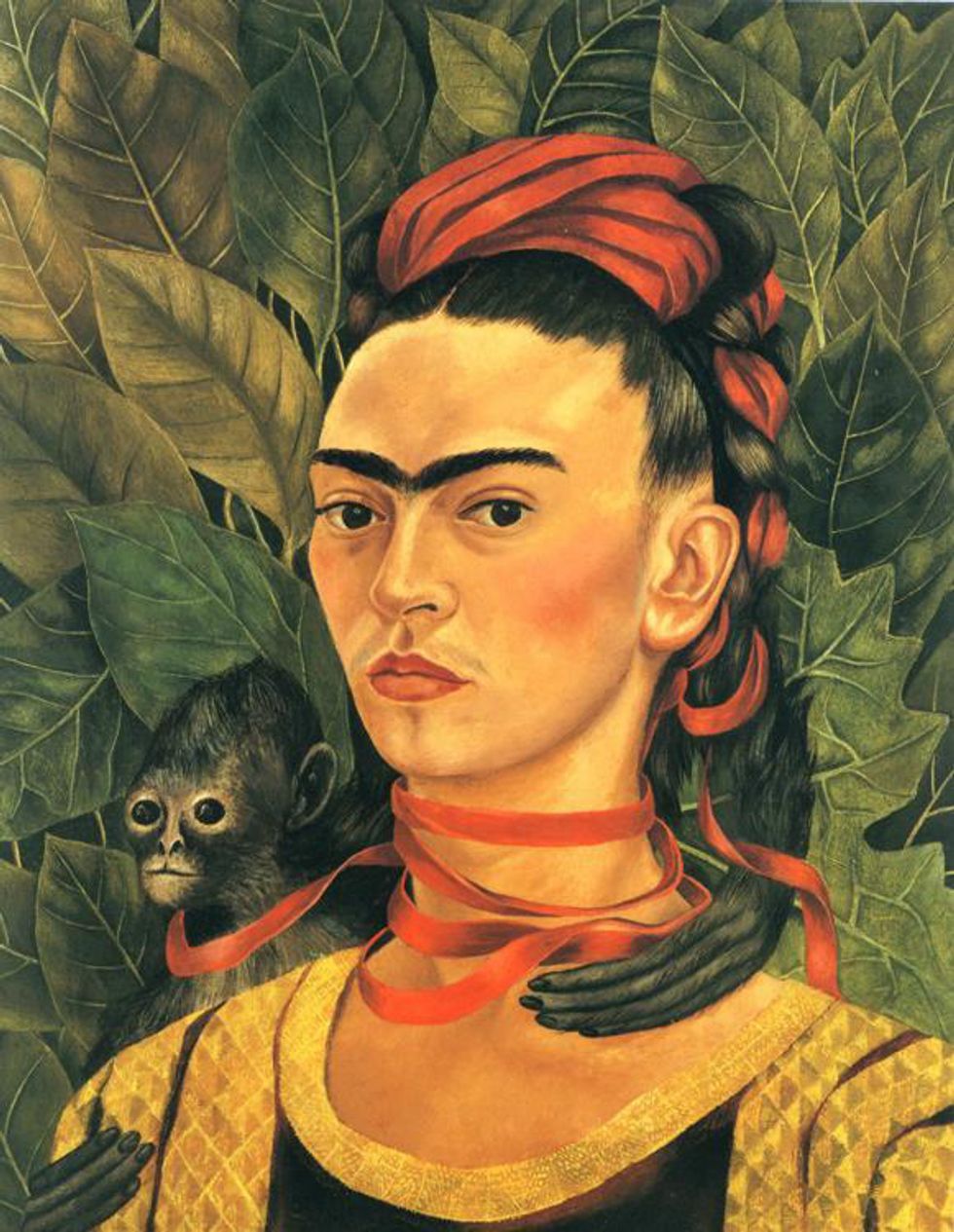

Rembrandt’s “Self-Portrait at the Age of 34” circa 1640 and Frida Kahlo’s “Self-Portrait with Monkey” of 1940, while 300 years apart, both feature elements of selfies today. They are taken from a slightly elevated angle, wearing clothes that make them look sharp, gazing confidently at the viewer (which, if taken as a photograph, would be the camera lens).

Even having portraits taken to our liking is a recurring theme throughout history. In “Louis XIV (1638-1715)” by Hyacinthe Rigaud, circa 1701, the historical king of France poses in his finest clothing, surrounded by luxury. He wears red high heels and is quite obviously showing off his legs in an unnatural pose which accentuates well-defined thigh and calf muscles. He is essentially doing exactly what every selfie-taker does when they tilt their chins, puff up their chests and pucker their lips in a fish gape for the camera.

The key difference between the selfie and the classical self-portrait is the better accessibility. Many people have a front-facing phone camera, and it does not require much artistic skill or time commitment to take a snapshot, enabling an entire generation to learn a new technique of self-portraiture.

As for my personal stance on taking selfies, I feel comfortable using them as a medium of self-expression. However, I won't look to ads to base my inspiration, but rather to artists like Frida Kahlo, who in her self-portraits emphasized her own "imperfections," such as her famous unibrow, and celebrated how this made her unique. I believe self-portraits can become a movement to reclaim individuality and teach self-acceptance.