"Anyone have anything on the table they want me to throw out?"

"Yeah, throw me away while you're at it I am literally trash--"

"That's one for the jar," my friend says as she gathers up the trash and throws it out.

Another one for the jar? I think, I really didn't realize how often I do this.

The year is 2018 and I am a junior in high school. At this point, it must be the fourth time I put "one in the jar" all day.

Of course, the jar was in no danger of filling up-- it wasn't a real physical object, but a concept. The jar represented every self-deprecating or negative joke any of my friends or I had made, for the purpose of making us aware of the frequency of our usage of humor as a coping mechanism.

As Generation Z kids (defined as born between the late-90s to the mid-to-late 2000s), self-deprecation was not unfamiliar to us. In fact, around this time, it was totally normal for someone in our grade to say "I just want to die," out of the blue, and for the standard reaction to be "me too," or "same." But while humor can be used as a way to cope and make peace with one's feelings, it is also important to acknowledge how it contributes to the normalization of negative language in relation to the self.

Clearly, the circumstances Gen Z face shape their mental health. According to the Economist, across all boards (regardless of gender, race, or class background) 70% of Generation Z believes depression/anxiety is a major issue among their peers, and Gen Z is the most depressed generation. Gen Z is also the most ethnically diverse age group in America, with 48% of the iGeneration being nonwhite-- and while the depression rate for teens/young adults of color is lower than their white counterparts, studies have shown that "[e]thnic/racial minorities often bear a disproportionately high burden of disability resulting from mental disorders."

Growing up in post-9/11 America and living through one major recession (soon to be two), it may be unrealistic to expect Gen Z to be as optimistic as their older siblings, parents, or grandparents. The social unrest witnessed by Gen Z, including police brutality, gun laws/regular school shootings, increasing wage inequality/class disparity, the deportation crisis, the complete lack of support for student debt, and the sense of impending doom caused by climate change have all contributed to the degradation of Generation Z's mental health.

Additionally, growing up with social media as a major part of their adolescence or childhoods has affected Generation Z greatly. The social pressures caused by the vast majority of their peers regularly using social media results in fomo, also known as the "fear of missing out," as well as increased rates of cyberbullying, a rise in loneliness, and more parasocial relationships.

Gen Z is often compared to the Silent Generation, who grew up post-World War II, but they also share a similarity with the Lost Generation, who grew up post-World War I. Like the Lost Generation, who birthed the Dada movement, Gen Z copes with the poor social/economic conditions they inherited by embracing absurdity and existentialism.

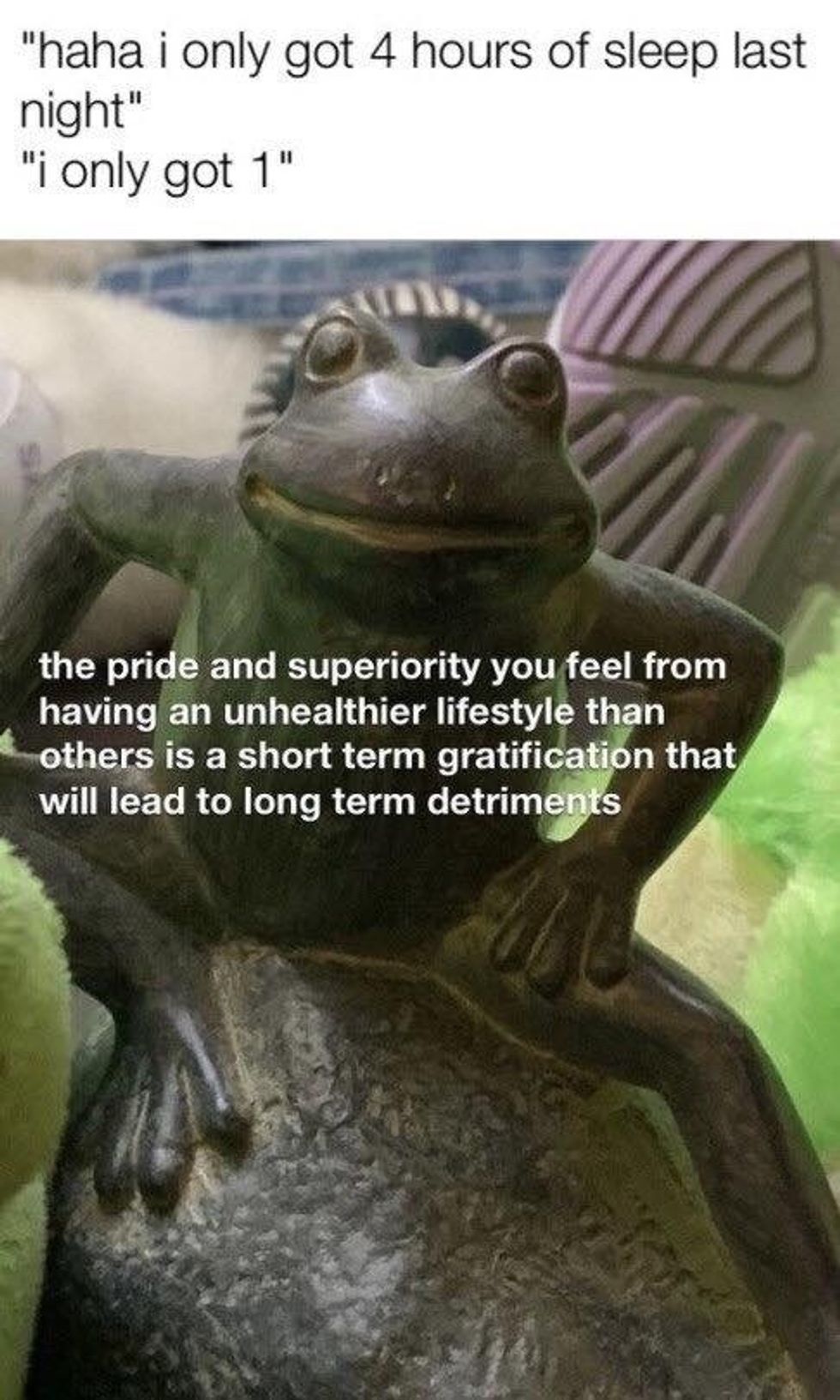

The role of Millenials in shaping the Internet has contributed to the development of Gen Z's particular sense of humor. Teens and young adults have observed Millenials' similar coping mechanisms on social media. As avid users of social media, most memes are targeted towards Gen Z, and the vast majority of memes are existential, absurd, or self-deprecating. In other words, because Neo-Dadaist humor was popularized on the Internet, it played a significant role in shaping the self-image of Gen Z-ers. I mean, we were the ones that unironically participated in the Tide Pod challenge for a laugh, not really caring if our stomachs had to be pumped. Who cares if I'm in the hospital when climate change will kill us in a few years anyway?

On one hand, we are opening up conversations about negative self-image, normalizing being neuroatypical. Yet, we should really consider the not-so-positive effects of habitually putting ourselves down. Sure, insecurity is relatable, and there is no point in pretending that everybody is confident all the time.

But to what extent do throwaway comments about how much I hate myself and that you do too actually help either of us? Yes, we may feel less alone, which is always a good thing, but are we taking steps to improve ourselves? What does conversation do if it is not analytical, if it does not serve to help find a solution? On the outside, we may be normalizing conversations about mental health, but on the inside, we are normalizing talking ourselves down. Others around us internalize that we are human and not perfect, but we begin to internalize that we do not deserve better and that that is a normal way to feel.

I often reflect on the reasons why junior-year-me created "the jar" in the first place. The reality is that it is not normal for an entire grade of minors to hate themselves. We were children who were terrified of how vulnerable we were to the systems around us, and our instinct was to seek comfort in each other, unofficially asking, "so, it's not just me, right?" In the end, it had gotten to the point where I thought that this way of thinking was normal, when none of it was. All of us needed help or relief. I knew that as a minor, there was realistically very little I could do to help myself, let alone all of us. At the same time, I felt complicit in ignoring warning signs-- my own, and those of my peers. The best solution was to stop doing it, to get my friends to stop doing it, and to have a real, productive conversation about steps we could take to help ourselves.