Sparked by an increased interest in content and process over form and finished product, the Surrealist movement became one of the most popular forms of artistic expression during the early 20th century (Raimondo, 8). Defined as, “Recourse to the imaginary, to dreams, to the unconscious and to chance,” Surrealism is essentially the expression of deeply imaginative, borderline spiritual, self-reflection, using symbology, psychoanalysis, and automatism, amongst many other methods, to break the barrier between the subconscious and the conscious (Waldberg, 7). The movement began in Paris, branching off from the DaDa movement, with higher goals of, “Accessing the subconscious,” (Caws, 30). Spearheaded by painter Andre Breton, Surrealism interested artists from all over the world who felt that no other artistic movement gave them the, “Poetic license, in terms of painting,” that Surrealism offered (Waldberg, 8). In 1929, after a small fall out amongst several members of the Surrealist movement, Breton began searching for new, young painters to join the group’s quest for philosophical, spiritual, imaginative, and, above all, artistic revolution (Ades, 4). Around the same time, a young painter named Salvador Dali was beginning to find his own ideas aligning with those of the Surrealist movement (Ades, 4). Born in a small fishing town in Spain in 1904 (Ades, 3), Dali’s unique and psychologically challenging pieces are inspired by events such as those from his childhood, his readings of Sigmund Freud, and his never-ending obsession with intellectual advancement (Descharnes/Neret, 72-74). In 1928, Dali partnered with a friend, Luis Bunuel, to create a Surrealist silent film titled, “Un Chien Andalou,” which caught the attention of Breton and his colleagues (Ades, 4). In 1929, Dali officially subscribed to the Surrealist movement at the request of Breton, and began creating and displaying work much more frequently amidst the artistic community (Descharnes/Neret, 26).

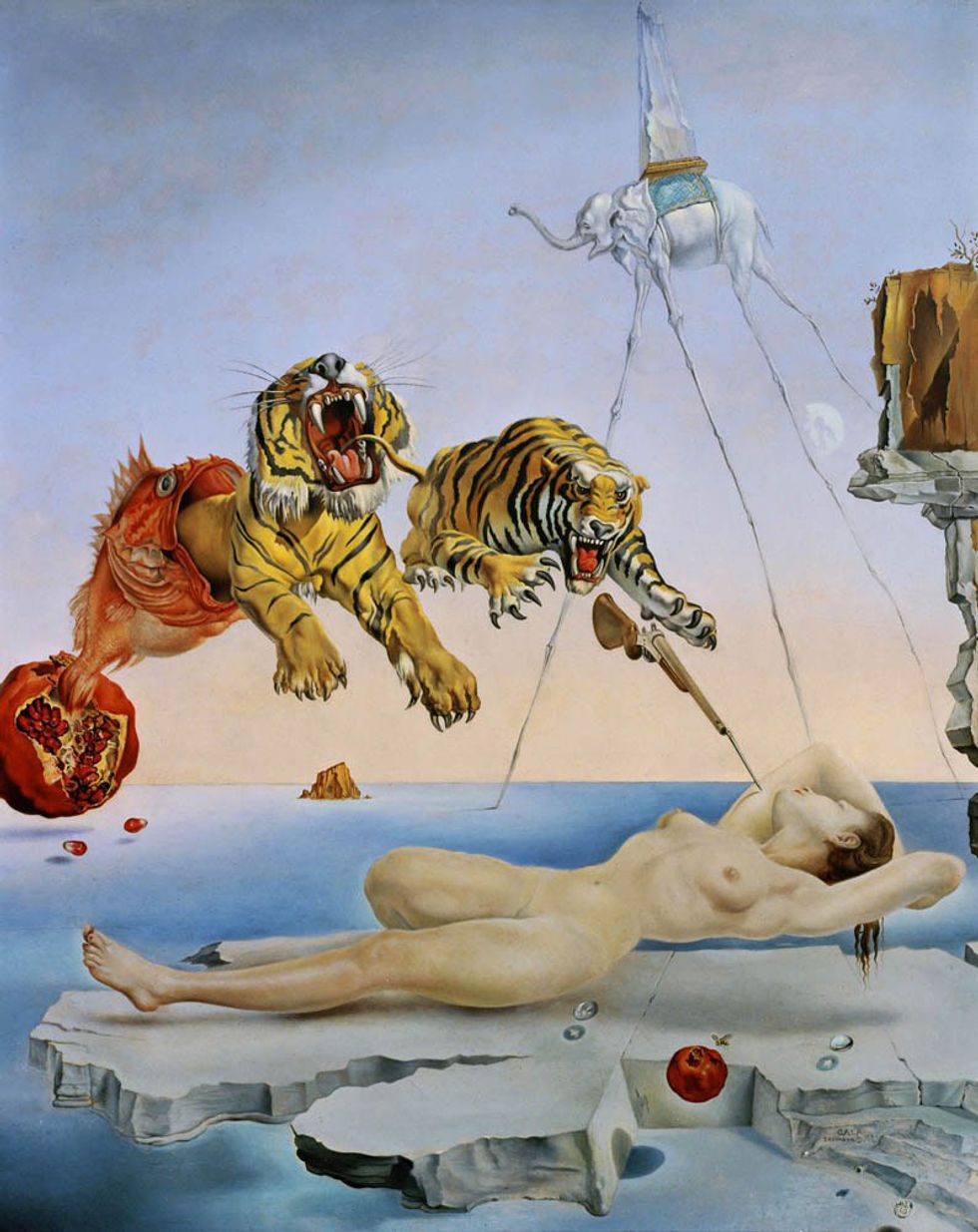

Fig. 1. Salvador Dali, Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening, 1944, Oil on wood, 20” x 16”. Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid.

After fifteen years of painting in the Surrealist tradition, studying psychoanalysis applied to subconscious thinking and dreams, and developing his own personal lexicon of symbolic language and philosophies, Salvador Dali, one year before officially parting with the Surrealist movement in 1944, created a symbol heavy painting titled, Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening (See Fig. 1) (Descharnes/Neret, 78). The strong sexual undertones, common in most Dali paintings, are especially prominent in this piece. The composition centers around a naked Gala (Dali’s lifelong companion) who is floating just off the ground, and uses elements from the Freudian sexualanxiety theory to illustrate the artist’s internal sexual conflicts (Ades, 14). This piece, the culmination of a lifetime of imaginative painting, captures very clearly the goals and themes of both Dali, and the Surrealist movement as a whole. Essentially, Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening by Salvador Dali, explores the interactions, similarities, differences and legitimacy of dreams and reality, as well as the universal anxieties and struggles with one’s own sexuality.

Salvador Dali grew up in a small fishing town in Figueres, Spain (Biography). His full name, Salvador Felipo Jacinto Dali y Domenech, is actually the same name that his brother had, though he died before Dali’s birth (Biography). Because of this, or perhaps in addition to it, Dali grew up being told by his mother that he was a miracle; the reincarnation of his older brother (Biography). This probably only added to the sense of individualism and eccentricity that Dali would come to embrace later in life. He was encouraged by his mother to paint and express himself in any way that he wanted to, which helped kick start the career of the young painter (Biography).

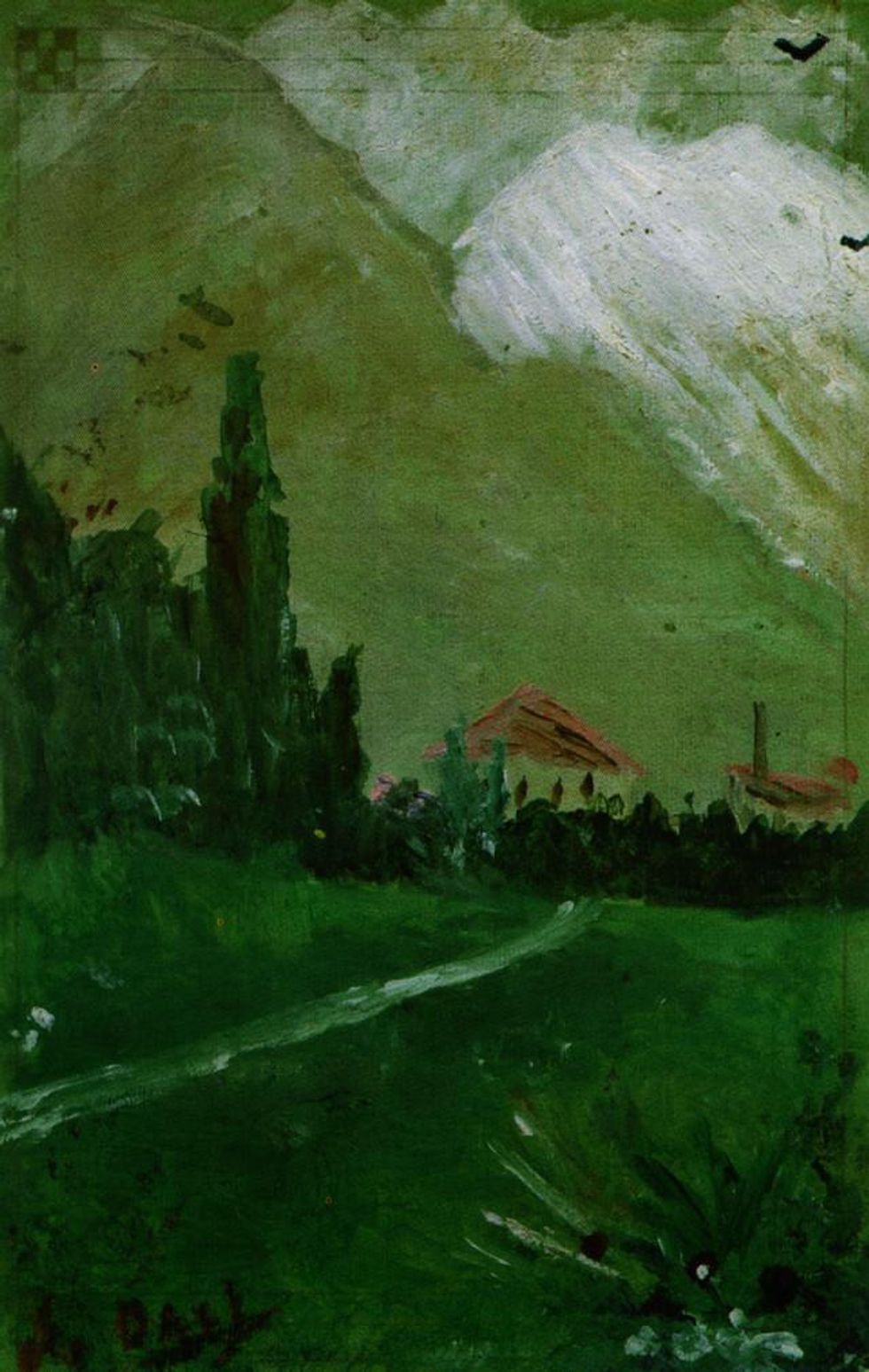

Fig. 2. Salvador Dali, Landscape Near Figueras, 1910 (Painted at 6 years old!), Oil on Postcard, 14cm x 9cm. Private collection of Albert Field in Astoria, Queens.

From age six or earlier, he set to work on paintings almost every day; paintings of his family home amidst the cliffs of Figueres, social events, very expressionistic landscapes, as well as still lives (See Fig. 2) (Biography).

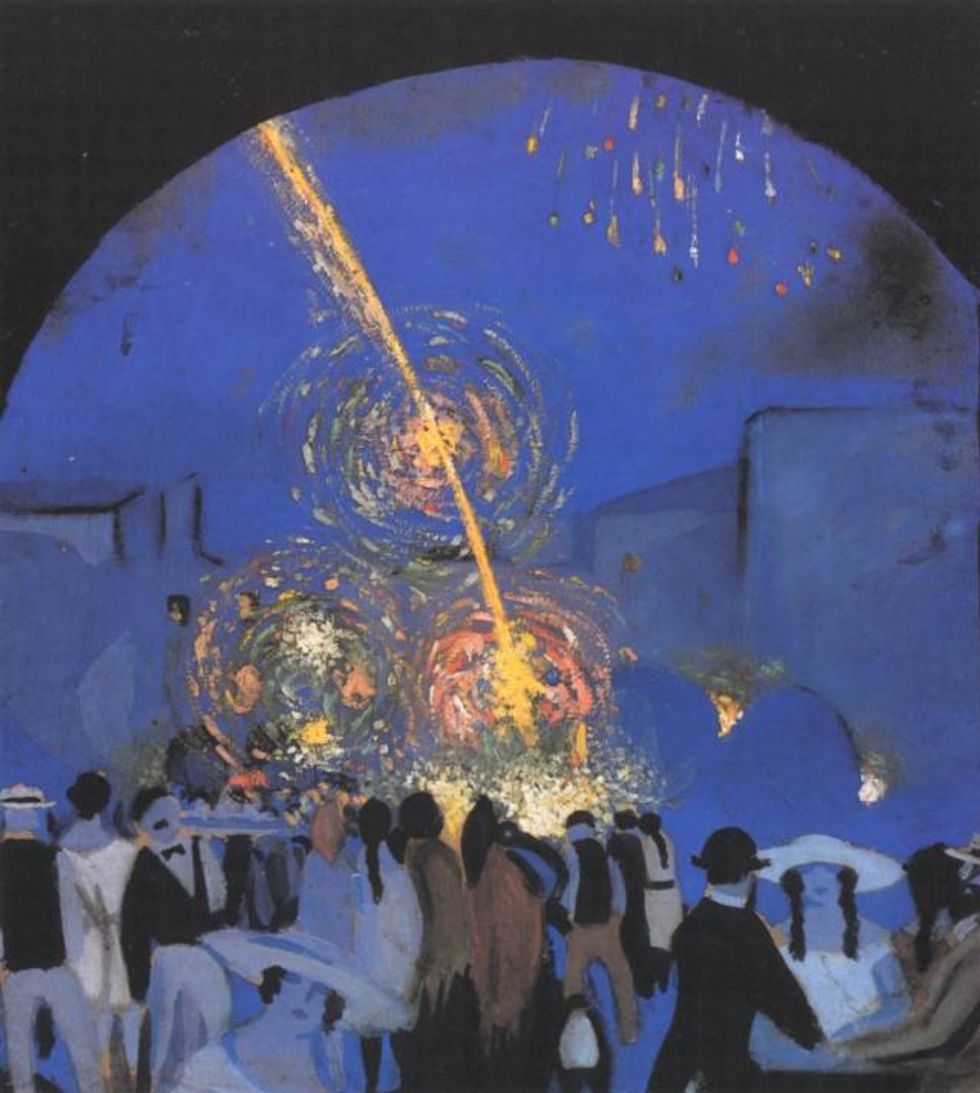

Fig. 3. Salvador Dali, Fiesta in Figueras, 1914-16, Gouache on Canvas. Size unknown, Location unknown.

The earliest signs of the style that he would later hone over the years, came in his painting of the Fiesta at Figueres, 1910 (See Fig. 3.) (Biography). This is the earliest example of his symbolic style, whether intentional or not; the faceless figures, the dark backdrop of night contrasting against the bursting illumination of streetlights, or perhaps fireworks, all seem like elements of a “normal” Dali painting. What is more amazing, is that these two paintings were made before Dali had turned ten, and helps explain why his parents helped him in any way they could to follow his painting instincts. Dali went on to attend the School of Fine Arts in Madrid, living there as well. Art school was where he met the future collaborator of his two Surrealist films, Luis Bunuel (Ades, 4). This relationship, along with frequent trips to Paris to meet famous artists of the time, would inspire Dali to begin creating art in the Surrealist tradition (Ades, 4). After two years of school, Dali was suspended for a full year for organizing a riot against the staff of the college because of their “incompetence” (Ades, 4). After the one year suspension, Dali told off his student review panel, saying that no one in the school was competent enough to evaluate him; this earned him permanent expulsion (Biography). School simply was not the place for Dali; he found much more success traveling and studying with other artists in the field, studying the famous pieces of the Renaissance, and painting as often as possible (Ades, 26). This sort of self-teaching was clearly just what Dali needed to complete his growth as an artist, because during the late 1920s and early 1930s, he started to earn more and more popularity, and became a big name in the Surrealist tradition (Ades, 4). Along with his growing success, he met and married the woman who became his everything, Gala. Gala was the right brain to Dali’s left brain; while he spent time in his own thoughts, painting, too busy to be distracted by finances or contracts, Gala helped support him by being his organizer; without Gala he would not have made it as a successful artist (Biography). Throughout his life, the constants for Dali became Gala, his own eccentricity, and the amount of paintings he was producing. From 1910 to 1989, Dali produced thousands and thousands of paintings, each of which had the same, fundamental, psychological basis in mind. Dali and Gala lived comfortably from the money that wealthy patrons, such as Edward James, paid for the paintings, and the two were in love until the day Gala died. So devastated was Dali at the loss of Gala, that his heart began to give up, until it finally stopped for good in Figueres, Spain, his place of birth, in 1989 (Biography).

Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate was painted by Salvador Dali in 1944 using oil on wood, and measures about 20” x 16” (See Fig. 1.). The setting of the scene is a smooth pastel landscape, with a horizon line placed at the bottom third of the composition. There is a set of rocky cliffs on the right hand side of the painting, and, combined with the pastel colors, creates a very smooth, soft, flowing feel to the painting, and accents the rough texture of the cliffs. The main subjects start at the bottom with a small patch of elevated rock, over which floats Dali’s life companion and muse, Gala. Gala levitates, outstretched and nude, just off the ground, and her face is turned away from the viewer. Below her, a very small bee flies around what can be presumed to be, due to the larger version in the background as well as the title, either a floating pomegranate or pomegranate seed, to either side of which floats a water droplet. Moving back into the painting, we see a much larger pomegranate, from which bursts a large fish. Both the pomegranate and the fish are painted in a bright reddish orange, and stand out as the two most saturated elements of the painting. Out of the fish’s open mouth, escapes a large tiger, with its mouth open wide. Out of that tiger’s open mouth, comes yet another tiger, only this tiger appears to be looking and lunging towards Gala. The three animals exploding from the pomegranate create a pleasing compositional arc that draws the viewer’s eyes right to the final element in the foreground; a gun with a bayonet attached. The weapon is so close to Gala’s skin that it casts a shadow that is almost indistinguishable from end of the bayonet, suggesting that it is very close to her body. Finally, in the background, there is one more figure; a tall elephant carrying a large crystal. The elephant has legs several times longer than its body, which also appear very thin in comparison to the scale of the elephant. On top of its back, the elephant also carries a large crystal that is pointed, large and thick.

The pastel colors of this painting were chosen by Dali, as in many of his other pieces, to be taken as a meaningful, artistic decision. The light, flowing blend of blues, pinks, oranges, and yellows all come together to link the viewer to the Surrealist themes of the painting, while the horizon creates the illusion of a very long, seemingly never ending ground that recedes into infinity. The soft, light, springtime colors of the painting allow the viewer to feel, if only subconsciously, a sense of the sexuality and nature that is prevalent in this piece. The landscape’s rocky cliffs are a way for the artist to express his appreciation of his childhood memories; he often mentioned how fond he was of the days he spent in the small, rocky, cliff filled Spanish village he was born and raised in (Ades, 4). This sort of rocky background is very common in a lot of Dali’s paintings, as was the idea of preserving and building on one’s own childhood experiences. The light blue, that acts perhaps as a long body of smooth water or simply an unreal landscape with impossibly smooth features, pushes the figure of Gala forward very softly, leading the eyes to the front of the composition, as well as signifying her as the main subject. Dali’s main subject in this painting, his life-partner Gala, floats outstretched above a rock, which floats above the blue, sea-like ground. By having Gala floating as opposed to laying down, Dali creates a very dream-like, unreal scene, though painted very convincingly, and points towards the question and debates around reality versus fantasy. The relationship between Gala and Dali fueled a lot of Dali’s work; she was his muse, his love. So, the fact that she is about to be pierced by a bayonet coming out of a tiger’s mouth, which is coming out of another tiger, which is coming out of a fish bursting from a pomegranate, is very significant. According to Freud, “In dreams, a wild beast tends to represent the anxieties in one’s life that seem either too daunting, too challenging, threatening, etc. to confront,” (Ades, 56). The bayonet and the teetering obelisk on the back of the elephant, whether thought of as phallic or dangerous, both generally represent paranoia, in this case sexual paranoia, in the mind of the dreamer/artist. This sort sexual anxiety shown through dream-like symbolism is an example of the paranoiac-critical method that Dali coined; the idea that the psychoanalysis of dreams can be applied to painting. This is a very valuable and important contribution that Dali made to Surrealist movement, and this piece in particular uses those Freudian ideas and themes to create its symbology (Alarco). Additionally, in religious iconography, pomegranates tend to represent sexuality, the sin of sex, or the decay of youth; a reference to the forbidden fruit. The idea that Dali’s anxieties are rooted in his sexuality, or the sin of sex (the pomegranate), and seem to be affecting Gala in a negative way (the beasts, the unstable obelisk, the bayonet) suggests that Dali had very big worries about the love of his life. Another interesting interaction to notice is the bee flying around the pomegranate at the bottom of the page. The viewer can look the painting over several times and not notice the small bee getting ready to sting the pomegranate seed, or the two water droplets floating nearby. This interaction is either a catalyst, a microcosm, or a prediction about what is happening to Gala. From the title, we can infer that the bee is a parallel to the bayonet, which means the pomegranate is a parallel to Gala. This is important because it suggests that nothing we are seeing is real; if the dream is caused by an interaction that is going on in reality, the fantasy is the surreal scene of Gala being attacked by animals and a bayonet. This throws the viewers perception of reality and fantasy out the window; how can we know what is a dream and what is real when the artist seems not to notice a difference? And how can we understand a painting when we do not know what Dali was worried about? However, the point of the piece, and Surrealism in general thanks to Dali, is not to be specific, but rather to suggest a direction for the viewers’ emotions to travel by remaining ambiguous. This permits the viewers to impose their own personal emotions and imaginations, and makes the piece more personal and relatable.

Today, it is still amazing how consistent Salvador Dali’s imagination was in producing these wildly varied, thematic paintings. Much of the inspiration for Dali’s pieces came from childhood, his lovely wife Gala, his readings of Sigmund Freud, his studies of Renaissance artists, the Romantic idea of the Sublime, and his view that living, dreaming, and dying, in essence, are all very similar (Waldberg, 38). The rocky landscapes from Dali’s childhood show up frequently in his paintings, as does the figure of Gala. These themes that seem incredibly significant to Dali, were placed in his paintings for that precise reason; he was trying to create very personal interpretations for himself, that represented the world he was experiencing. To the viewer, however, these large landscapes juxtaposed against delicately rendered, but still muscular figures, deliberately symbolizes the fragility of humankind amidst the awe-inspiring, sublime presence of nature. Dali’s studies of antiquity, the Renaissance, and Romanticism are prevalent in his pieces; his figures tend to have very colorful, humanistic features, a major characteristic of art in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Fig. 4. Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, Libyan Sibyl, 1510-11, Frescoe. 149”x155”. Sistine Chapel Ceiling.

In Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate, for example, Gala’s figure is nude and fairly muscular; reminiscent of Michelangelo's Libyan Sibyl from the Sistine Chapel Ceiling (See Fig. 4). The rendering of muscular, powerful females by Michelangelo, seems to have inspired the rendering of Gala, who also seems to be flexing her muscles. She is also clearly not a small, dainty female, but rather powerful and full bodied, even though that is overshadowed to an extent by the enormous cliffs in the background.

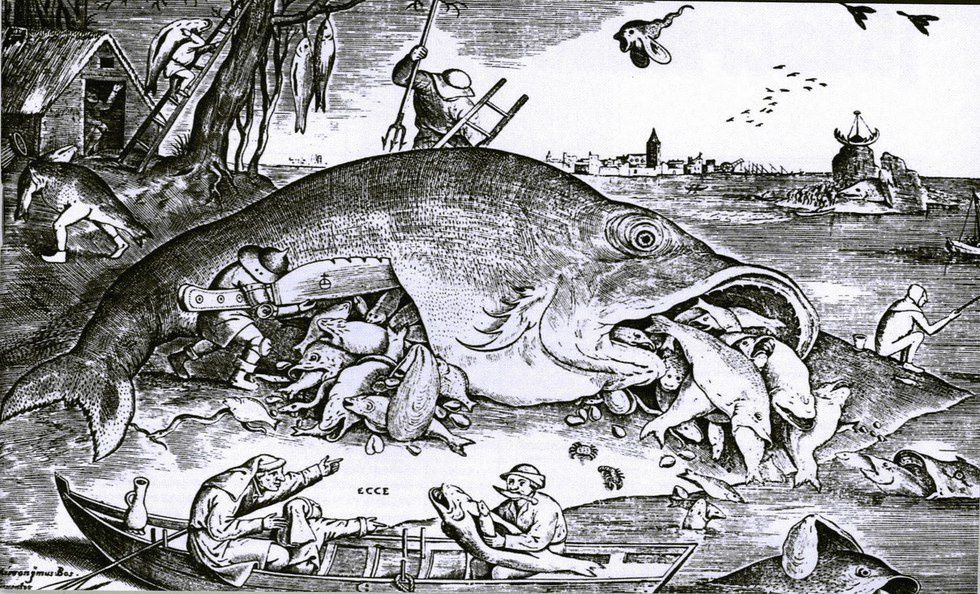

Fig. 5. Pieter Bruegel, Big Fish Eat Little Fish, c. 1557, Engraving, 9” x 11 5/8”. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

We also see beasts with other beasts in their mouths, which could perhaps be a reference to Pieter Bruegel’s Big Fish Eat Small Fish, from the Protestant Reformation (See Fig. 5). Both of these pieces show beasts with other beasts inside of them; perhaps Dali wished to show off his knowledge of classic art, or reference the idea of the working class being taken advantage of by the bourgeoisie, or a number of other meanings. Either way, the fact that there is a fish with other, smaller animals inside it, seems to be a reference to Bruegel’s work. The idea of the Sublime from the age of Romanticism is also present, something Dali probably researched during his personal studies. The Sublime is defined as the experiences surrounding infinity, the unknown, darkness, etc; anything that evokes the incredible feelings of being overpowered and awe-struck by something inconceivably bigger than you.

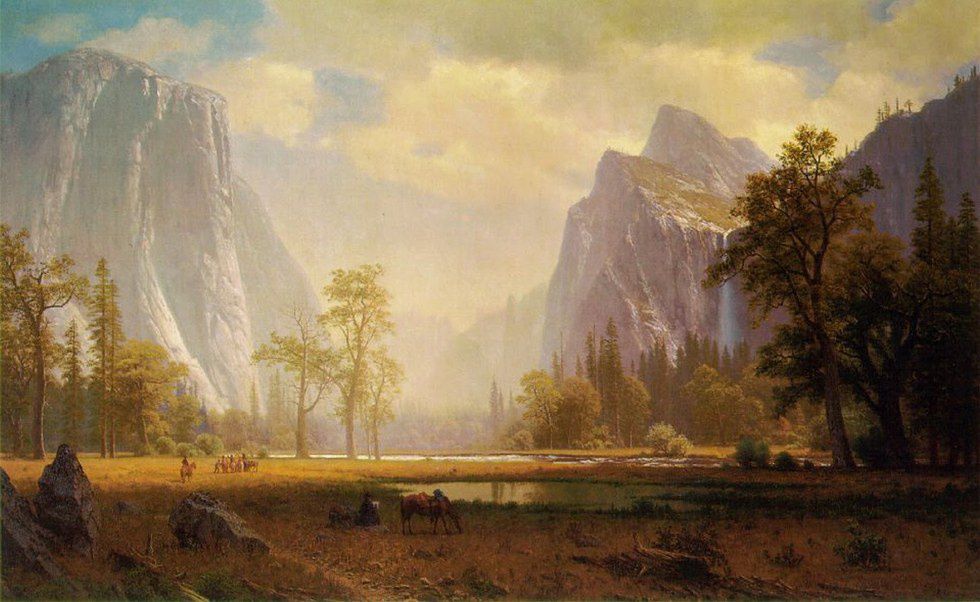

Fig. 6. Albert Bierstadt, Looking up the Yosemite Valley, 1863-75, Oil on Canvas, 36” x 58.5”. The Haggin Museum, Stockton, CA.

The cliffs that Romantic era, Sublime painters, such as Albert Bierstadt, created, certainly appear to have inspired Dali’s rendering of landscapes (See fig. 6.). The cliffs in both Dali and Bierstadt’s work are painted in atmospheric perspective, which gives them a hazy, grand, looming appearance.

Fig. 7. The Pulcino della Minerva, Giovanni Bernini and Ercole Ferrata, c. 1667, Marble. Piazza della Minerva, Rome.

Finally, the elephant carrying the obelisk, a recurring image throughout a lot of Dali’s paintings, is a very obscure reference to The Pulcino della Minerva by Ercole Ferrata and Giovanni Bernini (See Fig. 7.). The obelisk was originally discovered in Egypt, then shipped to Italy, where Pope Alexander VII held a competition for the base of the obelisk (Pollett). Pope Alexander stated that he wanted the obelisk to represent divine wisdom and holy knowledge, so when Giovanni Bernini submitted several designs for the base, and one of them was an elephant, Pope Alexander knew exactly which to choose (Pollett). He saw the elephant as representing fortitude in the face of intellectual/spiritual adversity, and that the obelisk should be supported by something that symbolized stability and security of knowledge. The base of the marble statue even says, “A strong mind is needed to support a solid knowledge,” significant because without the strength of the elephant (fortitude of faith), the obelisk (knowledge) would not be able to exist. It stands to reason that Dali, with his passion for learning, would really connect with the symbology of the elephant carrying the obelisk. It also is not a surprise that Dali’s art seems to draw inspiration from so many different periods of art before him; he took pride in his intellectualism. For example, his studies of Freud started even before he subscribed to the Surrealist movement (Biography). Reading up on theories such as free-association, psychoanalysis, and sexuality, Freud inspired a lot of Dali’s artwork as well as his philosophy, even helping him come up with the paranoiac-critical method (Ades, 72), without which, Surrealism would not still exist.

Salvador Dali, with all of his quirks and knowledge, seems to have successfully inspired generation after generation of artists to express themselves in a more poetic, symbolic, personal way. For example, Neo-Expressionism, a form of art popular from the 1980s onward, seems to draw significant inspiration from Surrealism, and therefore Dali. The symbolic, sometimes difficult to interpret, paintings of Neo-Expressionists, show dreamlike scenes of purely emotional linework and form. The methods used by Neo-Expressionists are also similar to the automatism and paranoiac critical method from the Surrealist movement. Just as well, Neo-Expressionism is all about being in the emotional state that you are putting on the canvas, and the varied emotional reactions of each viewer. In addition, Surrealism itself has yet to die out; many find the psychological expression that comes with Surrealism to be therapeutic as well as aesthetically pleasing. Classical Surrealists are still around and producing paintings; Carlos Solis is a prime example.

Fig. 8. The Fall of False Revolution, Carlos Solis, 2012, Oil on Canvas, in the possession of the artist.

Here are the book sources I used, in case you wanted to check them out:

Ades, Dawn. Dalí and Surrealism. New York: Harper & Row, 1982. Print.

Caws, Mary Ann. Surrealism. London: Phaidon, 2004. Print.

Robert Descharnes, and Gilles Néret. Salvador Dalí, 1904-1989: The Paintings. Köln: Taschen, 2001. Print.

Pollett, Andrea. "Curious And Unusual - 'Minerva's Chick'" Curious And Unusual - 'Minerva's

Chick' Virtual Roma, n.d. Web. 10 Apr. 2015.

Raimondo, Joyce. Imagine That!: Activities and Adventures in Surrealism. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2004. Print.

Waldberg, Patrick. Surrealism. New York: McGraw-Hill Book, 1966. Print.

And here are some additional sources you can check out, if you're interested:

"Salvador Dali - Biography." Bio.com. A&E Networks Television, n.d. Web. 10 Apr. 2015. http://www.biography.com/people/salvador-dal-40389...

Palomo Alarco, "Colección Permanente Del Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Visual Tour."Colección Permanente Del Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Museo Thyssen, n.d. Web. 17 Mar. 2015. <http://www.museothyssen.org/thyssen/visita_virtual...

ene_45a_7077%29%3Bwait%28blend%29%3Blookto%28110.353%2C0.191932%2C0%2Csmooth%28100%2C20%2C50%29%29%3B>.