I’ve been thinking lately.

I feel like a lot of people find that hard to believe, since liberals, especially young liberals, are reactionary and impulsive. It’s true that sometimes we don’t meditate before we act, and that’s as much a response to a tumultuous time in politics as it to the fact that we’re often trying to juggle academics and other responsibilities. I digress.

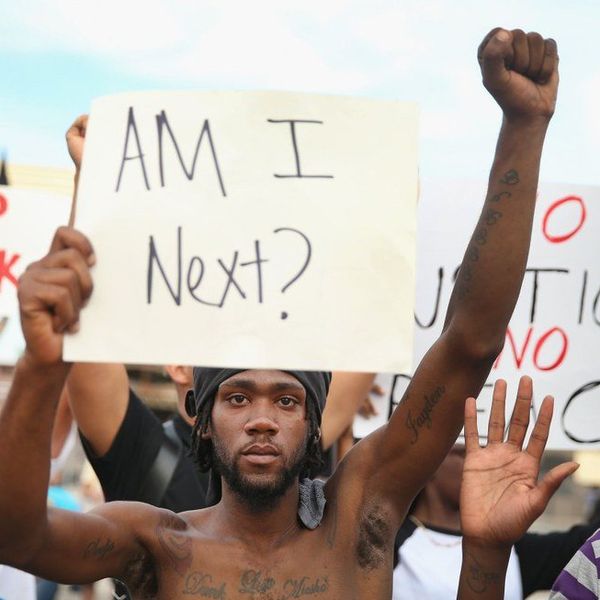

I’ve been thinking lately about the kind of ‘Resistance’ I’m a part of. For a lot of people, the federal government is engaged in actions that target their communities specifically–– women trying to find affordable reproductive aid, Muslims and other immigrants trying to enter the country, LGBTQ individuals who may be discriminated in the workplace and at home,... and so on. A few articles ago, I mentioned that a goal of the recent protests should be to include as much diversity and plurality as possible, incorporating these other groups into a large aggregate protecting one another. Yet, often when I have been marching of late, I notice that the events are still formed from mainly straight, white people, many being male. There might not seem to be anything wrong with such a composition when everyone is likely to be affected by the current government’s agenda, but not everyone in the United States will be affected in equal proportion, as we have seen already with the travel ban on several Middle Eastern countries, the planned defunding of the ACA, and the cabinet appointment of charter school advocate Betsy DeVos. If we as activists want to claim to be above the -isms associated with the Trump administration (sexism, racism, fascism), we have to be intersectional about our demonstrations. Plus, when the organizers chant, “Show me what diversity looks like”, it would be less uncomfortable to shout back, “This is what diversity looks like!” if it weren’t fifty or so white men and women responding back. And this isn’t to say protest leaders should pity nor actively ‘seek out’ women, minorities, and immigrants; but as I’ve discussed previously, if those people seem to be left out of demonstrations, it’s worthwhile to explore why that is.

And all this got me thinking about the safety pin, a symbol I still wear everyday despite the growing criticisms that such icons of attention are meaningless, if not self-aggrandizing, trinkets worn by white, trendy activists trying to stir controversy and fit in. I can’t deny my own misgivings about wearing the metallic pendant, and it isn’t helped by the fact that I freeze whenever someone casually asks, “What’s that safety pin mean?” There should probably be a rule that if you can’t adequately explain what your symbol stands for in a minute, you might need to reevaluate why you’ve chosen it in the first place.

Here goes: The safety pin movement was (reportedly) conceived in Great Britain after the Brexit vote led to an increase in hate crimes across the country, and citizens sought to identify solidarity with foreigners and minorities. In the United States, as the election campaign reached its fever pitch in November, the safety pins skipped across the pond as a simple way to combat bigotry: Wearing one meant that the individual stood in solidarity with and would protect those in danger due to gender, sexuality, race, disability, religion… At least, that’s what the pin represented for the wearers. And despite everything, those who donned the safety pin seemed to be predominantly white ‘allies’ of those communities mentioned.

So do I think the safety pin movement is another form of “slacktivism” meant to symbolize intersectionalism while essentially doing little to nothing. Yes. The safety pin by itself isn’t going to do the work necessary to cross bridges between different people, communicating to minorities and discriminated groups that you’re there for them. The safety pin by itself may not identify you as a safe person in the event that someone is being harassed or threatened for their identity. And it doesn’t, on its own accord, make you a good activist and person. Both of those distinctions take effort and dedication.

So why might people, especially white people currently still wearing safety pins–– as rare as they may be considering the criticisms levied against the fad–– keep the emblems pinned on? I advocate for the movement as a way to remind citizens of their responsibility those who are discriminated and disadvantaged. If the safety pin comes off more as a symbol to the self, then let it be utilized more as a tool for empowering the self towards action for others. And I don’t mean the kind of support that involves someone outside a group coming in and deciding how to run things to best help these ‘poor victims’. The distinction between informed support and saviorism is easy if you remember that the former involves asking a group and listening to their advice on how you can help them achieve their goals of representation/equality. White, upper class men wearing safety pins: Think of the instrument as a silver spoon instead, except instead of in your mouth it’s on your clothing. From there, be aware of situations you’re facing as an activist and just in everyday life, and how you can be respectful and responsive to other communities and work towards legitimate action. Instead of emailing a Senator, call them or show up to their office with a group. Contact your local mosque and ask how you can stand with Muslim citizens. Donate to organizations like the ACLU and Planned Parenthood, but also reach out their local chapters to volunteer if there’s need. And if someone is being physically or verbally assaulted, stand up for that person, against the attacker, recording the incident and offering assistance to the individual in danger.

I’m not going to rally behind a ‘re-emergence’ of the safety pin as a code for enlightened white activists, no. But many of us do forget, in our reactions and impulses, to accommodate for other groups and their experiences. Whether it’s a pin or some other adornment, you can instruct yourself to remember your cause for standing with a diversity of people, not out of white guilt or sympathy, but because we’re all people with a stake in this country’s future, and we deserve the respect and fairness given to us by the laws of this land.

If after all this, there’s something essential I’ve forgotten to mention about the topic of the safety pin movement, don’t hesitate to let me know via comment or Facebook message. At the end of the day, I am a white activist myself who doesn’t hold the complete puzzle, only certain pieces I’ve assembled. I know I myself must get better at reaching out to other people, and holding myself accountable when I do not help create diversity and cross-cultural exchange. All I really ask at the end of the day is that those of us that keep using accessories like pins to represent safety recall that they must work towards safety through shared community and conversation.