The definition of family is a basic social unit consisting of parents and their children.

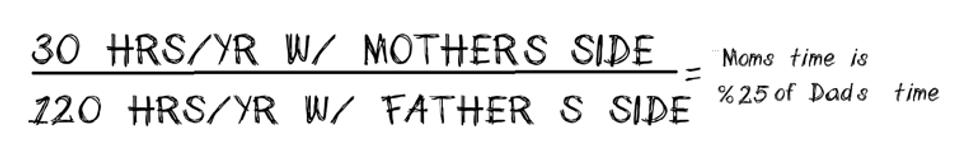

My parents are divorced. The Irish blood on my mother's side of the family has less of an effect compared to the Cuban blood on my father’s side. To explain this, I’ve written an equation for you.

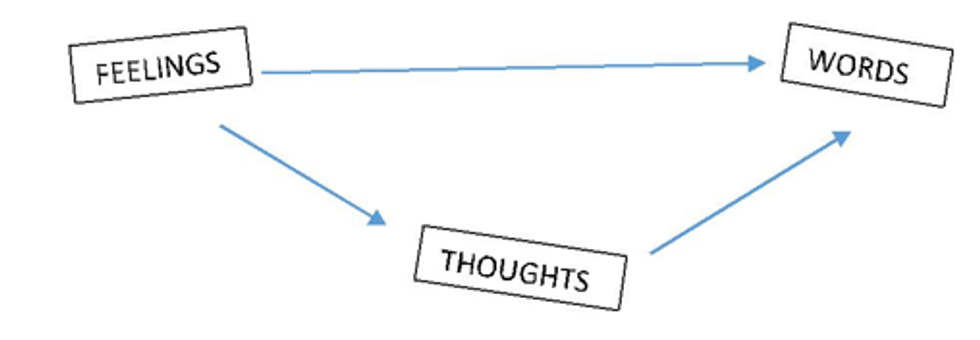

Sometimes, I feel like I hate Ireland, but that’s improbable, because feelings can’t exist without words. If I can’t describe why I don’t like Ireland, then I’m not feeling anything.

***

I attend school at Farmington Elementary. There’s a spiraling tree that looks like an octopus in the front yard and windows with art. My classroom is at the front. The other classes have normal desks with white floors but ours have carpets. Every Wednesday, we do math packets. I get annoyed by the staples. It’s hard to tell exactly what angle they are and I claw them out with my fingernails. My hands bleed. My teacher tells me to go to the nurse. I put on cream. That’s how I get out of class.

***

Dad had a friend named Vanessa from Ecuador. Black lipstick. Twenty-seven years old. Dad was forty-three. She worked nine hours a day at the Laundromat and arrived in the country on a truck. Vanessa came after Mom left. She sat in the same booth with us at the diner. We drew on children’s menus together sometimes, but Vanessa was not Mom.

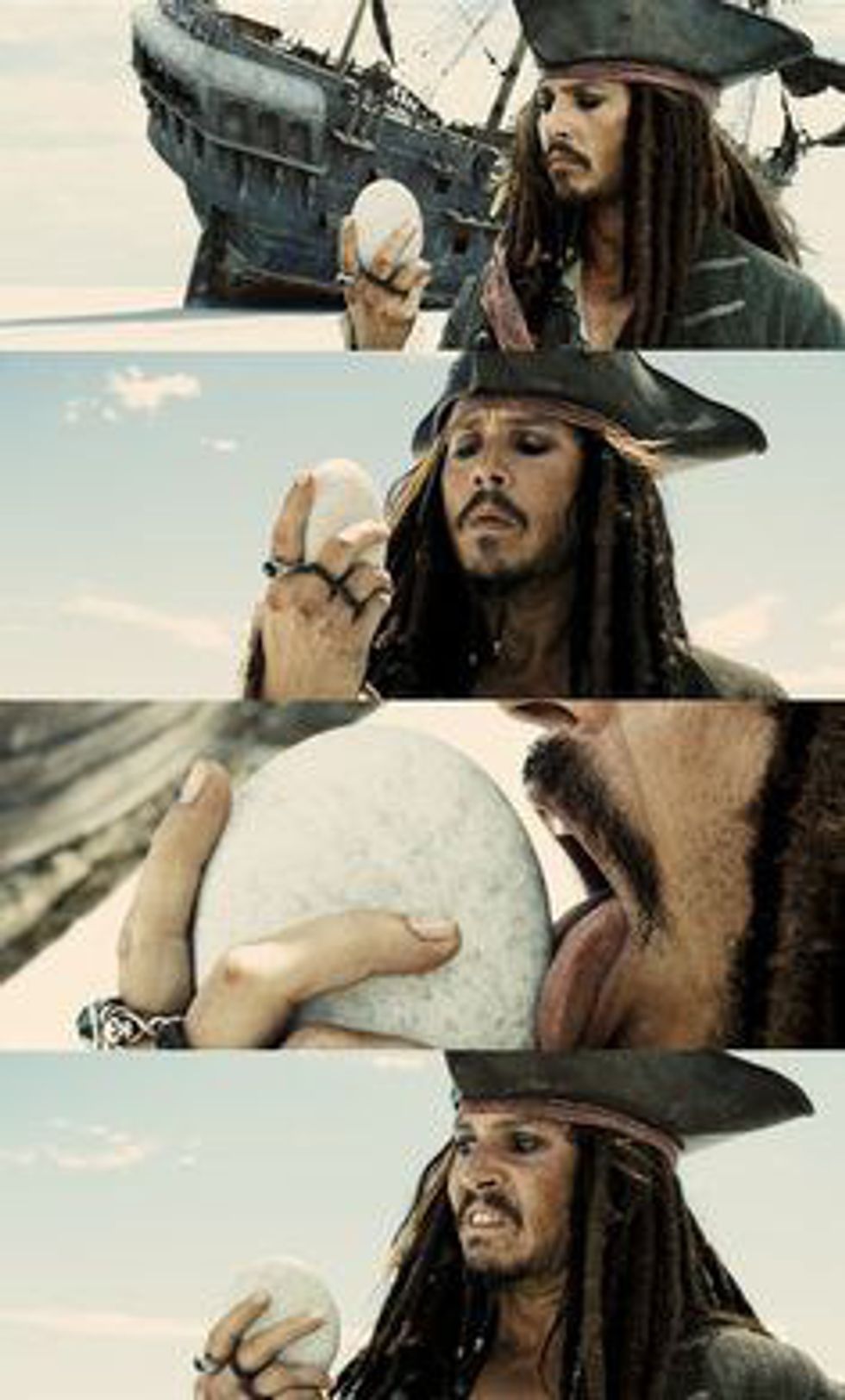

“Show Vanessa,” my father would say when we sat at the diner. “Show Vanessa how you draw the moon."

I’d smile and pick up the crayons. I picked up four at a time, bundled in my fist, and tried to hold onto them. The crayons went in all direction. Sideways. Slantways. All sorts of way.

"That’s nice,” Vanessa said, trying to smile.

Mom would stay home to care for me. Now she's left, which is something called divorce. It works like long division and makes families smaller. After my mother left, I allowed myself to feel sad. Then I researched divorce. Divorce happens often. Now, we are a single-parent household.

***

Dad and I look for grass people together. Dad was a grass person once. Now he's a professional. He came to this country in a truck as well. Now, he computes numbers with eight digits and wears a tie every morning. There are still grass people who wait outside in the morning to be hired. If you drive by the Dunkin' Donuts, you can see them down Main Street. They have heavy bags full of tools and sad faces like Easter Island heads. Dad helps them. After breakfast at the diner, we drive to hire them. They tile our floors and sweep leaves off of our patio. For every hour of work, Dad gives them fifteen dollars and Aquafina water bottles.

“I worked hard once,” my father tells me. “Now I give something back...”

One day in July, we sat outside in our backyard where there were three grass people. There was a fat one, a skinny one, and a bug-eyed one. The air had a wet-dry feeling. That’s what I call it when it’s not raining, but it’s still wet.

“Little man, little man,” the fat one said, ruffling my hair. “You go back to school soon, meet lots of girls…”

I smiled, but didn’t say anything. There were only two girls in my school and one was in a wheelchair and could only talk with a computer. Dad stood nearby. He doesn’t always speak. He just nods a lot.

"Well, they'll have to make room for another lady," my Dad said. "He's getting a new nanny very soon...."

"Who?" asked the skinny one.

"Vanessa Garcia's mother. Her name is Rosita. She works at the Laundromat. I'm doing them a favor. She’s going to live with us during the week and go home on the weekends.

"Garcia?" said the bug-eyed one, smiling, raising his eyebrows. "Vanessa? She is the one you--"

My father coughed. I asked him if he was sick.

"I'm fine," he said. "What do you think about lending these guys a hand, buddy?”

"No, no," laughed the fat man. "College. You go to college, my friend..."

I giggled into my hands. I rocked back and forth. I brushed my hands on the stone wall. My fingers were chipped. I'd picked at dirt. I imagined a new renovation on my house where there would be enough rooms for one hundred grass people, and in the morning, we'd gather for a big breakfast. Every night, a big bonfire. We’d play the guitar. We’d tell stories.

***

Rosita arrived on Sunday evening. I hid in the hall, cautious, waiting. The doorbell chimed through our house. My routine was planned. I’d rehearsed this and had planned to be playing Legos.

Dad welcomed her inside. My first impression was a great tortoise standing in our doorway, wearing a furry coat. Her face was sagging and she made me think of a candle melting.

“You don’t have to take a taxi, y’know,” my father said. “It’s our hospitality…”

“I pay,” Rosita said shortly. “I take care of myself.”

They walked into the dining room to discuss pay. I crept into the living room. I hid behind the candelabra and ducked beneath the filing cabinet to spy on them.

“He’s a handful.”

“Yes. Sweet boy.”

“Well, he can be a handful.”

I poked my nose out. She was smiling at me, her cheeks perched up in high dimples.

“You come. It’s okay…”

I walked toward her.

“My daughter tell me about you. You know Vanessa?”

I said nothing. I watched as she reached into her pocketbook. She pulled something out. It was a large, white book with a cross on it. There were cartoon people on the front wearing robes standing with lambs and lions and snakes.

“I bring you present. Jesus.”

I bit at my fingernails and took the book. I looked around at my Dad, Rosita, and the chandelier on the ceiling. Then I giggled and sprinted out of the room.

I dashed down the hallway. I leapt down the carpet like a long jumper. Then I landed hard on my bed, shaking the whole post. I kicked the wall, still giggling, and cradled Jesus.

In the other room, Rosita was laughing. So was Dad.

***

Rosita was very different than past nannies I’d had. When I woke up on the first morning for instance, there’d be no cereal. She'd be downstairs watching television.

"Rosita," I said. "I need cereal."

"You are big boy," Rosita said, her face pressed to the pillow. "You pour milk..."

I glanced around, unsure, waiting for somebody else. “Okay…but I need cereal…”

“You go. You learn. I’m here. I watch…”

In the kitchen, I tried to unscrew the lid from the cereal tubs. They wouldn't budge. I twirled the cap hard, cringing, trying to flex my fingers. Whenever I pressed hard, the plastic grove sliced my hands.

“What is this?" Rosita said

When she walked in, I was curled up in the corner. There was Trix and Captain Crunch all over the floor, pouring out of tubs like colored, buried treasure.

“Pick up,” she said.

I did not.

“Pick up. You are big boy.”

I just stared. In school sometimes, I wouldn’t want to do my work. I’d throw a tantrum in the corner and then they would send me to the principal’s office and my Dad would pick me up and take me out for dinner. I stared down Rosita. I looked at the cereal and imagined Lucky Charms asteroids and meteor showers of Captain Crunch.

“We sit,” Rosita said calmly.

A minute passed. I imagined a galactic war on the kitchen floor. The Captain Crunch armada was descending into the Milky Way and blasting sugar cannons at the Lucky Charms pirates.

Then I leaned back and groaned, banging my fist against the cupboard. I kicked my legs. I crushed cereal.

Rosita grabbed my hand, not hard, but enough to stop me.

“Pick up,” she said.

“No,” I snapped. “I want breakfast.”

Rosita sighed and bent down on the ground. She started to pick up pieces of cereal herself. I watched from the corner.

“Go to room,” Rosita said. "You no care.”

She moved around the floor, picking up pieces like a human vacuum. I sat there, my face hot and embarrassed. I hadn’t been excused yet, so I couldn’t leave.

“Go," Rosita said finally.

I reached out and grabbed a single handful of Captain Crunch. Then I ran out of the room and ate the purple pieces first and then the green. Rosita didn’t talk to me for the rest of the day. I was glad.

***

The best video game is called Super Monkey Ball. The object is to guide monkeys in glass balls across platforms. They fly through windmills, outer space, and across colored blocks of all shapes and sizes. One day, I was playing a level in which the monkeys had to traverse a dodecahedron rotating at seventy miles per hour. For the harder levels, I draw them out with a ruler to figure out how fast I should be going. Then Rosita came into the room holding a vial of pills.

"It’s a beautiful day," she said, popping one. "Why don’t you go outside?”

'No..." I replied.

"No, no. This no good for you.”

Rosita sat down beside me and picked up the controller. I reached out to stop her.

"I show you," Rosita said.

The monkey bounced across the platform, soaring, landing on a power-up. She cleared the stage. She didn’t do it well but it was a passable high school and not that bad. It made me angry.

"Now go outside," she said, handing the controller back.

I couldn’t do anything else so we left. I went outside to play on the swing set and imagined Rosita in a glass ball falling to her death like a monkey.

***

"You aren't eating your ice cream," my father said.

We were at Friendly's. I spooned the monster ears off the side of my sundae. Rosita had gone home for the weekend. I was glad because she was beginning to irritate me. I enjoyed going to Friendly’s because it meant that I could eat ice cream and draw on the placemats and talk to my Dad about the New York Stock Exchange. I don’t know what this is, but I bring it up so we have things to talk about.

"How's school?" my father said after a moment.

"Yes," I said sharply. This is not the correct answer but it’s what I said. "They put my name on the bulletin board for good behavior.”

They hadn’t, but I said this so we had something to talk about too. My father smiled at me and asked, "How do you like Rosita?"

"She's fine," I said. I scrunched up my face, pretending to think. "Was she...was she wearing sandals or sneakers this morning?"

"Son," my father said. "That’s off-topic."

"Okay," I laughed. "I was just...I don't know why I said that."

"Why do you click your legs together?" he asked.

I looked down at my legs. I tried to stop, but they shook anyway.

"I don't know. Mom let me.”

"Well," he replied. “People are going to stare. Do you like when people stare at you?

I did not. It made me anxious and made me think I’d done something wrong. In fact, there were a lot of people staring now. I wouldn’t have noticed them if Dad hadn’t pointed them out, but they kept looking at me. I tried to eat my ice cream, spooning up the cherry, swishing the liquid chocolate with a spoon. But then I thought of all the different eyes looking at me from so many different angles, and for some reason, this bothered me greatly. It bothered me so much, that I banged my legs against the table.

“You stop that,” my father said.

I couldn’t help it. More people were staring now. I shook the whole table and rocked the booth a whole foot to the right.

“Stop,” my father said, leaning forward. “It’s all in your head…”

That’s when I started to cry. You never know when you’re going to cry, but it just happens and everything comes out wet. The waitress walked over with her little booklet, flipping through it. I thought more ice cream would make things better but my Dad started talking to her first.

“Is everything all right?” she asked.

“Yes, we’re going,” my father said, snatching his coat. “It’s fine. I have it under control…”

A few minutes later, we were sitting on the bench outside the restaurant. They’d put my sundae into a paper cup, but I wasn’t eating it. My Dad was sitting next to me. In front of us, there were mosquitos by the lamppost.

“I’m sorry,” I said. I didn’t know for what exactly, but this was so we would have something to talk about.

“It’s okay,” he sighed. “But promise, you won’t act up anymore….”

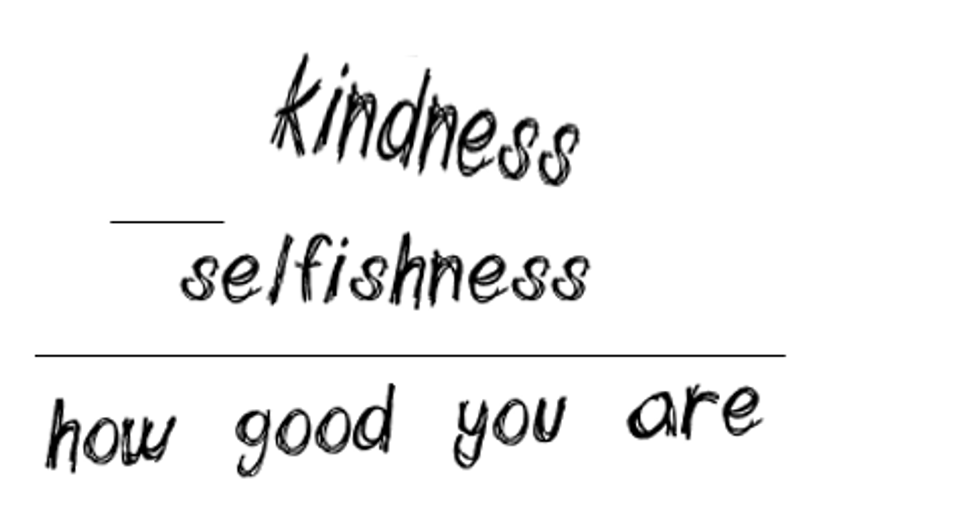

When you’re crying with your parents, you always feel like you’re floating in outer space. The world outside seems quiet, but at the same time, there’s a weird, silent buzzing. I read articles online. They said people like me can’t love because we’re missing something in our amygdalas or something. I don’t think this is truth, because I can feel love. I just haven’t in a long time. The love I felt for my mother was very different than my Dad, but this is okay, because we’re a single-parent household and I imagine the love is different.

One time when I was little, I’d gone to a balloon festival and skidded my leg running to a chair. That was when my mother had taken me to a tent to put on a band-aid. When I was with my Dad, I sort of felt something similar to what I felt then, but it wasn’t the same. This was because I’m not allowed to think about my Mom now, so I don’t have the catalyst for the same reaction. This is why it’s important to make new equations to replace the old ones.

“Up on the bulletin board, huh?" my dad asked, smiling. “Come on,” he continued. “Let’s go home…”

***

Every day after school, I'd bolt to my room and lock the door. No monkey ball. Just sleep. Then Rosita would come upstairs and knock on the door. At this point, I would have really bad thoughts about her and wish she was dead or that she would get hurt very badly in a car accident.

"You sick again?" she’d ask through the door.

I never responded to her. I was reminded of documentaries I had watched on television. If you didn’t move in front of bears, they may not attack you because they were not provoked. Rosita was not a bear, but I think very strangely when I am anxious. It didn’t matter because she always mumbled things in Spanis before she left anyway.

Eventually, I ran out of textbooks to read. I thought of arithmetic, counting the swirls on the ceiling. Sometimes, you get very lonely that even things you find enjoyable are no longer fun because you can’t remember why you liked them. This was one of those times. I remember the room felt very dark even though there was sunlight and I wanted to hit something.

Then I heard Rosita downstairs. She was singing in Spanish, her voice wafting up through the floorboards. There were fifteen rooms in our house, plus a swimming pool and a shed. I realized we weren’t on the same floor. I don’t know why, but this made me cry, so I started sniffling into the blankets. I must have been loud, because the water running downstairs turned off. I clutched my blanket as Rosita's footsteps echoed up the stairs.

"Chico?"

She stood the doorway. My lips shook up and down.

"Do you want to do dishes?”

"No,” I said quickly.

She walked over and sat down. I tried to stay still, rigid, but something happened to my throat. My voice croaked, hoarse and broken, and I started crying into her lap. I felt very embarrassed, because she was my nanny and this wasn’t her job. I wouldn’t have even done this in front of Vanessa, even though my Dad says she’s very compassionate and wants to be a psychologist.

"You don't need a reason to feel sad. Let me wipe your face..."

I didn’t think this was true. If you were feeling bad about something, it was your fault for allowing yourself to feel that way. That was what my father said. If you let yourself feel a certain way, then you were a slave and not in control. That made me upset and I squealed and kicked the bedpost hard.

"I want my Dad..." I snapped. “I don’t like that he works in New York…”

"I like your father too," Rosita said, smiling. "He's going to help my daughter..."

***

Every weekend, my father would leave money in a rubber band on the counter, and Rosita would take me into town. We would buy chocolate gelatos, which we ate as we watched ducks in the park. I soon learned that Rosita enjoyed lots of things, like shopping and American movies and watching me play on the jungle gym in the playground. She also enjoyed weddings, which I probably wouldn’t be seeing ever, because I didn’t think anybody would marry me. They had told me this several times in my classes, and my father had sometimes told me this as well.

In town, there was a used bridal gown shop near the church with skinny mannequins in the window. They had scared me often, because they had no eyes and looked like demons with their skin peeled off. Rosita didn’t mind though, and took me inside one afternoon.

There were racks of old dresses that looked like ghosts there. Rosita reached down into a cardboard box on the floor. She pulled out a strand of silver tinsel and draped it into my hands, letting it flow through my fingers. I do not like things that are hard, because they remind me of sandpaper and feel like they are rusting my skin. I much prefer things that are soft.

"I was going to get married once," Rosita said, staring at one of the dresses. "There was going to be a big wedding.” She smiled at the dress, seeing something I wasn’t. “But there'll be another wedding soon..."

She picked up the tinsel and draped it on my shoulders. I strutted up and down the aisle like one of the models on the pageant shows where they answers questions about things that are happening in Africa. Rosita laughed at me, and clapped my hands to applaud my performance.

"A big wedding," Rosita said again. "You'll be there.”

"Who's getting married?" I asked, taking off the tinsel.

She winked at me and said, "It’s a surprise.”

***

My father had started to make me think of a magician. This is because magicians always get away with everything, and don’t have to explain their tricks to their audience. Magicians saw people in half, set rings on fire, and made women disappear in a crack of smoke. They never explain how they accomplish their feats, and I always found this stressful, so I never went to magic shows. I like when things are explained, so I don’t have any questions and don’t have to think about other possibilities. But the more time I spent with Rosita, the less time I spent with my dad, and it started to make me very anxious.

In our living room, we had pictures on the wall of our family, which were taken before we become a single-parent household, so they included my mother. When I arrived home from school one day, I discovered that my father had taken these pictures down. I checked again in the afternoon, and discovered that they were still missing. I didn’t ask my father about it, just like I’d never asked him many other things. I never asked him if it was okay to think of parents who had been removed from equations, or what the catalyst had been to remove my mother in the first place.

We sat at dinner and made scattered attempts at conversations. He talked about signing me up for sports, and I picked at peas and carrots with my fork. I laughed when he laughed, and smiled when he smiled, and that reassured me that we still had something in common.

***

"Does my mother ever talk about me?" Vanessa asked, buttering her toast one morning. “Rosita?”

My father’s girlfriend had joined us for breakfast. My father was out talking to some grass people on our deck, who were busy sweeping leaves off our patio. For this, they were paid much more than they would have been paid at other houses, because my father is a talented businessman. At the table, I was eating scrambled eggs and bacon, which I had arranged onto separate sides of my plate. I did this because I don’t want the colors to blend, even if they all blend together in my stomach and turn brown. I know this isn’t very logical, but I find the presentation to be very important. Vanessa didn’t seem to find it very important, because her eggs and bacon were blended all over her plate like a collage. I tried not to look at it, because it was very uncomfortable to see, but there were other reasons I didn’t like to look at Vanessa. She had been very nice to me that morning, and asked me all sorts of questions about school, but I still found speaking to her very strange.

"I don’t know…” I said. “Is Rosita supposed to talk about you?”

She paused, taking a bite of her toast. "I need you to tell me if my mother says anything about me, especially if she says something about your dad.”

There was a crash outside. Some landscapers had just cut down a tree and its scraps lay around our yard. I saw my father clap one of them on the back, his own stained with sweat.

"Got it?" Vanessa said, staring out the window as she watched the scene unfold. "You have to tell me what my mother’s thinking, because I can’t talk to her myself. That’s just how it is with us.”

***

Last night, I had a dream that I was inside of a glass ball. I was at the tip of a long runway surrounded by a purple haze that went on and on forever. I started to spin. I blazed down the colored ramp, twirling in circles, and everything became a blur as I fell like a monkey. Then Rosita came rolling by, and she was wearing a white bridal gown. Through the glass, I could see her face, and she was very scared of falling into the dark abyss. Then my Dad's ball came rolling in. It knocked into Rosita's ball hard, nailing her like a bumper car. She went off, gone, falling into oblivion. I woke up with my model airplanes spinning from the ceiling and my father snoring in the next room over. My poster-boards were all over the room, where I had computed all of my monkey ball levels. It was October now, and I didn’t know why, but I was beginning to get very scared.

***

"Rosita," I asked the next morning. "How much longer are you going to be my nanny?”

Rosita was watching television in the living room. She liked to watch game shows, the weather channel and also these soaps where everyone spoke Spanish and seemed to be involved in organized crime, and where the nurses dressed like strippers. I didn’t need her help with anything. I’d learned to pour cereal by myself, and I’d learned to pour milk, and I’d even learned to vacuum. None of these were reasons that I had approached Rosita, because I had something else on my mind entirely.

“What do you want?” she asked quietly. She was sitting on the couch, her hair tangled in knots. She looked very, very tired.

"I...was wondering...” I started. My fingers tightened in my fist, digging away at my skin. “If you were going to stay with me much longer?”

“What do you mean?’

“Will you still be my nanny? I wanted to know when I’ll be alone with my dad.”

Rosita frowned and raised her head, looking me up and down. There was something different, and she wasn’t smiling at me like normal, so I started to wonder if she was ill with a fever. I immediately regretted asking because I thought it made her mad. Now that I had offended her, she was going to move away and never see me again, and then I would be stuck with my father in our single-parent household. I wanted to blend into the shadows on the wall and disappear.

"Your father talk about Vanessa?" she asked.

"I…I don't know,” I stammered. “But I was wondering—"

"They no see each other now,” Rosita said, speaking as if I wasn’t there. “No talk. No nothing…”

She looked scared and frightened. I had never seen adults like this, and I especially hadn’t seen Rosita like this. I shook my head, and tried not to tear up, because none of this was very familiar to me at all. I didn’t understand why Vanessa mattered, because she had nothing to do with this equation at all. The relationship between my father, myself, and Rosita was simple to understand. Rosita watched over me, and my father paid her money, and my role was to be nothing but the compliant. Vanessa had no business with any of that, and I struggled to decide if there was a variable I had missed somehow.

Rosita got up and winced, cringing from a pain in her back. I watched as she reached over to the coffee table and picked up the children’s Bible that she had given me as a gift. A few weeks ago, she had read me the stories of Job and Adam and Eve. I couldn’t see from that far away, but I knew that she had settled on a picture of Satan. He was the big, elfish creature with red horns and a beard who carried a pitchfork. Underneath the Earth, he tortured people who were bad and spun them around on a wheel at a hundred miles per hour until their skin peeled off. I don’t know why, but when I looked over at the shining pitchfork, I imagined I would be meeting it very shortly. I imagined that I was bad, and that my father would join me as we boiled together in a searing pit of magma.

"Crazy house,” Rosita said quietly, staring at the cartoon devil in the picture. “I live in crazy house….”

***

“No more tantrums, look at that,” my father said, clapping me on the back. “Proud of you, champ…”

We were standing out on the baseball diamond. My father had taken me on a weekend excursion to the park, and was coaching me on how to angle my body for the perfect pitch. There was a very specific way to throw a baseball, based on your body and the velocity of the pitch. He wanted to get me trained for Little League again, so I would be able to stay on the team and not have to leave for striking out and not participating as much as the other children. That had been in first-grade, but now I was much older.

“Don’t get down on yourself,” he said encouragingly. “You’ll get it.”

I watched as he walked off to grab another bat in his bag. The sun was setting. The bleachers were casting a shadow on the dirt. I stared at first base, picking at my nails and looking up at my father. He was hunched over, digging into his bag.

“I should bring Vanessa sometime,” he said, searching for the bat. “She loves baseball, did you know that? You know, they don’t have stadiums in Ecuador…”

I started to walk over to him. I didn’t know why, but I felt pulled over to him by a magnetic force. It was very strange that I did what I was about to do, because I was very happy to be playing baseball with him. It was also a very hot day and I was getting tired. There might have been more to it, but I don’t remember. The point is that I walked over, and hugged him the same way I hugged Rosita. I had rarely done this to my father, mainly because I had never gotten close enough to do it. When my mother had washed me in my bathtub for example, he would walk in wearing his business suit and see me playing in the soapy water, and he would never touch me at all.

Now, my face pressed against his belt. There was the shape of muscle, the touch of body heat. In the distance, I could hear children playing in the playground. I pressed in harder for a moment, and then I brushed off. I stared at him blankly, waiting for him to offer some kind of response to what I’d just done.

“Why did you do that?" my dad asked bewildered.

He stared at me, offering the baseball bat. It was the same look he’d given me at Friendly’s three months ago, and I regretted my actions immediately. It was not time to give a hug, but rather time to play baseball.

“I don’t know,” I said quietly.

And with that, I took the bat and walked back to first base.

***

“Your mother’s seemed tired lately,” my father said at the diner a few days later. “Rosita’s been a lot slower around the house.”

“I’m not Rosita,” Vanessa replied, rubbing her belly. She’d gotten a little fatter recently, and I imagined she was eating more than she should have been.

We were all sitting in the booth at the diner. I played with the crayons, going through the Sunday ritual of navigating a cartoon dalmatian to a firehouse on the menu. I had done the math and there were two possible ways to get there and seven others that led to a dead end. This was comforting, because Iknew how many options there were, it was a matter of trial and error until I found the solution. Vanessa was sitting there, quiet, doodling on the other side of the page. She had drawn a smiley face, and written her name over and over in cursive. As my father spoke to her, she traced over her name with a purple crayon until it became hard to read.

“How’s work?” my father said. She wasn’t replying to him very much, and he seemed to be searching for things to talk to her about.

“Fine,” Vanessa replied, tracing over her name.

“Well, do you want the check?” my father asked after a moment. “Do you want to go now?"

“I’m still eating. See my food?” She indicated the eggs on her plate. “You want this. You want that. You’re always moving everyone so fast.”

My father just stared. “So…when you finish your eggs then?”

“No,” Vanessa said stiffly. “I’ve lost my appetite. Please drive me home.”

***

The next morning, I put a very careful and calculated plan into action. I had devised it over the week, and I was certain that it would work out perfectly. I stole an electric can opener in the kitchen. Right after my father left for work, I wrapped the chord up and dropped it into a cardboard box. I went into our living room and took the spare universal remote, a Keurig, and a laptop charger. It was hard to consider this theft, because they were my family’s possessions, and I was technically a part of my family even though I was a child. I dumped all of my things into a cardboard box. It had been full of packing peanuts at one time and used by my father to give some kind of expensive vase to my mother. Now, it was going to be used for something else. I left the cardboard box in my room and marched downstairs, to discover Rosita sitting in the living room. She reclined on the sofa, watching soaps when I walked in.

“You are buzzing all over the place today,” she said, smiling at me.

I smiled back, and asked her for my special pair of Fischer-Price scissors. These were purposefully dull so I wouldn’t cut myself. I didn’t want the shears, because they’re very dangerous, and I could slice my fingers off and leak blood everywhere. A few minutes later, I found some old Christmas wrapping paper in the closet. I tore off a big sheet and set to wrapping up the cardboard box. I wrapped it layer over layer, precise, making sure that none of the brown showed through. I kept strands of tape on the side of the box for good measure. I had decided to give some of my father’s possessions to Rosita. That way, she’d stay with me for the whole summer, and I wouldn’t have to be left alone with my father. I knew she was very much in-between right now about staying with us, so I thought this would encourage her very nicely.

Rosita didn’t have very much to her name. Every week, she brought a pillow and a pocketbook to her house, and seemed to be able to carry all of her possessions in one trip. If Rosita thought my father was bad for ignoring Vanessa, and that my family was therefore bad as a collective whole, this would surely set her straight. I had read the Bible now, and learned that bad people wouldn’t have given away remotes to poor people. If I gave electronics to Rosita’s family, she would be willing to stay with us, and I wouldn’t have to spend more painfully awkward time in my father’s company. When I was done, I locked the box in Rosita’s closet, and planned to give her the presents before she returned home that Friday evening.

***

That night, Vanessa came over with Rosita to visit my father. She sounded much happier, and Rosita did too. I listened how they gossiped in Spanish downstairs, wafting up through the floorboards into my room like loud, chirping birds. There was lots of drinking, and lots of laughing. They’d invited me down for dinner, but as usual, I’d told them that I was sick. I pressed my pillow to my head, thinking of why I wasn’t going down. I knew it wasn’t right to ignore them, but I felt anxious all over like spiders were under my skin. It felt like they had a lot of things to talk about, and they’d have less to talk about if I joined them and sat in the corner and ate my food.

Eventually, I left my room to pee. I always sit down when I urinate, because I am usually guilty of spreading pee all over the toilet seat. On the way back to my room, I passed Rosita’s bedroom. I glanced over at her closet, wondering if I’d hidden the cardboard box far enough in the back. I walked into the room, adamant to make sure that my plan went off without a hitch. When I opened the door, I noticed a white glint of something hanging from a coat hanger. I pushed back a jacket, and brushed away a couple of stray coat hangers. At first, I thought I was staring at a ghost. Then I realized it was a wedding gown, one of the same gowns that Rosita had spotted in the bridal shop that day.

I brought my fingers down the silk, feeling the softness. I fidgeted, for some reason more than I other had for weeks now. I realized Rosita was probably going to a wedding. It must have been a friend, I decided, or perhaps a member of her own family. But for some reason, my skin started to itch very badly. Then downstairs, I heard the sound of my father laughing. It shook me up quite a bit, and it made me sprint all the way back to my room. I swan-dived into my bed and pulled myself under the covers, fearful that a monster would be if I dangled my feet in the cold air. There was nothing to worry about, because this had to be another element of Rosita’s life. She was a nanny, and that was all, so why was I concerned about something that didn’t include me at all? But the more I thought about it, the more troubled I felt. There was nobody else I knew who was getting married, and yet Rosita had told me in the bridal shop that I was attending a woman. The only person she knew was my father, and if that was the case, why had she purchased a white gown for herself? The facts came to me very slowly, drifting like a river that slowly surged into blinding rapids. When I shut my eyes, and struggled to fall asleep, I tried not to picture my father walking Rosita down the aisle.

***

I sat on the porch the following morning, sipping a glass of diet Coca-Cola. I did this with trembling hands, because I still hadn’t quite recovered from my discovery the night before. We always buy the diet Coca-Cola, even though it rots your teeth and gives you cavities. I was sitting out in the backyard, thinking about Rosita and what the wedding dress could have entailed. I didn’t think she could be planning to marry anyone else, because she was from Ecuador and didn’t have any money. If she was intending to marry somebody she knew in her own country, this would have been impossible, because the groom would have been deported when he illegally crossed over the border. This made me very scared, because no matter how much I looked at different options, it all came back to one: Rosita was attempting to marry my father, and now I had to do something about it. There was the option of confronting him about it, and yet my father never listened to anything I said, and I wasn’t sure if I wanted to hear the truth either; to hear from his own lips that he’d lied to me, and had planned to be remarried so soon after the divorce. There had to be something I could do, but the question was what?

All of a sudden, I heard footsteps walking up my driveway. When I gazed up in the sunlight, I was taken aback to see Vanessa storming down the walkway. She was wearing a pink sweatshirt, and had her face tied up in a bun like she hadn’t slept very much. While she usually wore lots of makeup, her face was disheveled now, and looked like black tears had stained her face. She lived very far away in the bad side of town, and I wondered how she’d gotten all the way to our house unless she’d taken the bus.

“What do you want?” I asked coldly.

“Where’s your father?” Vanessa snapped. ”Is he at work?’

I nodded at her, but didn’t say anything.

She locked me in the eyes and said, “It turned blue. He’ll know what it means.”

“Blue?” I repeated. “What turned blue?”

“He’s been avoiding my phone messages. Tell him it turned blue. He’ll know what it means.”

“What turned blue?” I asked again.

But with that, she turned around and walked off, leaving me in the strange world that all adults do when they don’t explain what they are talking about. I thought of the ocean, and Smurfs and cotton-candy ice-cream, and all the things she could have been referring to. When I was finished, I still had a half-full glass of Coca-Cola, and no idea what would happen if my father ended up marrying Rosita.

***

Later that afternoon, Rosita sat in our kitchen and knitting something with a spool and yarn. She had asked me to accompany her, and I sat there trying to go through the difficult ritual of slipping a needle through a spool. It was very difficult, and it normally would have been enough to make me throw a tantrum. But for some reason, I was much calmer than usual, and it was only because I had so many things to think about. Rosita was much perkier than usual. She hummed Christian hymns and threaded the blue yarn over and over, stitching together something that looked like a mitten. In front of me, I only had tangled knots of yarn that looked like Chinese noodles, but none of that was very important. Several times, Rosita had smiled at me and tried to get me to smile back, but I wasn’t very interested at all.

“I have it all planned already,” she said, when I asked if there would be a wedding soon. “We’re going to have it at a hotel. A big, big wedding…”

I said, ‘But who are you marrying?’

“It’s a surprise,” Rosita said, smirking. “You’ll see. You can walk to the front of the aisle, and you can carry the ring.”

She chuckled and shushed her lips, urging me not to ask anything else. Then she walked out of the room. This made me angry, but more than anything, I blamed myself. Even when I was angry at her, I ended up in situations where she smiled at me, as if I’d done something to encourage it. I didn’t know whether this was because I was a kid, or because I was different and it’s just easier to smile at people who are like me.

When Rosita was gone, I glanced down at the dining room table, and I examined what Rosita had been knitting with the blue yarn. When I held it up to my eyes, glancing it over like a detective, I realized exactly what I was looking at. We had a few in the attic, but they hadn’t proven to be very useful since I’d grown up. In my hands, I held a pair of baby slippers.

***

“What do you mean it turned blue?”

“I just…I don’t—”

“What did she tell you?” my father yelled. “Where is she? What else did she say?”

“That’s…that’s all Vanessa said.”

We stood out in the parking lot of Friendly’s. Rosita had gone home for the weekend, and my Dad had taken me out to get ice cream as a special treat for my good behavior. Only a few minutes ago, I’d been fantasizing about a brown sundae, so much that I’d almost forgotten about the nightmare wedding lurking in the bowels of my imagination. When we reached the Friendly’s parking lot, I was reminded like an answering machine to tell my father about what I’d retained from Vanessa; it was the fact that something, for whatever reason, had turned blue. I had never seen an adult cry before. I had seen it in movies, but I had never seen it in real life. When I told this news to my father however, that was exactly what he did.

“Shit,” my father muttered, rubbing his eyes with his hands. “I’m finished. I’m completely finished.”

I watched my Dad paced around the parking lot, hands behind his head. It’s very strange and infuriating to cry, because they should be doing other things like paying your taxes. They should be going to work and driving you places, and it just isn’t a very nice thing to look at. It made me very anxious, and I backed into the car and started to whine. If I didn’t get information very soon, I was very soon I would kick the car and put a huge dent in it with my sneaker.

“What’s happening, Dad?” I demanded.

“It’s a mix-up…” he said finally. “But it’s all right. It’s fine….”

“How is it fine? What turned blue? Vanessa told me—”

“No. We’re not going to see Vanessa anymore, or Rosita,” he went on. “We’re going to go live with your relatives for a little bit, okay?”

I tried to protest, but he didn’t even let me say anything. He swung open the car door and shoved me inside, and it became very clear to me that we weren’t going to Friendly’s. I sat there, shriveled up, breathing into the upholstery. There was still that new car smell, but it seemed rancid for some reason and I could hardly breathe. Fumbling with the car keys, my father slid into the driver’s seat. I tried not to listen to him, and block him out completely, but he said the same thing over and over:

“We don’t deserve this. We don’t deserve this…”

“Dad,” I pleaded. There were tears in my eyes now, and I couldn’t help it. “We can’t leave Rosita.”

“It’s fine. I told you. It’s fine…”

“I want to say goodbye to Rosita—”

Then he put the keys in the ignition, revved the engine and drove off.

***

That night, we packed all of our bags. By the time we were finished, there were five duffel bags, and six backpacks sitting in the living room. My father decided to leave at five-thirty the next morning. I sat in my empty living room that night, huddled in a sleeping bag, watching the moon beam through the glass door that led to the porch. My father beside me was misshapen lump snoring. There’s a time of the night, I realized, where bad thoughts enter your head. It’s not that you’d commit any of them. It’s just that your mind fills in the gaps, and you wonder what you’re really capable of. I gripped one of the pillows on the floor. I imagined taking it and pressing the cotton to my father’s nose, sealing his mouth, blocking his nasal passage. There’d be a struggle, a gurgle for breath. Then I’d be out, under the moon and running free. Instead, in what seemed like the very opposite, I huddled closer to him and felt his scraggly beard.

I thought about where Rosita was sleeping right now, probably a one-bedroom apartment where she didn’t even own a can opener or a flat-screen television. I nudged closer to my Dad, so close that I could feel his hot breath. I would be whisked away by him, and accompany his wrongdoing for the rest of my life. We’d be like the devil in the Bible, beckoning people forward to perform nasty tricks on them. We’d made my mother disappear. We’d made Rosita lose her job, and Vanessa have something she cared about turn blue. I had thought Rosita was trying to marry my father, but clearly, I had been very wrong, and there was something going on that wasn’t my business. So at three forty-five in the morning, I stole my father’s cell phone and walked into the kitchen. The blue buttons glowed like ghosts, and I punched in a familiar number. I had decided to call Rosita, and I had to do it very quickly before my father woke up. I had decided to help Rosita and Vanessa, although I struggle to remember the details of the conversation that followed. It was because I was crying for most of it, and felt like I was floating in outer space. I do, however, have this equation that very well explains what I was thinking

***

We woke up very early to load our bags into the trunk. My Dad walked around the living room, mumbling, throwing things together into boxes. He packed up our electronics and our precious antiques, and he even dismantled the sprinkler system in our front yard. I sat on the porch and stared out at my front lawn, counting as many blades of grass as I could. I do that when I’m anxious, even though the numbers never add up, and I never get past five-thousand. By five forty-five, I watched as my father packed the last duffel bag into the car. I sat there alone on the porch, a wrapped cardboard box beside me.

“What’s that?” my father asked, staring at the box.

“A present…” I said simply.

“Well, come on. We don’t have time. We have to get out of here.”

I stared at the car, but I didn’t follow. I sat there in my windbreaker, pulling at the strings. The breeze whipped at my cheeks. I felt a harsh burning in my face, even if there was nothing touching it. Words were surging inside, stilted and broken and longing to be set free.

“Get in the car, c’mon.”

“No.”

“What do you mean “no?”

“I….I have your keys, Dad,” I said quietly.

I fished into my pocket and pulled them out. I had taken them only moments before, when my father had left them on the hood of his Porsche. I raised them in the air, displaying them like an auctioneer. My father’s golden car key, the key to his Porsche, was jingling on the ring next to his platinum gym membership. There were seven keys, four cards and one miniature keychain of my second-grade yearbook picture. I squeezed them all in my palm, and then clenched my fist so hard it felt like I was going to blend. I took a deep breath, and then I picked up the wrapped box at my side. With that, I took off. I hurried back to the house and swung it open, and shut the door behind me. There was a flurry of movement as my father unbuckled his seatbelt outside and climbing up the porch. When he came up, I’d already locked the door.

“Son…”

He stared at me through the screen. I just shook my head, unable to look at him. I just hugged the box and waited for it to be over.

“I’m not going with you…” I stammered.

“What?”

“The house,” I said. My fingers were itching to touch my face, to rip at it until I was nothing but a dripping skeleton. “If we don’t need the house anymore, we should give it to Rosita and Vanessa. They don’t have a house, and so that’s why we should give it.”

“That doesn’t make any sense!” my father said.

“No!” I replied. “They only have an apartment, and that’s bad!”

I turned and ignored him as he struggled to open the door. I hummed Christian hymns to myself, covering my ears as my father tugged at the door. He dug his fingers into the screen, trying to rip it off but having difficulty. This lasted a good time, and by the time he was finished I’d kicked four dents in the hallway wall with my sneakers. I’d wailed a lot, and this seemed to tire out my father as much as it tired out me. Finally, he gave up and stared out at our yard that stretched off into an identical stretch of white homes and picket fences.

“Unbelievable…” he muttered to himself.

***

Five minutes passed.

Now, my father was facing the other direction. On any other day, this was the time where we’d drive down the street to look for the grass people to hire for work. Now, he was disheveled and dressed in a raggedy sweatshirt, and his face was chiseled by five-o-clock shadow. Every so often, I’d see him in the corner of my eyes, and I’d shudder and turn away to face the wall. I had started to look at the tiny dots left behind by the paint, and developed a graph in my head to figure out if there were more of these dots on the top of the wall or near the bottom.

“Come on, what do you want?’ my father asked. ‘Do you want to go to robotics camp? I’ll pay for it. What do you want? Just tell me.”

I didn’t say anything, and Rosita arrived ten minutes later.

***

She walked out of the haze, stomping down the driveway in a purple windbreaker. Her brown hair, knotted and frayed, hung out of the hood like wild whips. As she approached, she zeroed in on my father standing by the front door. My father turned around and saw her, and didn’t waste a second before he made a break for the car. While I felt an urge to run with him, I could only stand back and watch, hugging the cardboard box like a life preserver. By the time my father reached the car, Rosita had gotten there first and stood in front of the driver’s door. My father reached out his hand, but it became locked in mid-air like she controlled it with her mind. He was like one of those criminals who knew they were about to be arrested on television, and who could only cower on the ground as the cops asked them to raise their arms.

“It was an accident,” my father mumbled to Rosita. “There was never anything I could have done.”

“You say that now,” Rosita said sharply. “You shouldn’t have been in the first place, if you were just going to run out on her.”

“There was never anything between us,” my father said simply. “And I…I don’t think I should be liable for the baby…”

I parted the screen, trying to glance at Rosita’s face, but it was lost in the early morning shadows. My fingers fidgeted, picking at the tape of the cardboard box in my hands. I thought I’d heard baby, but I wasn’t entirely sure, because I wasn’t sure what role a baby had in any of this.

“Well, was it genuine on her part?” my father snapped. He seemed to be struggling to stay calm, as if this was a normal conversation he had on Wall Street. “Or did you just want citizenship? That’s what I’d like to know.”

“She was happy with you—” Rosita said. “I swear, she was happy with you, and I just want you to know—”

“But after all this, I’m starting to question if she was – if she was genuine – or if you were putting her up to this—”

“She doesn’t talk to me,” Rosita shot back. “How am I supposed to know?”

“Well, what do you want? I’ll pay for it. How do you want to do it?”

“It’s not an it,” Rosita said, and at that point, it sounded like she was crying. “It’s her baby.”

I unlocked the front door. I walked down the front steps. I hurried over with the cardboard box in my arms. Rosita’s eyes were bleary, yellowed and wet from not sleeping. When I looked at her now, it was like I was wearing three-dimensional glasses, because she looked very real. Next to the trees and the driveway, she popped out more than anything else, and it was like she was a living movie poster.

“Rosita…” I stammered. “You can have my house, but you can’t marry my father…”

‘Wait – what is this?” my father asked, eyes locked on the cardboard box in my hands.

He grabbed the box. I tried to snatch it back, but he ripped off the wrapping. He tore through all my Christmas paper, all seven years worth of it, which included the snowmen and the reindeer and the one with Santa sliding down the chimney. There, buried in the depths, he found my assembly of gifts that I’d stolen from around our house

“What is this?’ my father asked, pulling out the remote with widened eyes.

I didn’t know what was about to happen, but I knew it wasn’t anything good. I had stolen the gifts after all, and they had absolutely nothing to do with Rosita. It was my house, and that meant it was my property as well, and that I was free to do whatever I wanted with it. My mother, after all, had taken half of our possessions with her when we’d divorced. I yelped and tugged at my father’s jeans. I writhed my arms, shaking my legs to try to bring him down to the driveway. My father pulled me, binding me at his side like a frightened animal.

“Rosita,” my father said. “Were you stealing from us?”

“She wasn’t,” I said. “Tell him, Rosita…”

But for some reason, Rosita nothing and only stared at him. I didn’t understand, because I’d never seen somebody accept a lie when somebody else lied for them. She eyed us carefully, almost like we had caught her in a game of hide-and-seek and were trying to get her to come out of hiding.

“Rosita,” my father said. “If you confess, we won’t have to call the authorities.”

“Yes,” she said finally. It was a lie, and she knew it and I knew it too. “I did…”

“So we’ll settle this now. I’ll pay for Vanessa. I’ll get rid of it. The baby. But you have to leave….”

We stood there in the cold. The dark had left. The birds were chirping. Rosita looked to my father, and then to the house, and maybe saw something that we didn’t. Like a slit that wouldn’t quite shut, her mouth never closed. I had always been troubled by how people’s faces looked, because their faces could mean thousands of different things. Right now, Rosita looked a bit like a tea kettle that was blowing, and her eyes were wedged up tight together. There was no announcement or fireworks or final inducement to announce the removal of my nanny. Without looking at me, Rosita pulled up the hood of her windbreaker. Then she walked away like some kind of animal burrowing up to hide.

“It’s fine…,” my father said simply, hugging me at my side. “We were trying to help.”

***

It was six-thirty on Main Street. The morning was skylight purple, a stream of yellow perched just over the buildings. Up and down the street, landscapers were sitting out with their rakes and hoses and garbage bags full of tools. One of them washed somebody’s Sedan, wiping the dashboard down with a wet rag. A group of three spoke to a man in a Ford Explorer, willing to cement his patio for fifteen dollars an hour. Sitting in a Porsche, a boy and his father were parked near the diner.

“We’re going to need about seven,” the father said, watching the migrants pass. “Maybe eight.”

“I used to stand right over there,” the father said, shooting for a smile. “I’d stand right by the fishery until someone came to ask for work…”

“Well, are you ready to go?” the boy asked.

A young Hispanic woman was walking across the street with a toddler. The woman glanced at the Porsche and nodded. The father waved back, but the son didn’t.

“Are you ready to go?” the father asked, sending the question back.

The father unbuckled his seatbelt and got out of the car. He looked back through the window, smiling back at him.

“Y’know, you’re slowing me down here…” he said. “Come on, hustle and bustle…”

The boy shrugged. “I’m tired …

His father chuckled. “C’mon, can’t you put other people first for once?”

“What do you mean?”

“You’d think I’m going to hell or something…” he said.

“No,” the son said finally. “If you went to hell, I’d come with you…”

The son got out. He headed down the sidewalk, his father walking beside him. After a moment, he slung his arms around his son’s shoulder. The boy grimaced for a moment, startled…and then allowed it. Up and down the street, the landscapers walked the slow, slow rhythm of the day ahead.