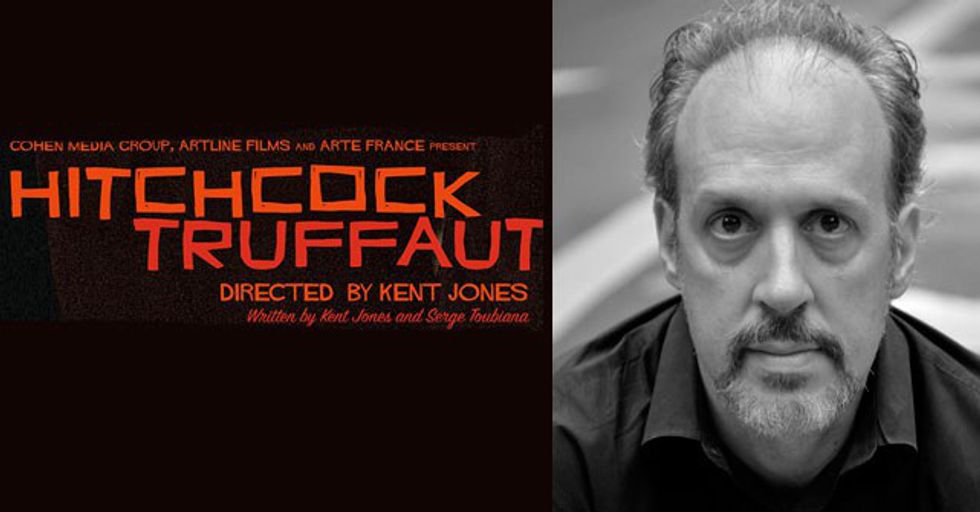

Kent Jones attempts to re-solidify Alfred Hitchcock’s reputation and accentuate his importance within cinema’s history. Jones revisited the historical interviews between Francois Truffaut and Hitchcock that resulted in the creation of Truffaut’s book "Hitchcock/Truffaut" more commonly known as "Hitchcock." In his documentary, Jones interviews a cast of world-renowned filmmakers who analyze and pose their opinions on Truffaut’s insights and Hitchcockian themes, elements and techniques selected from Hitchcock's oeuvre. In this documentary, Jones opens his audience's perspective to a new understanding of Hitchcock’s innovations through the intercommunication of filmmakers.

It is with this medium that Jones is able to gather insight from these renowned filmmakers of today such as Wes Anderson, David Fincher, Olivier Assayas, Richard Linklater, James Gray and Martin Scorsese. The focus of these interviews is arguably one of the most notable and revolutionary alterations to a filmmaker's reputation in cinematic history. Before Truffaut’s interviews and the publication of his book, Alfred Hitchcock was revered as a “light entertainer” within American and British film criticisms. Truffaut perceived Hitchcock’s works at a profoundly deeper level than the majority of critics during his time.

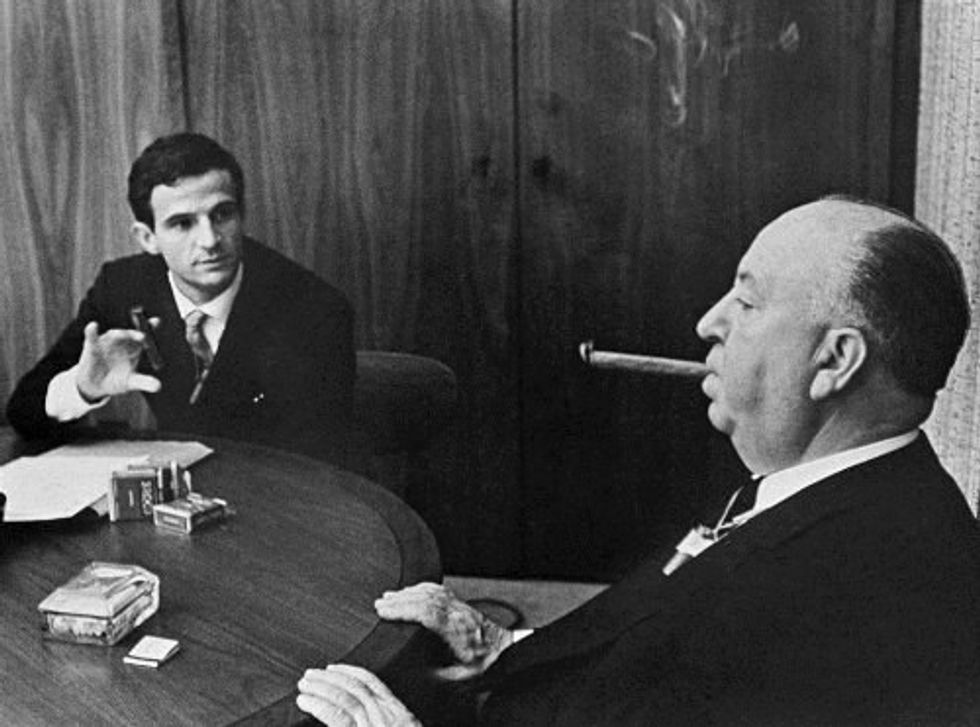

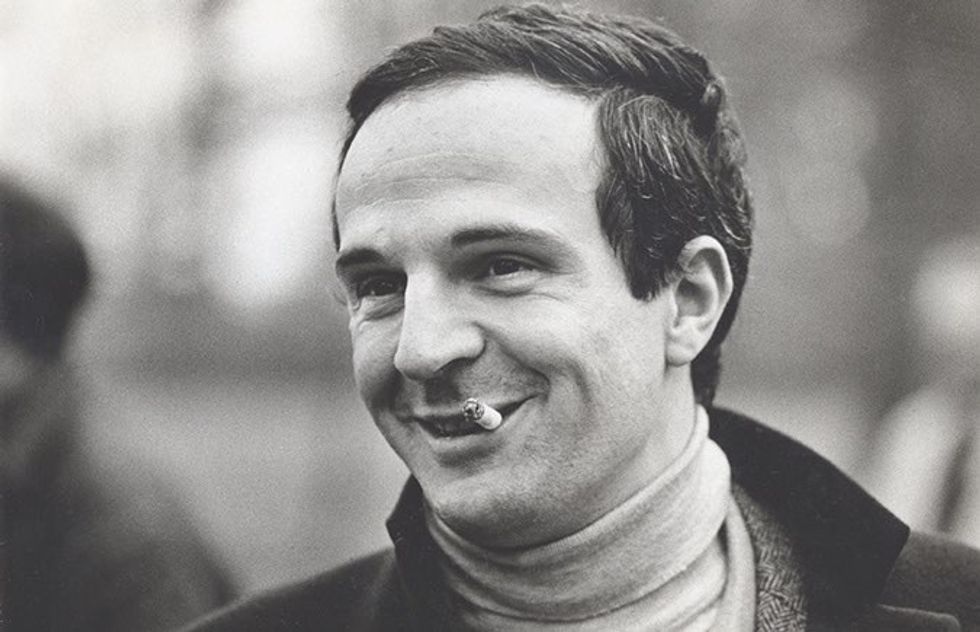

He sought to free Hitchcock from his "mis-reputation" and transform it into that of a "legend of cinema." The young and eager Frenchman utilized the process of interviewing the artist himself, not only to sit in a room for eight days with Alfred Hitchcock, but it allowed him ample time along with the access necessary to focus on the numerous innovative qualities of Hitchcock that are forever mirrored in his works.

Jones completely misses the head on the nail when the narrative reaches the alteration of Hitchcock's reputation. There is an absence of insight in the story. The narrative solely maintains a light and appealing observance and glorification of Hitchcock's oeuvre. Periodically the filmmakers will subtly reveal technical terminology along with their application within the select Hitchcock film, but without any supporting counterexamples. At this point, the audience is being forced to accept everything as fact or fiction. Additionally, the documentary swiftly glances over very important aspects such as Hitchcock's background, Truffaut’s rise to fame in the French film era of the ‘new wave’, and the auteur theory.

On multiple accounts, the film conveys that Truffaut’s book ‘did’ alter and solidify Hitchcock’s reputation in cinema, but it doesn’t explain how it influenced and converted an entire culture's opinion of a single filmmaker. It’s as if Jones forgot about Truffaut and his book altogether or the audience is to assume he was merely using them as bait in order to assemble his analytical team of filmmakers. This documentary becomes a series of analyses set by the filmmakers who only leave their appreciation of Hitchcock's works for the audience to mindlessly consume.

It’s not until later when the filmmakers begin to analyze key moments in Hitchcock's filmography that Jones shows the audience the difference between interpretation and intention. At this stage in the film the viewer is able to understand Jones's methodology beginning with “critical reception, then a reevaluation from the aforementioned filmmakers, and finally how, and why, Hitchcock shot a sequence in a particular fashion.” when discussing the birds eye view shot of the explosion in Hitchcock's film The Birds, his cast of filmmakers describe the use of this technique as “transcendental,” “apocalyptic” and “religious”. All three opinions can be valid, as can any personal perspective. Hitchcock, on the other hand, considered the shot practical because everything can be seen in it. Meaning, he created it simply because it felt right to him through a sense of practicality

The documentary loses a portion of its historical and logical aspects; however, it still undeniably contains qualified key insights from exceptionally distinguished filmmakers. For instance, David Fincher reiterates Truffaut’s insight of Hitchcock's oeuvre, that he has not forgotten the “lost secret” of silent films. Hitchcock meticulously designed his films with the ability to virtually narrate his stories solely through its visual aspect. Today, a film without sound would noticeably be missing an integral element within the medium of storytelling, but if all elements are utilized accordingly a narrative is more than capable to be perceived similarly even with the absence of its sound. Additionally, Richard Linklater critically insights the issue of control that Hitchcock has in many of his films, especially his later ones. Linklater argues that it restricts his actors abilities, instead of allowing them to be more spontaneous and improvise, which can give a film a new element of freedom. Hitchcock tries to mold his characters exactly as he imagined them leaving no room for error in his eyes. Martin Scorsese advocates that Hitchcock's film "Psycho" indicated what lay ahead in the 1960’s. Scorsese is recognizing the reach of Hitchcock's visions and his influence on film of the time based upon one of his most thrilling works and the history of film which followed it. The documentary is then compelled into a more alien, in depth, and elongated portion over Hitchcock's inability to suppress his preoccupations which vividly surface throughout his works.

For example, in "Vertigo," Hitchcock's obsession with Kim Novak's character’s transformation is overbearingly grim and quite uncomfortable for the viewer. Take his grim obsession and correlate it to a statement made by David Fincher, “If you think you can hide your prurient interest as a director, you’re crazy.” He believes it is impossible for Hitchcock to suppress all or any of his preoccupations from surfacing within his films as a director. Finally, an insight provided by James Gray and Olivier Assayas, encompass Alfred Hitchcock’s films on multiple levels. Levels of white-knuckled entertainment; marvels of composition, light and space; personal preoccupations and poetic expressions of certain universal human anxieties. They believe that every Hitchcock film is gripping, technically fluid and portrays a sense of himself within a mixture of relatable anxieties that everyone shares. A scene from the documentary shows a portion of one of the original interviews to where Truffaut interjects an aspect from one of his own films “The 400 Blows” while discussing the idea of “suspense or surprise” with Hitchcock.

This scene is notable due to the fact that the roles of who is being interviewed immediately switch casually in one fluid motion. Resulting in the question of ‘do filmmakers interviewing filmmakers have an advantage over critics interviewing filmmakers’. People who share similar knowledge, interest and reputations will always be able to discuss specific topics in depth easier than that of a more imbalanced pairing. It is because of this fact that the original interviews were able to show the true Hitchcock and forever alter his reputation and similarly how the documentary is able to reach certain depths in reviving the same idea, even if it avoids going in depth at moments.

Kent Jones and Francois Truffaut shared comparable goals and through their own means attempted to fulfil them. Even though Jones doesn’t maintain the same recognition as Truffaut does today, he still succeeded by reincorporating as well as continuing the necessary expansion of education upon the documentation and story of a cinematic legend. The fact that Hitchcock did not hold a well established reputation in western cultures didn’t mean every facet of his psychoanalytic narratives were any different than before. The narrative of Alfred Hitchcock is now integrated into the same beloved medium as his own works.