To be honest, even at the time of me writing this review, I'm not quite sure how I feel about Freetown Sound aurally, the third album from Blood Orange (the moniker under which producer, composer, singer-songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist Dev Hynes has created his solo music for the past five years).

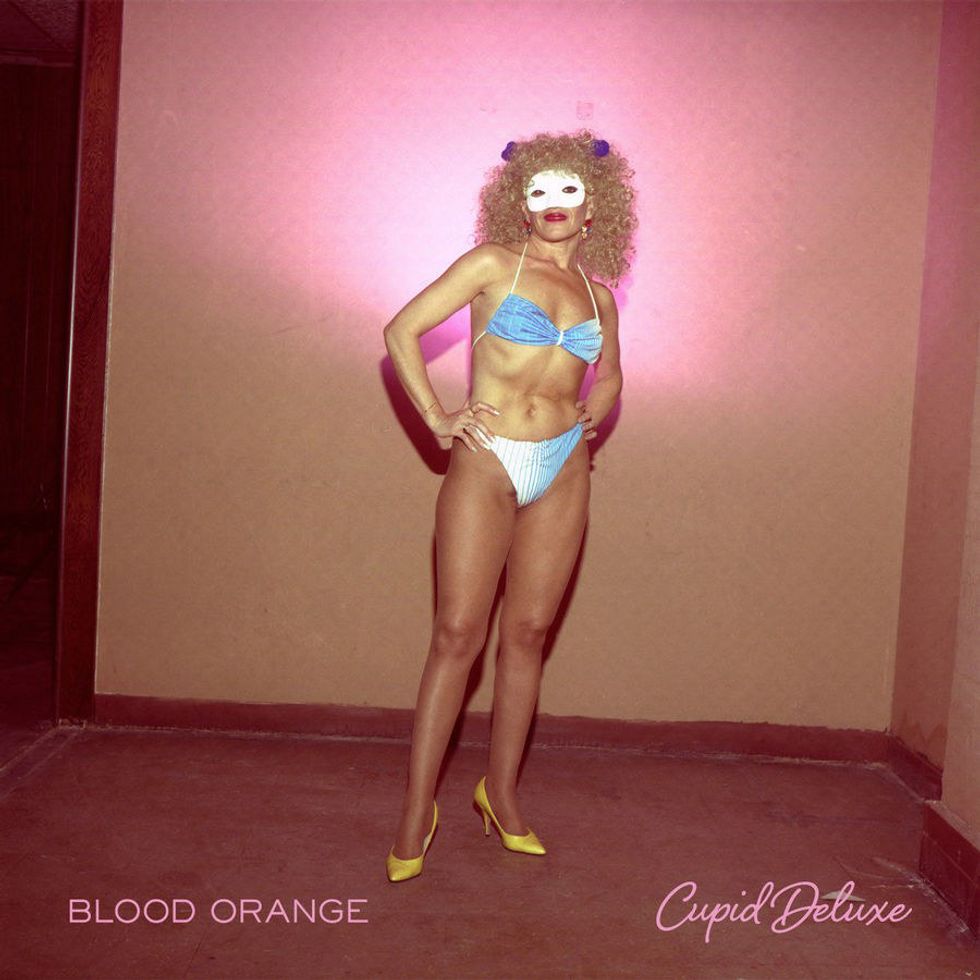

I've listened to this album six or seven times now, and every time I listened I have a completely different reaction. At first, I flat out hated it, I thought it was a Michael Jackson rip-off that was drowned in reverb and was rhythmically off. Interestingly enough, Blood Orange's second album Cupid Deluxe elicited a similar response from me at first. I thought it was sappy, too caught up in sounding like bad '80s music, and just generally not my scene.

The first time I saw him live at FYF in Los Angeles two years ago I was still unsure of how I felt--my best friend loved him and cited the show as her favorite of the festival, but I was underwhelmed and bored. (Funny enough, there was an audience member in front of me who was texting his friend my exact reaction: Why are people into this? I'm just here for the next act so I get a good spot.) But when I got home from that festival, my friend's sublime reaction led me to listen to the album itself some more, and now, two years later, it's one of my favorite albums of the past decade; I adore it. It was the soundtrack that got me through a rough patch in my sophomore year of college, as I found the mellow and subdued introspection worked well for me when sorting through deep questions in my own life. I liked the nostalgic vibes only in that he found ways to transform them into something contemporary and emotionally impactful. I found myself a true Blood Orange fan, going back to listen to his first album, Coastal Grooves, which was less synth pop and more indie rock with a synth pop edge, and eagerly awaited his follow-up to Cupid Deluxe.

But my love for him was really solidified by the work he did as a producer and writer during the interim between albums; he made me want to listen to Carly Rae Jepsen, which is a feat in itself, he helped propel Solange's music to new heights, infusing his unique take on contemporary black identity in some of the lyrics and in the music videos.

I follow him on Instagram and am constantly impressed by what he is posting, both musically and visually--he is a clear fighter for racial justice, both in his actual presence at rallies and events and in his ability to imbue his art with political messages. His cultural literacy and thus his cultural relevance is almost insurmountable. He is the celebrity we need who's work is inextricably tied to his experience, even the political and social components of it. The work that he teased leading up to this third release made me hopeful for what was to come. His highly important and beautiful song, "Sandra's Smile," for Sandra Bland one of the many black individuals killed at the hands of police, was accompanied by a music video with a number of important black cultural influencers. And the first single from Freetown Sound, "Hadron Collider," was slightly less musically upbeat than I would have liked but seemed like an indicator that there was much goodness to be found on the impending album.

And since listening to the tracks a number of times, I've found much of that good, but it is not as consistent on the album as I would have liked. When I truly think about why I was so conflicted on whether or not I liked it, it is due to the fact that the lack of consistency is not just across the album but within individual songs. So while there are some songs that I like and some that I don't there are also a ton of tracks that I only like snippets of. "Best of You" is the clearest example of this for me, as the musicality of it sounds a lot like one of my favorite bands, Bombay Bicycle Club, but the vocals sound like they should be in some popular EDM track.

For another instance, the only single with a music video so far, "Augustine," is a great song, but the chorus becomes a bit too saccharine sweet for my taste. In fact, the overall shiny gloss that the whole album has been given takes away from some of the unfinished components that gave the previous album its more self-aware vibe. In other words, this album comes off far more like a pop album than his previous endeavors, which would help explain why I felt more like I was listening to an MJ album than an indie Blood Orange one. This mixing also, in my opinion, hurts many of the featured singers on the tracks, which include punk goddess Debbie Harry, pop star Nelly Furtado, the aforementioned Carly Rae Jepsen, and Zuri Marley. Instead of hearing each of their distinct voices, the reverb just blows them all out, neutralizing any unique characteristics of their sound. I was actually unaware of the most of the featured artists until I looked up the production notes.

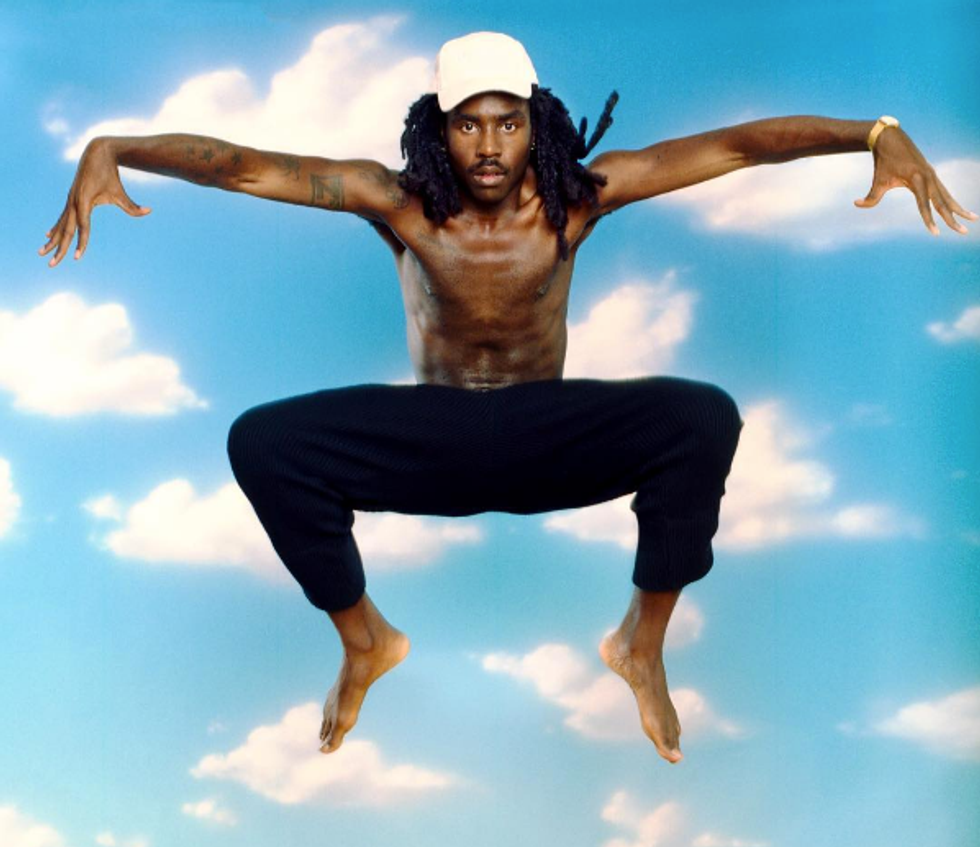

What saves this album from its heavy-handed pop mentality is the questioning of identity politics and larger political dialogues he embeds throughout. Freetown, the city mentioned in the album title, is the capital of the African country Sierra Leone, the city in which his father was born. He notes his African heritage at numerous points in the songs, tying himself to a distinct part of his identity. But he averts stereotype by inserting new conceptions of black identity outside of the continent of Africa, as well. In his Instagram post announcing the album's release he noted that the album is for anyone who had been told they were "not black enough, too black, too queer, not queer in the right way." Rather than present only an antiquated idea of blackness and its ties to the continent of Africa, he complicates the black identity, allowing for a black male to outwardly express queerness with his dance training and skills, specifically in regards to his ballet and vogueing influence (a dance form historically crafted by queer minorities). His entire existence as an indie rock and indie pop musician, dancer, and author validates black identities that do not fit the racial narrative of America, showing the uniqueness of identifications that have emerged as African immigrants spread across the globe and their descendants have grown up between cultures, not fully accepted by their native Western nations or the continent from which they descended. "Augustine" calls to this in references both to his heritage and the Western issues that black individuals now face, ending the song in a repeated Zulu verse. And even the album art is reflective of this message (like his previous two records, too)--the photo taken is very similar to artworks created by post-black artist Mickalene Thomas, a queer black photographer and painter who attempts to complicate black identity with her vibrant '70s style imagery of queer women. This cover seems to be doing this with a modern flare, a la another queer black painter, Kehinde Wiley.

With this said, I believe that "By Ourselves," the first track on the album, is my favorite. The latter half of the song a poem performed by the black poet Ashlee Haze regarding the specific brand of feminism that black women must craft to counter the plight of white feminists on black bodies. The song "Chance" discusses some of the white culture which Hynes associated himself with in his youth and the tensions it presents when considering his African heritage and the white-washing that has removed it from common-told histories. "With Him," essentially presents itself as a poem on what blackness is, delving into soul- and blues-style vocals. "E.V.P" talks specifically about the change of lifestyle one feels as an immigrant (Hynes emigrated to the United States from Britain in 2007) and the lack of contentment possible in such a situation. "Love Ya," one of my other favorite tracks on the album musically, ends with a sample of writing by Ta-Nehisi Coates discussing the way black men must think about the ways in which they present themselves visually to a white world, even at a young age. The song "But You," could easily be an early version of the King of Pop's "We Are the World" with a chorus line of "You are special in your own way." While this pop sweetness is a little overdone, the message is clear and necessary, validating the many intersecting identities with which black individuals now associate. "Hands Up" is one of the most overtly political songs on the album, with the title referring to the police brutality that an insurmountable number of black families have had to face, with increasing documentation and unchanging levels of conviction. The entire song details the actions that black men, specifically, must take in order to avoid being the next hashtag on social media; there are direct references to Trayvon Martin and the hood he had up at the time of his shooting. The song ends with the words "Don't shoot" repeated. "Hadron Collider" seems to function as a metaphor for how far the black community has left to go before true equality and justice. The last third of the album takes on an overtly religious tone, beginning with "Juicy 1-4" which is also quite direct in its language of racial injustice; it is structured as a prayer asking what can still be done in such a dismal reality. "Better Than Me" seems to relay the inadequacy that he sometimes feels as a black man in society, and the music actually quite rightly fits the lyrics, with a disjointed feeling. "Thank You" is a clear giving of thanks to God, ending in a sample describing the inequality of the black population: "A meteor has more rights than my people."

So in short, I conceptually love this album. It is significantly important in our current political and cultural climate, especially after the shooting deaths of two black men, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, and five Dallas police officers this past week. The Civil Rights Movement never truly ended and racial equality has never been realized. We are in a defining moment in this country, our black brothers and sisters have been brutalized in our inability to see them as fully formed three-dimensional human beings, but as an Other too unlike ourselves. All of this has been rooted in stereotype, and we must work to meet and understand our fellow citizens in their whole human capacity, their entirety. As the too-oft used adage (one that was plastered around my Catholic high school) goes, you can't hate the one whose story you know. Learn these stories and their complexity, humanize those who have never deserved less. Blood Orange takes this stance firmly, and it is such an important message to hear in contemporary media sources. It's worth a listen even if to just hear this story told in a unique way. But it isn't perfect, from a musical standpoint I wish the sound had matched message if only to make it more impactful.