"A cynical bisexual atheist accidentally joins an evangelical Christian group full of liberal hippies and learns the true meaning of community." Sounds like a sitcom pitch, doesn’t it? Or maybe the jacket copy for a schmaltzy memoir you'd find at Barnes and Noble, somewhere between Bossypants and Heaven Is For Real. It’s neither of those things (yet), but it is what happened to me in college.

Or, at least, it’s the story I used to tell myself about what happened to me in college. See, the evangelical group in question is InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, which made headlines last fall for firing staff who supported same-sex marriage. That’s when this seemingly perfect character arc I’d had in college, from aspiring Vulcan to person-with-actual-friends, started to unravel before my eyes, and all I could think was this:

But they were so good to me. They were so good to me.

I realized I was an atheist one Sunday morning when I was four. All us elementary-age kids were gathered in a big room for Sunday School, and the adults were talking about how God was everywhere, and tiny me said four words: "I don't see him."

Was I missing the point? Almost certainly. Did anyone try to set me straight? To be honest, I don't think anyone heard me. But regardless, that was when it clicked in my brain -- you know, this religion thing isn't going to work for me. And that was that... except I still had to go to church every Sunday, because that was just what my family did. We got up at 7 AM, I grudgingly dressed in something other than a T-shirt, I wailed as first my mother and then my father pulled at the knots in my hair, and we went to the early service at the Lutheran church a couple miles from our house. For years, I slouched in the pew next to my parents and younger sister. I drew flowers. I grew thorns.

Things got worse in eighth grade, with the pressure of Confirmation (AKA Affirmation of Baptism), and more generally my irritation at having to pay lip service to Christianity. I walked up to the altar with the rest of my classmates on Confirmation day and told the biggest lie of my life: the pastor asked if I’d be faithful to the church and spread the word of God or whatever, and I was supposed to say, “I do, and I ask God to help me.” My voice was deceptively strong, and my smile was convincing in every single picture my intensely religious relatives took. I almost felt betrayed -- was I that good at faking it?

I never wanted to set foot in a church again if it meant being fake like that. Eventually, when ninth grade came along and I went to public school for the first time (I had been homeschooled up till that point), I stopped going. It was such a relief.

About four years later, I walked into my freshman dorm at the University of Oklahoma, my brand-new home away from home, to see that although my potluck roommate with whom I’d exchanged maybe two emails was nowhere to be seen, she had already moved her stuff in. Her bed was all done up, a few handmade paintings were Command-stripped to the wall, and the bookshelf above her desk was full. It looked like a microcosm of Mardel’s.

I had a full-on cinematic flashback to my mother’s tales of her fundamentalist college roommate. What if I walked in on her while she was praying, like my mother did repeatedly (albeit accidentally)? What if she tried to convert me? I had spent my entire life in Oklahoma, so I was prepared for persistent questioning and overt proselytizing.

I wasn’t prepared for friends.

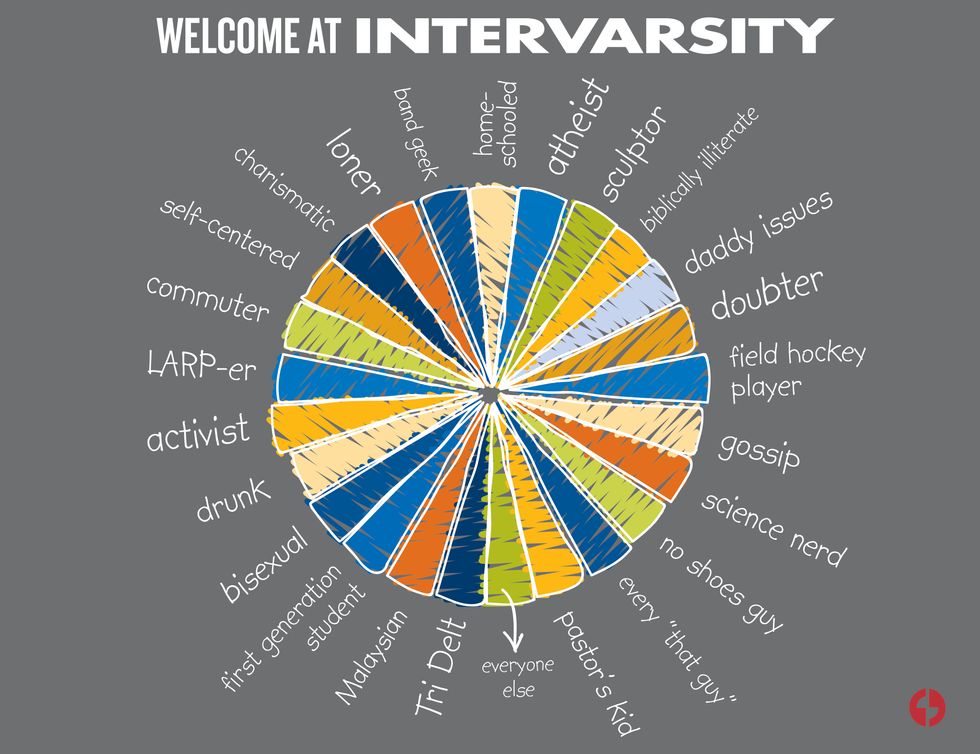

Soon before school started, I met some members of OU’s InterVarsity chapter for the first time, all of them sweet, genuine people. Thanks to a mass text my roommate would send out nearly every evening, I ended up regularly eating dinner in the school cafeteria with these same people, and more besides. I told my roommate I was an atheist pretty early on, when she asked if I wanted to go to church with her, and she neither shunned me nor actively tried to convert me. She did, however, make sure I knew I was welcome to come to a large group Bible study any time, an invitation I finally (if hesitantly) accepted halfway into fall semester. Some faces were familiar from cafeteria confabs, but even people who didn’t know me were so excited to meet me. It was a little disarming, but I liked it -- until, that is, the head staff worker mentioned that we would divide into smaller groups and read the night’s Bible passage aloud. My heart leapt into my throat, and my old church-related fears came roaring back in an instant.

Despite that, though, my voice was strong when I read my allocated three sentences, just as it was during Confirmation. Even after four-and-some years, I was a good faker.

I only went to a few large groups over the next couple years, though I routinely hung out with IV people at dinner and during Friday afternoon teatime (yes, that was and is a thing). The people were what kept me coming. Every time I showed up at large group, everybody was thrilled to see me. They always asked how I’d been, and they all gave fantastic hugs. In spite of that, though, in spite of the fact that InterVarsity people were 80 percent of my friends, I refused to count myself as part of InterVarsity. My enduring emotional baggage regarding religion was one part of it, but there was another part: I’d realized I was bisexual. Even before the staff purge of 2016, IV’s record with queer people wasn’t exactly encouraging. A chapter at SUNY Buffalo came under fire when its openly gay treasurer resigned due to doctrinal disputes, for example. (How I missed the InterVarsity Press book Love is an Orientation by Andrew Marin during my Googling, I’m not entirely sure.) So for a while, I stayed at arm’s length. I almost didn’t want to know whether or not I’d be truly accepted. It was almost better not to know.

For a while. I finally bit the bullet spring semester of my sophomore year and asked -- and I received reassurance from someone high up in the group (I don’t want to name names) that my bisexual atheist self would still absolutely be welcome.

I didn’t burst out of the closet after that, only coming out to one or two close IV friends. I spent the next year and a half inching my way out of the closet, quietly reveling in the fact that I wasn’t being my own Big Brother for a change. There were still awkward moments here and there, make no mistake, most notably the small group Bible study in which I had to pray aloud for the first time ever (it went something like this: “Hey, uh… God… what’s up?”). But my junior year, I started going to large group Bible studies every week. I told myself it was to supplement a class I was taking, on the Bible as literature, but really I just wanted to spend more time around these people. I felt safe around them. I felt loved around them. Over the next couple years, I came out of my shell, and my friends (friends) still liked me. I went to a church service for the first time in about six years during my senior year; at one point, my roommate, to whom I’d recently come out, prayed the most encouraging, validating prayer over me and almost brought me to tears. I made some truly irreverent jokes during Bible studies, including drawing a cartoon of Kronk from The Emperor’s New Groove in order to poke fun at a particularly repetitive NIV passage, and they laughed. I was so happy and so at peace with myself by the time I graduated from OU. All my old religious baggage was gone. I readily talked about my great experience in IV, often joking that although they didn’t convert me into a Christian, they converted me into a hugging person. I’d had the perfect little bildungsroman character arc, worthy of an indie movie or an uplifting longform essay.

And I had no idea how I could possibly follow that up, because not too many stories tell you what happens after happily ever after.

After, for a time, was a lot of aimless, anxious drifting. I spent a restless year living at home and working full-time, trying to figure out how to define myself now that my name, my year, and my major weren’t a guaranteed conversation starter. I moved to Canada for grad school, eventually. And then news of the InterVarsity purge broke. I signed the alumni petition against the purge, adding an emotional note to it and coming out on Facebook in the process. I talked about my InterVarsity experience on Twitter, trying to wrap my head around how this organization that had been so good to me -- so good for me -- could possibly take such a backwards step. Little by little, holes in my own story occurred to me. I couldn’t, can’t, reveal the name of the IV person who told me I’d be welcome in the group, my sophomore year. I was never out to the whole group, just to a few people. I don’t think I ever actually admitted I was an atheist to more than a few people, either. Would the story have been different if I’d been more honest?

I don’t know for sure. But after finding out just how many evangelicals voted for Donald Trump, I’m inclined to think it wouldn’t have been too pretty.

Ever since October, I’ve been wrestling with all this, trying to figure out if my cherished college memories are -- or should be -- tainted beyond repair. I haven’t come to any earth-shattering realizations just yet, so I don’t think I can wrap up this essay very neatly. I don’t think that’s the point, either. One of the things I liked most about IV was that large and small groups alike felt more like English classes than church. People actually asked questions about the Bible. They explored the cultural context surrounding Christianity. They interrogated their own belief system. That was perhaps the most important thing I learned from these people, that you can and should always ask questions, especially about yourself and your history and your beliefs. I may not know how the hell to deal with this brand-new religious baggage I have, but there’s one thing I know I can do: ask myself the hard questions, and not be afraid of the answers.