There are many great figures in the American anti-slavery movement. Most notable abolitionists, people like Harriet Tubman and Nat Turner, were once themselves slaves. Few white men ever shed blood for the freedom of black people. John Brown was one of those few.

Born on May 9, 1800, John Brown became of a part of the abolitionist movement at age 46 after moving to the progressive city of Springfield, Massachusetts. He became a parishioner of the Sanford Street Free Church, an important stop on the Underground Railroad and a major platform for abolitionist voices. Here he heard the stirring words of abolitionists like Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass.

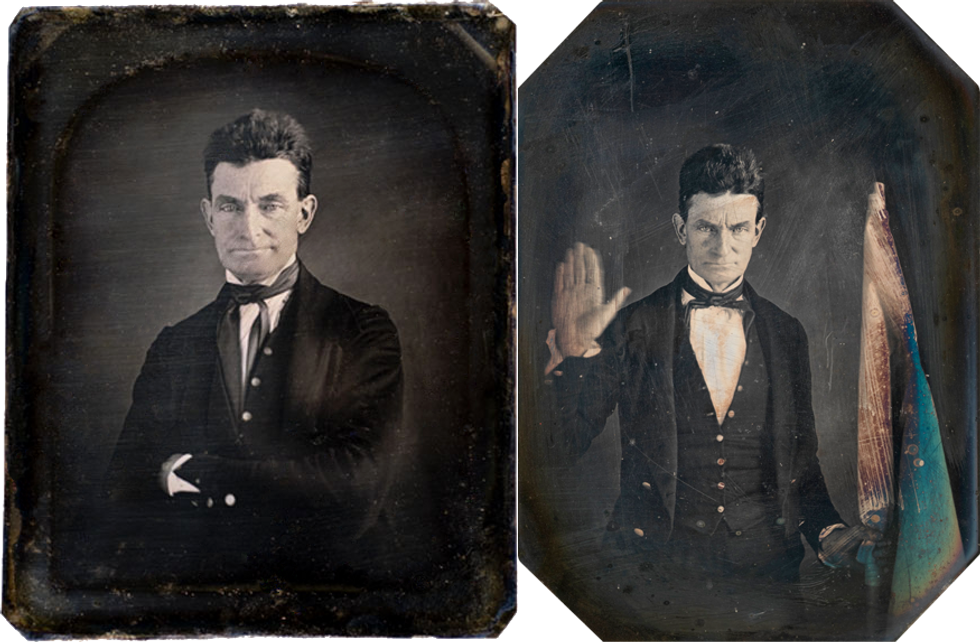

Daguerreotypes of Brown, one with the flag of the Underground Railroad, taken by black photographer Augustus Washington. | Photo: Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

After an 1847 lecture, Douglass and Brown spent an evening together which Douglass claimed changed his entire outlook on the abolitionist movement. He remarked that, "From this night spent with John Brown ... while I continued to write and speak against slavery, I became all the same less hopeful for its peaceful abolition. My utterances became more and more tinged by the color of this man’s strong impressions."

John Brown was a militant. Having been schooled in Christian Perfectionism, he had zero tolerance for the evils of slavery. Unlike most white abolitionists, he had no hope for a peaceful end to slavery and he welcomed no compromise.

"I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood."

His heart ached not only for the plight of black slaves but also for women and Native Americans. He was a proud feminist who made sure his sons did housework alongside his daughters (housework was something which men were exempt from at the time, as it was considered "women's work"). And even before dedicating himself to abolitionism, as a farmer, he was known for being on great terms with his indigenous neighbors, having a great deal of reverence and respect for them, their land, and their way of life.

In 1849, he and his family moved to North Alba, New York to live in the local black community. He still believed in a violent end to slavery but became more and more optimistic as he saw the growth and development of communities like his where free blacks could live their lives in peace, far from the indignity and inhumanity of slavery. This optimism was forever buried when, in 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was passed. While white abolitionists were talking of the gradual abolition of slavery, here was proof that their moderation was leading to nothing. Rather than be diminished, slavery as an institution was only strengthened. It was the imminent and very real threat of slave catchers invading these safe havens and dragging free blacks back into bondage that forced him to act.

"I have only a short time to live, only one death to die, and I will die fighting for this cause. There will be no peace in this land until slavery is done for."

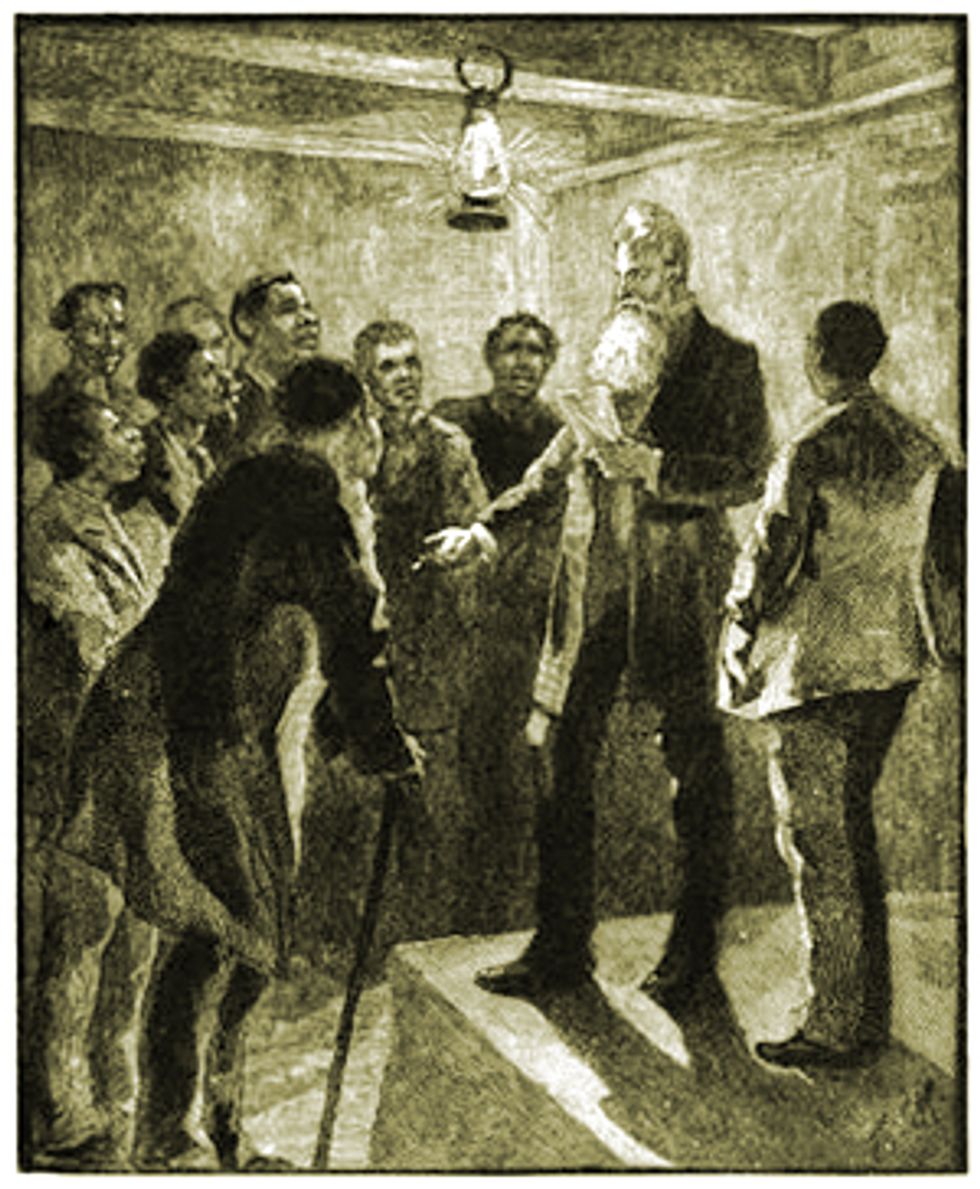

Brown returned to his old comrades at the Free Church in Springfield to organize the defense of escaped slaves. Together, they founded the League of Gileadites, an anti-slavery militia which was dedicated to defending freed and escaped slaves through force. They were an armed, illegal resistance group which did not go unnoticed by the federal government. This was simply the price of freedom. They did not expect peace and had every intention of fighting, even to the death. Another founding member, Reverend John Mars, told his congregation that "the time has come to beat plowshares into swords" for the defense of the rights and dignity of man.

Brown addressing the League of Gileadites | Photo: Nova Numismatics

The League was extraordinarily successful. Even after Brown left, not a single person in Springfield was ever captured again. William Wells Brown, an escaped slave turned novelist, would write of the city's unique defiance of the Fugitive Slave Act and of meeting armed blacks and whites patrolling the city's train stations, ready to fight any slave catcher who attempted to do business in the city.

Brown's revolutionary praxis would only get bolder and more violent from there. In 1854, amidst the chaos of Bleeding Kansas, he and his sons attacked and killed several slavers attempting to illegally vote to allow slavery in Kansas and who had murdered abolitionists months prior. There was also the famed 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry, a failed attempt to secure weapons from a federal armory to arm freed slaves with.

The fateful attack would cost him his life. Most of his band of twenty two were slaughtered as they surrendered. Among them were Brown's sons and numerous freed slaves. He and the survivors were arrested by none other than Robert E. Lee, then a colonel who led the retaking of Harpers Ferry.

Brown was executed by hanging on December 2, 1859. Though he had died, his revolutionary legacy would live on. He was immortalized in literature and art, having captured the imagination of militant abolitionists across the country. More importantly, his grime prophecy came true. Before the attack on Harpers Ferry, Brown had almost a thousand steel pikes forged to equip an army of freed slaves. These were confiscated by the federal government but ended up in the hands of a few wealthy and influential southern aristocrats who had these delivered to politicians and military leaders throughout the south. This was a warning. These steel pikes were what awaited them and their families if the southern states stayed a part of the increasingly anti-slavery Union. The message was clear. And at the Battle of Fort Sumter, the first battle of the Civil War, Confederate general P.G.T. Beauregard held one of these pikes in his hand as he ordered the assault on the fortress.

"John Brown" pikes on display | Photo: Bob Owen

Some have called Brown a terrorist and a madman. He is slandered just as mercilessly and as baselessly as all revolutionary heroes are. Reality paints a very different picture of the man. Brown was a skilled writer and orator. He spoke passionately about abolition, feminism, and egalitarianism and rewrote the Constitution to show how the United States should defend the oppressed and eradicate slavery and exploitation.

Now the real question is, what the hell is so crazy about fighting for your fellow man's freedom? What's crazy is a society which puts black bodies in chains. What's crazy are whites looking to compromise when black people are being killed and enslaved with impunity. Crazy is claiming to be anti-racist while systematically benefitting from racism and never once acknowledging it. Being outraged at oppression and taking a stand at the cost of your privilege is the most sane thing you can do. And it was as sane then as it is now, when black people are still being killed or dragged away, put in chains, and enslaved.

So as we remember John Brown and all who died in the ongoing struggle against racism and oppression, remember that while sane, rational moderates discussed the end of slavery, "madmen" were freeing slaves.