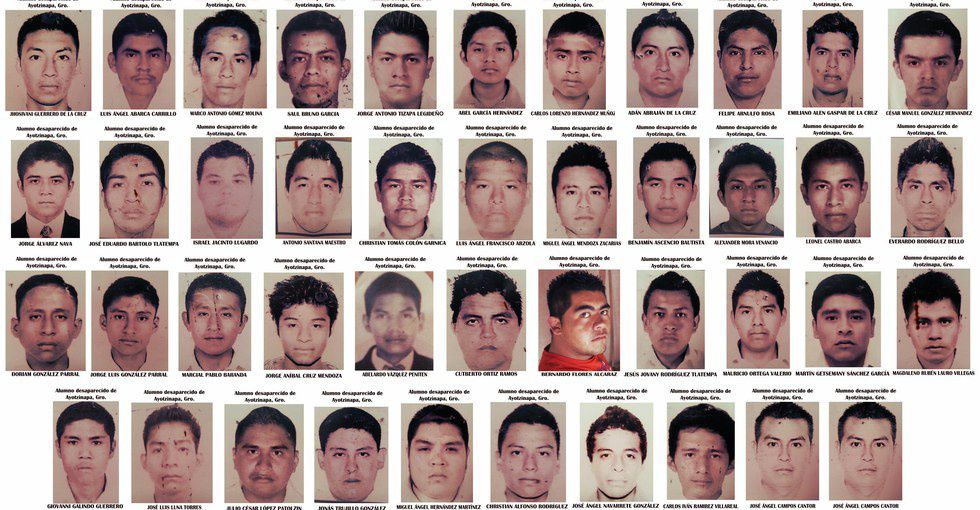

On September 26, 2014, 43 Mexican students from a teacher’s college in Tixtla, Guerrero went missing as they headed to Mexico City to commemorate the anniversary of the 1968 Tlatlelco Massacre. The students were headed to Iguala, ninety miles away, to pick up buses that would transport them to the capital but once they arrived at the outskirts of the city they were met with opposition from the municipal police force of Iguala that had been placed there to secure the city from any disruption by Iguala’s mayor Jose Luis Abarca Velazquez for his wife’s political event. As the student group attempted to obtain a bus for their journey to Mexico City they clashed with the police resulting in the death of six students, injury to twenty-seven others including bystanders, and the disappearance of 43 students.

The students were said to be in the custody of Mayor Abarca Velazquez who then handed them over to local narcos, Guerreros Unidos. In the investigation the following months, outside state actors like the United States, the European Union, and the Pope determined that instead of helping the students, the police force, federal troops, and government administration failed to protect their own citizens, covered up evidence of the attacks on September 26th and refused to provide any vital information to the parents and family members of the students.

In the last eight years, 180,000 Mexicans have been killed and another 30,000 have disappeared during the violence of Mexico’s war on drugs. The NarcoCulture that prevailed in South America in the 80s and 90s has moved north to Mexico bypassing the middle man to get to it’s No.1 customer, the United States.

Journalist Luis Hernandez Navarro compares in his piece, Ayotzinapa: el dolor y la esperanza, Mexico as an extended state of the United States that serves as its playground for illegal activity. The proximity to the United States, the vast levels of rural poverty, and the lawlessness that exist throughout the Mexican government (local and state levels) has made Mexico the perfect brewing ground for the “narcoestados” or narco-states, where politics and drug trafficking are intertwined.

In a statement by http://www.elcotidianoenlinea.com.mx/articulo.asp?id_articulo=3457, he explains the reasoning why the forty-three students disappeared:

The students of Ayotzinapa were young, the majority of them being sons of peasants, students of a Normal Rural school. For that reason, the disappeared in the forced fashion that they did and they were murdered. They defended public education, rural nominalism, teaching the communities without access to education, and the social transformation of the country. That is why they were kidnapped and executed.

From its creation, the left-leaning Rural Normal Schools and the Teachers College in the farther corners of Mexico were met with opposition from the right elitist who’ve sought to trademark the peasant’s quest for social equality as communism. Education for the poor, indigenous, or peasant class of Mexico has never been in the interest of the government who’s placed more attention towards achieving a western capitalism system than citizens’ rights. Socialism, equality, and education are all enemies of narcoculture, especially in the towns’ dependent drug manufacturing and trafficking. The students from the Rural School of Ayotzinapa were the ideal targets for a politically corrupt city like Iguala and the state of Guerrero, which was and still is very intertwined with organized crime syndicates.

So how do two separate student incidents with the government 46 years apart relate?

The 60s and 70s in Mexican saw the peasant/working class, some of them educated at the Rural Normal school and Teachers College, protesting social rights and leading civic movements around the state of Guerrero. At that same time, the middle/upper-class student population of Mexico was becoming heavily influenced by western culture of ‘1968 the French (their protesting nature and cinema) and Americans (their fashion and music). More liberal than their parents before them, the Mexican youth of ’68 believed they were waging revolution alongside the impoverished Mexicans from rural areas, but these college students failed to realize that they’re economic backgrounds created a divide between themselves and the working class.

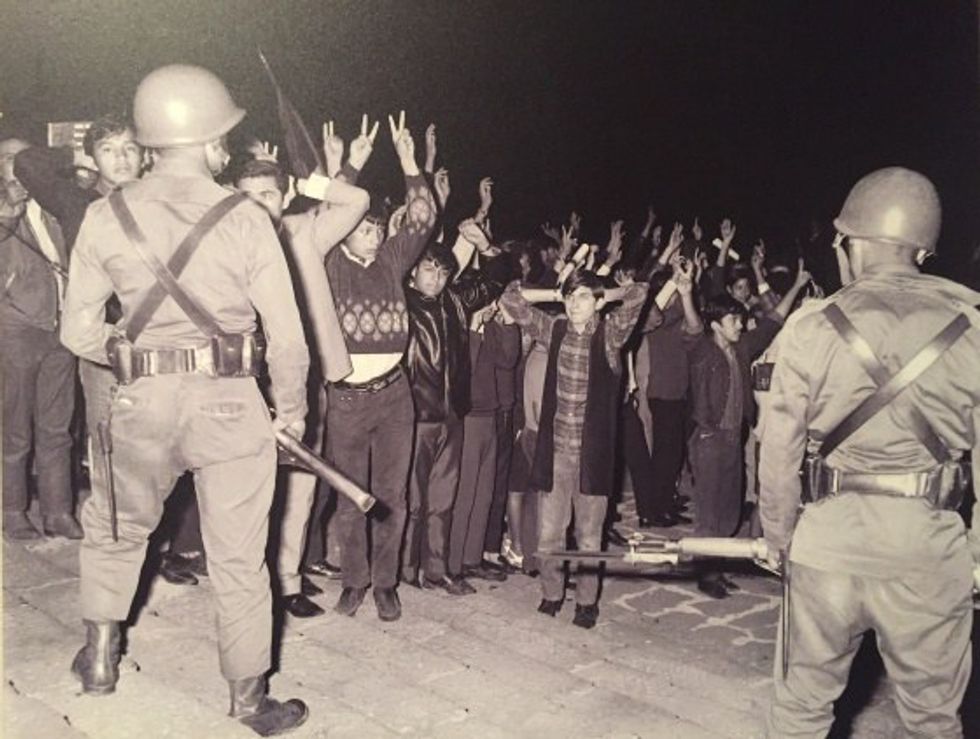

In July 1968, students in Mexico City were celebrating Fidel Castro’s first uprising and protesting the illegal incarceration and abuse of power on behalf of the Mexican police force. The events in July would spark a summer of irritability and unrest for then Mexican president, Gustavo Diaz Ordaz, who was preparing Mexico City for the Olympic Games in October. Fearing an international student protest like the ones popping up all around the globe and obsessed with the events that unfolded during May in Paris, “Diaz Ordaz [would] decided to play Charles de Gaulle” and use violence as a means to end the student up roar in Mexico City.

By August and September, the student unrest cankered like a sore on Diaz Ordaz when he decided to occupy the National University and eventually with the aid of the secretary of interior, Luis Echeverria, orchestrated what would become known as the Tlatelolco massacre.

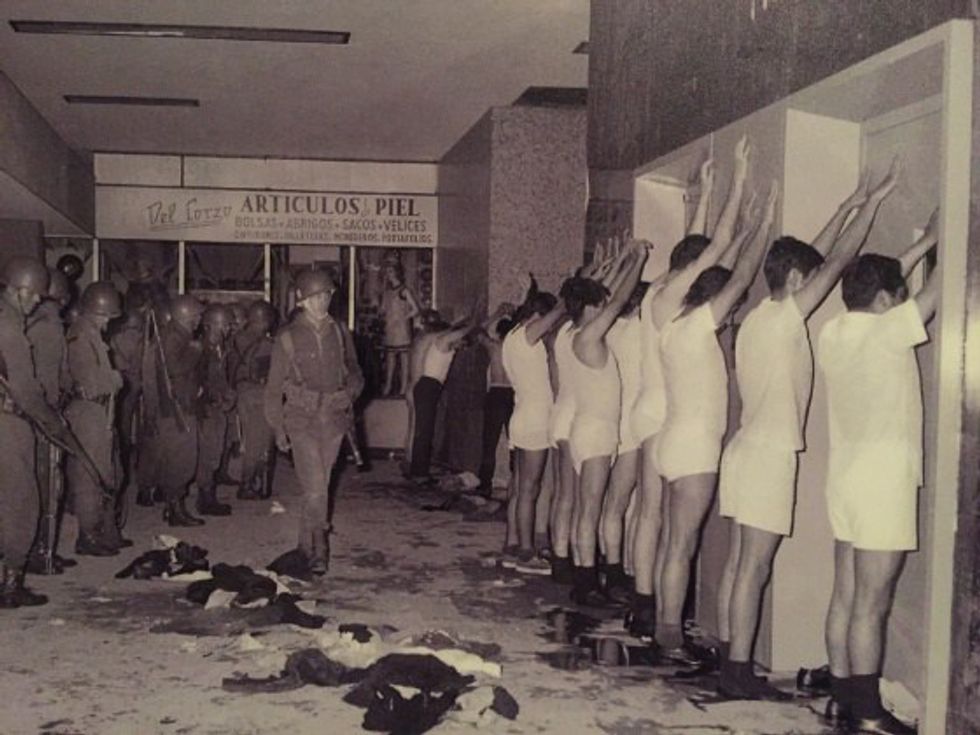

The actions of October 2nd 1968 by the government of Diaz Ordaz at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas arose public displeasure from all corners of the world watching as Mexico prepared to take on the Olympics. Figures range from 30 to 300 to the thousands, but it was obvious that dozens were killed by the use of federal and police forces. The tourists and families at the plaza that day were the witness in this massacre and the media would twist the events to paint the government as a mediator not an agitator.

In 2014, the students who lived to tell of the violence at Iguala were the witnesses and the seedy government of current Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto and the intertwined narco-politics of the state of Guerrero are the culprits who have yet to be prosecuted.

From Tlatelolco to Ayotzinapa, the pursuit of justice must come to Mexico to ease the pain of the families still looking for answers, fifty years later. Two years later, a police chief has been arrested in connection with the missing students yet no government official has come forward to explain to the families or take responsibility for the events that unfolded in September. While the government has brought to light some of the documents from the massacre of 1968, the country’s political ties to drug trafficking in the twenty-first century are only a replacement for the corrupt authoritarian government that once ruled.