Spin the wheels of memory back to your first poetry unit in high school. Perhaps the cold and bleak English room, dotted with semi-inspirational quotes and bad posters, made you wonder how far you could get in life without a diploma – or maybe the phrase "five paragraph essay" brought you some sort of inhuman joy.

Try to recall how your eyes closed and begged you to sleep for just a few minutes when your bird-like teacher began rattling off “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost, and chirped to a small crowd of unmoving hands, somehow just as tired as you, over what it means.

Reminisce on the way your empty stomach burdened you with gut-wrenching excitement once the bell rung an unnecessary number of times, cutting into the shrill announcement that “over the next few weeks, we’ll be deciphering certain works of poetry, and tomorrow we’ll discuss the difference between prose and...” Remember how quickly you shut your books and stumbled out into the warm humdrum of walking the halls?

Now revisit the unit three days in. One of the posters was hanging by a single piece of tape, and it was either freezing or burning. God knows your English class was never temperate. “Today we’ll be discussing William Carlos Williams.” You were handed another piece of colored paper which read:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

and asked yourself, what the f**k is this?

I’d like to tell you.

In our society, we’ve got a vague sense that poetry is good for our souls, makes us sensitive and wiser. Yet we don’t always really know how this should work. The stuff has a hard time finding its way into our lives in any practical sense – so unless you deliberately enjoy the stuff, it was probably only force-fed to you in that godforsaken classroom.

You might’ve brushed over this topic in that room, but there’s no doubt you were asked to write at least one.

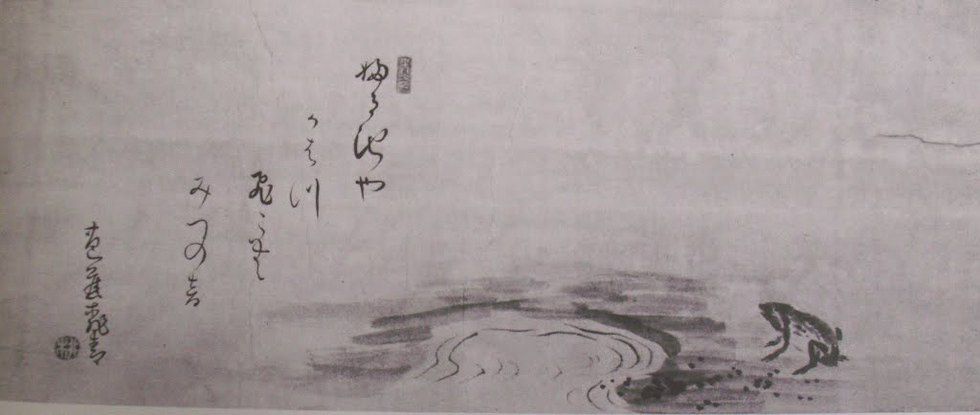

Old pond…

A frog leaps in

Water’s sound

A haiku, by Matsuo Basho. Considered the greatest master of the craft, he believed that poetry was a medium which ought to bring us wisdom and calm, as defined in Zen Buddhist philosophy.

Matsuo Basho white-knuckled the cultural aesthetic of Wabi-sabi, a Japanese worldview centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. Each haiku he wrote was done so with the intention to remind readers that what really matters is to appreciate the moment we’re in, to be attuned to the very simplest things life has to offer.

Imagine a drive down the wooded portions of route 97 in the light of autumn, just as the leaves begin to change color or the laughter of your closest friend. Imagine the illuminate glow of a firefly on a cool summer night. These instances, when truly appreciated, allow us to feel a brief sensation of merging with the natural world; regardless of how much we groom ourselves to stand out, we are a part of nature.

Basho insisted that the purpose of haiku, is to capture these moments, to remind us of them, and help us invoke the contemplative calm which we feel in their midst.

Think back to the name which caused you so much pain, William Carlos Williams. His initials a popular Wednesday hashtag, and his curious identity a wonderful jest to the "two first names" bit brought up in “Talladega Nights: the Ballad of Ricky Bobby”

When Williams wrote that ridiculous piece of uninterpretable agony, he did so on a tiny prescription pad on a rainy day, like the one in which you read his poem for the first time. The patter against your classroom’s windows, had you listened to it for just a moment, may have brought you terrible melancholy, and the overwhelming desire to up and leave school.

Williams was looking through a gray-stained window, into the dreary world outside, and jotted down what he saw in a way that would allow him to feel how he felt in that simple moment again. A motive similar to that of Basho's.

The audacity of your English teacher, was the firm-held belief that every poem ought to have some complex undertone, a hard-found analysis, some political message or drama; when instead, the message in this case is simply whatever you feel.

Compare the works of Basho to the poem by Williams, and you may see the truly simple and haiku-esque intentions of "The Red Wheelbarrow."