As a new member of the Christian faith, there are certain values related to its spirituality that I loved and would have preached to myself even if I was atheist. I value logical explanations to worldly phenomena much less than I used to, because I do not believe everything can be explained logically. Many things in life don't make sense; that's just the way it is. I still believe in evolution. I still have questions over many of the events in Genesis and whether they happened.

However, those questions are not that important to me, and have taken a backburner to the values that have become especially important to me. Vulnerability, grace, hope, love, peace, and justice are among those values, which I have written extensively about in many articles.

But one part of the Christian faith, and many religious faiths that has been on my mind lately is surrendering. A fundamental part of religion and spirituality is that you are not in control of your life; a higher power is in control. You don't have all the answers, and maybe you never will. In spiritualism and faith, you find love, freedom, and happiness not through trying to control everything. You find those things by surrendering.

I initially intended to write this article about the role of spiritualism and religion in recovery. Whether it is from a trauma, addiction, or tragedy, spiritual faith seems to play a role when circumstances make absolutely no sense, in times when the world seems so evil that a loving God does not to exist.

In writing this article, I think no further than Alissa Parker, the mother of Emilie Parker, a 6-year-old victim in the Sandy Hook Massacre. She wrote a book title An Unseen Angel, a story of her faith-filled, spiritual path to coping and healing from the death of Emilie. The book is not about the event and massacre in itself. "I prefer not to look at it that way. Although it contains tragedy, my story is ultimately not tragic...It is a story of how God's love and protection surrounded me during my darkest hour." Alissa Parker goes on to note that her daughter's life was not one of despair, and her hope in sharing her story of faith and spiritualism following her daughter's death is so "others who find themselves in dark places can discover the unseen angels in their lives helping them turn to the light."

I'm reminded of Dr. Viktor Frankl, an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor who wrote Man's Search For Meaning. In one part of his famous book, Frankl explores the question of transcendent experiences amidst extreme suffering, and uses an anecdote from his own time in a concentration camp, wondering whether his wife was still alive. In this moment, he saw what he describes as a truth known to many poets, and a "final wisdom." That truth was that "love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire." In the moment, Frankl has a conversation with an image of his beloved wife: "I asked her questions, and she answered; she questioned me in return, and I answered."

Although he still had a conversation with the image of his wife, he still didn't know whether she was alive. What he did know, in that moment, was that "love goes very far beyond the physical person of the beloved." It isn't important whether the physical person is actually present; the spiritual being of the person, their inner self, is much more important. "I did not know whether my wife was alive, and I had no means of finding out...but at that moment it ceased to matter."

Later, Frankl argues that despite circumstance, people can be free in spirit, that we are not wholly defined by our environments and circumstances. "Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress." He references men in the concentration camps who comforted others and gave away the last of their bread, even when they were about to die. Even though circumstances such as extreme sleep deprivation and extreme hunger and thirst afflicted many prisoners, in the final analysis "the prisoner was the result of an inner decision, and not the result of camp influences alone." Spiritually and mentally, we are free. We always have choices, and in the words of Frankl, reminded by the martyrs in the camps, "the last inner freedom cannot be lost...the way they bore their suffering was a genuine inner achievement. It is this spiritual freedom - which cannot be taken away - that makes life meaningful and purposeful."

By surrendering to spiritual higher powers, it's clear, to Frankl, that the way we handle our sufferings, the way in which we "take up our cross," are the ways we add deep meaning to our lives. And these situations and martyrs of very high moral character are not found in only concentration camps; "everywhere man is confronted with fate, with the chance of achieving something through his own suffering." Frankl once knew a boy in a hospital who had an incurable illness. He would not live very long. He wrote to Frankl of a film he'd seen in which a man waited for death in a courageous and dignified way, and this was the boy's chance, too, to confront death in a similar matter. "Now...fate was offering him a similar chance."

What strikes out to me in the stories of Alissa Parker, Victor Frankl, and the boy in the hospital is this indescribably deep joy, much more so than I have achieved. Paradoxically, they seem to have so much control over their freedom, despite having surrendered to their spiritual lives. There are many ways to find joy after and even amidst tragedy, and religion and spiritualism are not the only ones. Many people find joy through political action and making sure actions so horrific can never happen again.

But I don't believe the world and its circumstances make much sense, even when they seem to. Some things are unexplainable, and my conversion to Christianity was in part a means of being at peace with those unexplainable things. So many parts in the Bible don't make much logical sense, and yet I, too, want to surrender to God. There's a lot going on in my life, a whole lot of pain, that I, one day, want to be worthy of having suffered.

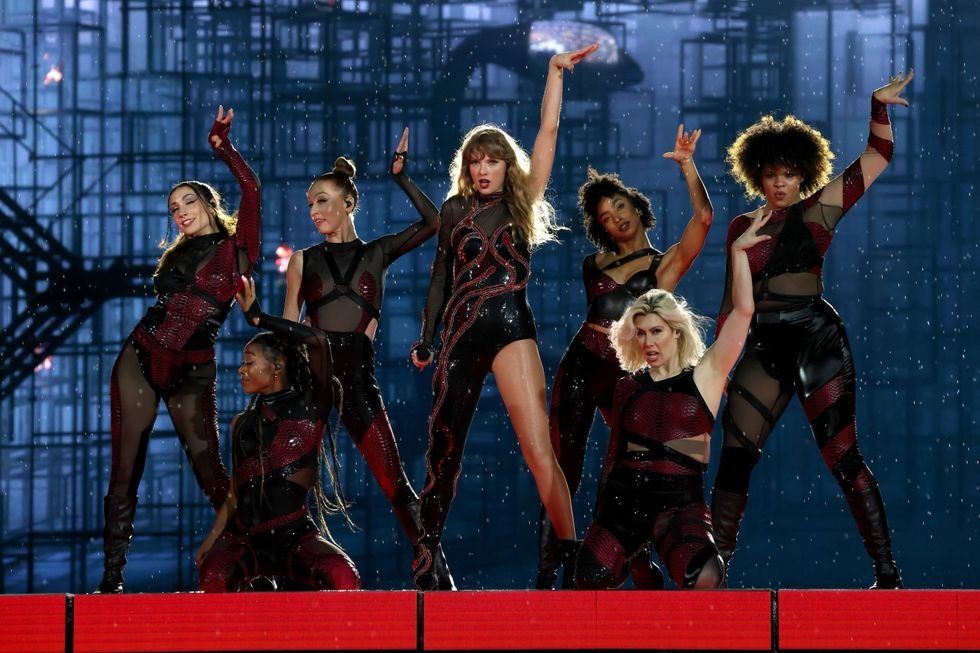

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.