For such an historically resilient and beautifully designed space, the Commons are pretty wild.

When I first moved to Boston from Maryland, the very first place I visited outside of my campus was the Boston Commons. Allured by the sense of adventure and exploration, my first MBTA ride shot me past the MFA, Symphony, the Prudential, Copley Square, and settled in the heat of late August in a stirring station. Perhaps mindlessly, I scaled the stairs of Park St. and emerged into the heart of Boston: the Commons.

Commons are, by disposition, areas of shared space within the city. Decorated with trees on grassy fields and identified by large open spaces, the commons are beautifully designed. On my first visit, I remember seeing legions of dogs, picnics along the pond, and soccer balls launching across the green. The Boston commons are especially beautiful with specifically planted flowers and a variety of trees that arc over the laden pathways. It's almost surreal.

That is until you hear the chanting.

On my first day at the Commons, the late Billy Graham's son, Franklin Graham, was on his, "Decision America," tour and he had a group of about 200 to 300 people standing, sitting, and cheering on the ground. During the entire challenge, there were counter-protestors carrying signs throughout the crowd, challenging the people who had gathered. After coming from small-town Maryland, I was taken completely off guard.

Protest of the Syria War on the Boston Commons - March 17, 2018

Now,

what makes the Commons complex is the very thing that makes the commons

so beautiful: it's accessible to all members of the community. By that

liberty, it is not uncommon to hear protests, political meetings and

rallies being held in and around the commons, often in front of the

State House. The commons allow a space for ideas and policies to

converge and unite, unobstructed by property owners or government

officials. The commons foster the First Amendment right and they have

reoccurred in urban planning time and time again.

But the constitution of the commons has been under fire throughout history, Sometimes directly like the Kett's Rebellion where the wealthy put up fences around the commons and a rebellion tore the fences down. Sometimes indirectly like the redesign of Tompkins Square Park in 1992 that severely limited the open space of the park with tall black fences. Making the commons not only accessible but also riot-proof has been a balance that has become only more apparent in the wake of political tensions and movement marches.

And yet, I'm not certain we realize

why the commons are as important as they seem. What makes a patch of

green surrounded by shops, cars, and frankly too many birds the grounds

of revolt but also amalgamation of a diverse community of people. How do

cities found without delegated common space respond and gather to show

their voice? What is the future of the common space?

Perhaps the answer rests along the side of the highway.

My name is Michael Bair and this is, "The Reformist".

RESEARCH

What is common land? Simply and by the dictionary, it's a space owned by no particular person and instead is used by multiple people. It's a non-programmable space by definition but that hasn't stopped the government from adding particular venues in certain places like public art, fountains, ponds, statues and so forth. The commons are both a celebration of unity and a space for thinking. A particularly effective commons has a multitude of open spaces that allow for a variety of activities and people to come and go as they please.

Muscian on the Boston Commons (Photo courtesy of @humans.of.boston)

But

as previously mentioned, city planning has tried to stiffle the

openness of the commons in the past. Most apparently is the redesign of

Tompkins Square Park in Manhatten, NY. Take the immigrants protesting

unemployment, the infamous Tompkins Square Riot, or the protests of the

Vietnam War. To defer and disinegrate these gatherings, Tompkins Square

Park has large black fences bordering every green space, effectively

dividing the space into thinner and less malleable paths. The balance of

freedom and control is complex and requires thought on how to better

the land.

To determine how to improve the commons, we must recognize why the Commons work. Commons allow for large groups to gather and demonstrate their voice. Nearly every city have protests but the direct correlation seems that with easy access to a designated common, the protests are peaceful and allowed to filter before elevating to violence.

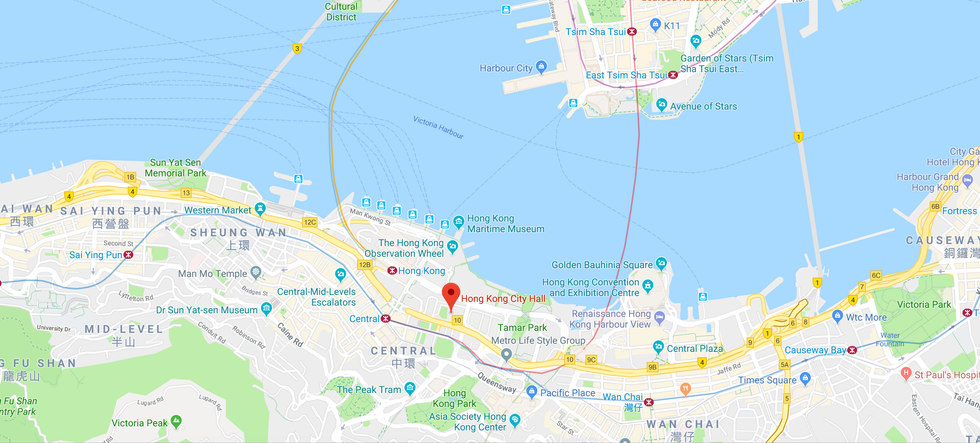

Unfortunately, not every

city has a designated common and this increases the number of protests

in a city. We can look at this through the distribution of protests in

cities internationally. Looking by sheer numbers, Hong Kong comes in as

the city with the most protests. Although research is thin on the exact

numbers, according to The Guardian, police reported that,

"As

the city state struggles to maintain its autonomy from Beijing,

authorities recorded 11,854 public assemblies and 1,304 public

processions in 2016."

Hong Kong, China

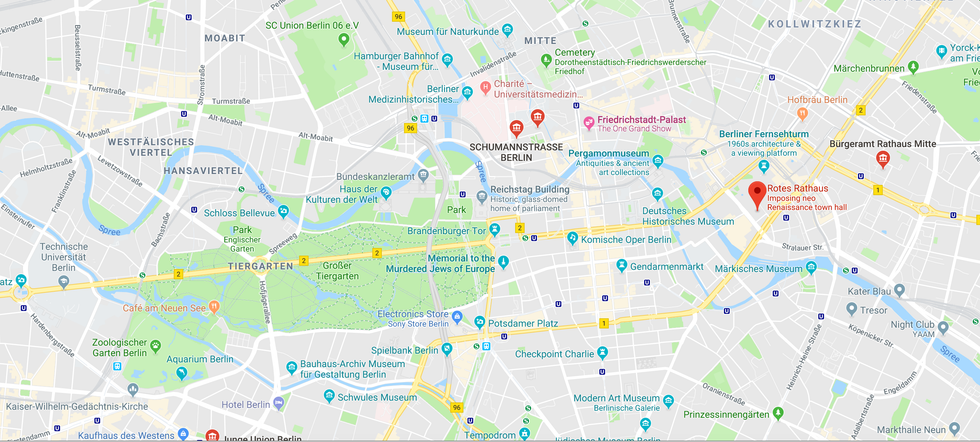

Berlin, Germany

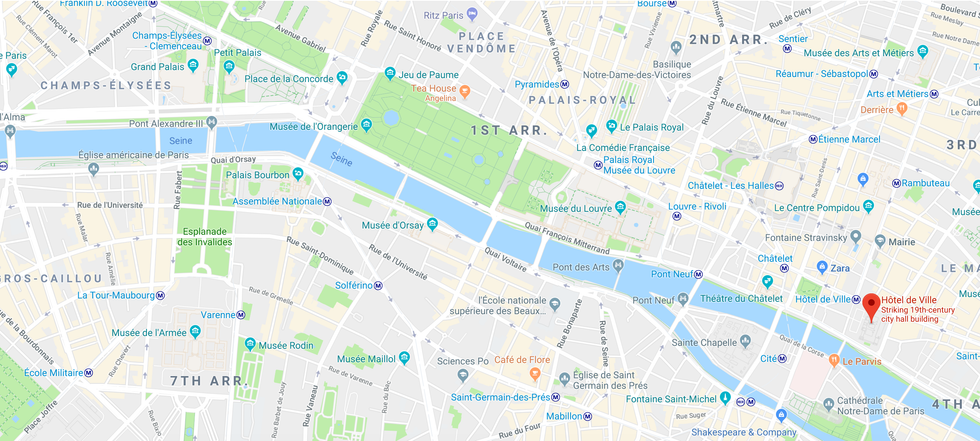

Paris, France

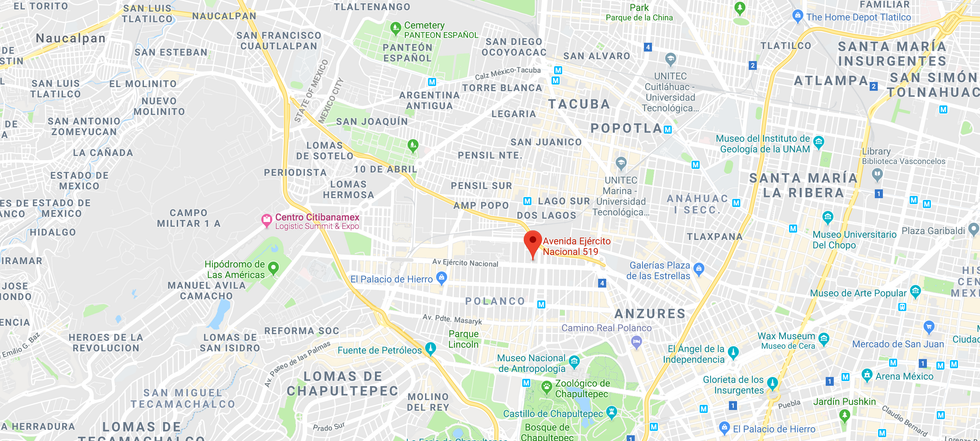

Mexico City, Mexico

City

Halls and State Buildings are categorized by certain architectural

features even internationally. They are monumental and symbolic,

emphasizing power and standing as a single entity of the governing body.

In Berlin, the city hall Rotes Rathaus

has a complete spire akin to the cathedrals of the Gothic era while the

city hall of Paris has a multitude of statues and molding of intricate

detail. They are symbolic of the distribution of wealth where the

architecture stands as a statement and opposition to rally against. By

removing these symbols from any perceivable common, the common lacks

it's figure.

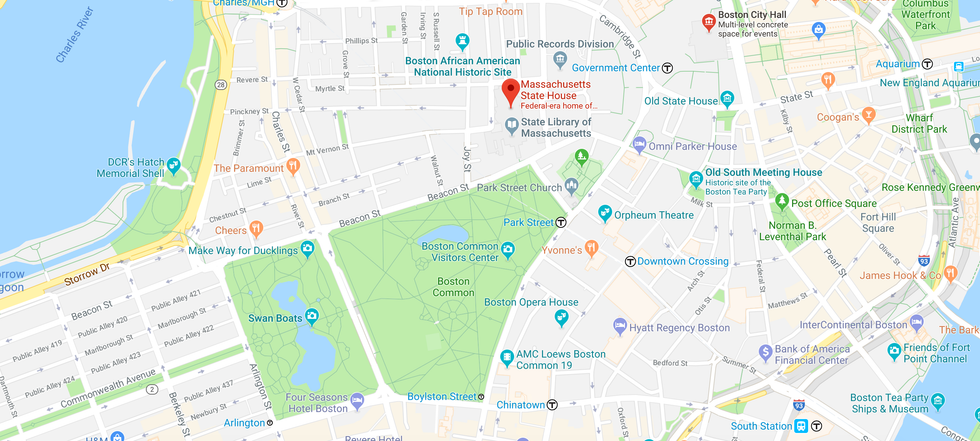

Once again returning to Boston:

Boston, MA

The Massachusetts State House is located AGAINST the commons, looming over the Park St. T station and the Park Street church. Even Boston City Hall is nearby with it's own large concrete common around it. The Boston Common is positioned in a way to be surrounded by the architecture on all sides. The capitalistic skyscrapers clashing with apartments and historical monumental creates a merging and mixing atmosphere that permeates the commons with the backdrop for revolution.

By not providing access to not only a large common space in direct context to the state house, the cities of Hong Kong, Berlin, Mexico City, and Paris all refuse the narrative urban structure and fail to establish the identity that the Boston Commons does well.

But the reason dates

back to the history of these cities. Although Boston was established

under British rule, the commons were a byproduct of the English urban

planning with London also having a sort of commons around the city hall.

Paris was originally conquered by the Romans, Berlin faced drastic

political turmoil like the Thirty Years War and of course the Berlin

Wall, Mexico City was originally Tenochtitlan until destroyed and

redesigned by the Spanish, and Hong Kong faced intense urbanization to

the point that the quality public spaces have only been addressed

recently.

So how do you combat the lack of space in a city of spaces.

You move between the spaces.

There's a wonderful book called "The City & the City" by China Miéville describing through a film noir the spatial relationship of two cities called Besźel and Ul Qoma.

Drenched in political statements, the story implies a setting of a

single city while telling the reader it is two twin cities under the

volition of the people. Therefore, each city must not perceive the presence of

the twin city, dare face the consequences of not adhering to the rules

of the powers above. The only moments of perception and true clarity are

in the in between segments of the cities...the thresholds so to speak.

In a way, perhaps redefining the common space through a recognition of thresholds is the key. If finding the connection to the body of government through a different sort of common, perhaps the same effect can be reached. Looking at city planning, there's a variety of landscaping elements that could fit the description of a quality space.

Small patch of open space in front of the Hong Kong City Hall

But the problem is: what do we name this?

It

may seem inconsequential that spaces like the one in Hong Kong above

have no specific name. But how do we define a space, we give it a name.

By giving something a name, you can create a discussion about it, you

can make it the subject of tests, innovations, a meeting spot, or even a

space for change.

Graham Coreil-Allen from my home of Baltimore, MD spoke on the subject with Roman Mars of 99% Invisible. In the podcast, Graham says,

"By

giving these places succinct, and fun, and poetic names, we can help

start a discourse about our public spaces and how we envision them for

the future"

CHECK OUT GRAHAM'S NEW PUBLIC SPACES HERE: http://newpublicsites.org/

What Graham does is he takes particular spaces like the green between the highway or a lone tree along the sidewalk and gives them each unique names. That patch of green between the highway isn't just any patch of green...it's a Cosmopolitan Urban Meadow. That lone tree isn't just any arbor, it's a Sanctuary Tree. What Graham does is empower these spaces by giving the tool of language to those who can impact the site. If you cannot speak about a place, how can you attempt to achieve anything.

So going back to the small patch of green in front of the City Hall in Hong Kong, we can begin to assess its qualities. It's shape is irregular, leading to the idea that it was an afterthought. The grass is well kept despite it's small area, leading to the assumption that the government still takes notice of this site. Lastly, we can notice larger structures and access points around the plot, leading to the idea that it's dynamic with multiple elevations and access points.

Taking this all into account, let's name it... a Spontaneous Habitual Lawn

Terrible

name aside, by naming this space, it can become part of the discussion

and the planning. People can gather at the spontaneous habitual lawn by

the city hall and have a strike, they can have a picnic, or they could

simply meet a friend.

And

this happens already to an extent, even in Boston. On my commute to

work, I walk by a patch of green at the intersection of two major

streets. It's a considerable distance from the commons but has an

overwhelming minority population and lower-income housing. With the

economy, this area is seeing major construction and their common spaces

are being overtaken by construction vehicles. In response, there was a

group on this patch of green protesting for construction worker's

rights. It was a moment of guerrilla space-making but a byproduct of

unsatisfied quality public space.

Cranshaw Construction workers protesting on the unnamed commons in Roxbury

By integrating these between spaces happen to be prevalent all over the world because they aren't always designed but are birthed from mistakes or a lack of resources. Even when the urban planning does not account for the traditional common grounds of Boston or Baltimore, the responsibility rests on the citizens to discover their own place-making. The framed void of public spaces allows for those without a ground for a voice find that place. The future of the commons may not always be created but rather, they may be named.

REFORMED

Designing

landscape is a particularly challenging problem. Working with natural

resources means a sense of respect and gentleness that is unprecedented

with building offices. But design of the common space doesn't require

much. Instead, we as citizens bring the power behind the commons and

nothing examples that better than the New Public Space

movement. In redefining what is a public space or common land, the

identity of the common is irrepressible and able to persist beyond urban

planning.

What is the future of the commons? The Boston

Commons model will remain but for cities with unprecedented public

spaces, the setting for gatherings and protests are more malleable

and versatile. Perhaps by taking ownership of these forgotten voids in

the city, the voice of the citizens can never be suppressed. Resist

those who say architecture can solve all of the cities problems because

the commons are where design meets the user where it is not defined by

the technique by made out of it. The commons aren't a space, it's what

we bring to it.

It's time to take back the commons, wherever we may find them.