I've had the wonderful blessing to travel in my childhood. After a brief brush with a heart attack, my father decided late in my childhood that he would no longer leave his ambitions for a better day, but rather take chances as they came. That's how I found myself in a crimson van across the continental United States my junior year of high school. In our odyssey from coast to coast, the unrequited beauty of the landscapes was only matched, in my opinion, by the cities we passed through. I found views of Chicago at night or San Francisco's rolling urban sprawl to be particularly breathtaking moments in our journeys.

And I'm not alone in this judgement because Alain de Botton of the education-alternative group School of Life presents the attractiveness of cities as, "objective". He breaks down why we find cities attractive and more importantly what we look for in cities. It's a great listen and worth your time.

SEE THE SCHOOL OF LIFE ON ATTRACTIVE CITIES FOR YOURSELF:

Alain de Botton's first fundamental rule is order and variety. Cities must have a sense of control but also a series of unique movements out of these pentameters. But the conflict of order and variety often manifests itself in the nature of graffiti.

Graffiti is defined in the Oxford Dictionary as, "writing or drawings scribbled, scratched, or sprayed illicitly on a wall or other surface in a public place". It can as insignificant as a name on a single brick or as immense as the "THIS LAND WAS OUR LAND," illegal marking in California's Mojave Desert in 2015.

THIS LAND WAS OUR LAND - 2015, Photo courtesy of VICE

What makes graffiti unique is ironically it's predictability. Every town hosts its own family of types and styles. From my time traveling, I have always been interested in these messages with no discernible source. That's because, unlike most art, graffiti is done in secret due to its illegal connotation. Although I do not condone vandalism, this nature makes for a regimenting voice and culture that permeates through the noise. Whether in New Orleans, Austin, Boston, or California, graffiti has long been a statement that requires a permanent host because the source cannot linger in fear of authoritarian intervention. Who or what will the host?

The perfect cohort hides in our architecture. But more importantly, what does graffiti say about architecture and how can this relationship reveal an unseen identity of our cities?

My name is Michael Bair and this is "the Reformist".

RESEARCH

Graffiti in Austin, TX

We engage this type of artwork almost by chance. Just as we don't plan on unincorporated towns off of the highway, we don't intentionally go searching for graffiti, we find ourselves with it. In searching for graffiti around Boston, I visited the typical places. I visited the MBTA stations, I looked around public alleys, and scoured the empty parking lots. I even looked for it on my lunch breaks in Roxbury. I came across the usual figures: gang tags and illegible markings seemed almost unbearable.

But it wasn't until I stopped visiting these admittedly stereotypical spaces that I began to fixate past the admissible. I visited North Station one night and walked around the adjacent area. Mesmerized by the almost psychedelic energy of the downtown atmosphere, I began to acknowledge something, or rather the lack of something. The infrastructure almost seemed lively and open, not laden with equipment and urban permanence. It seemed to almost lack the nature of sidewalks, instead melting into a gathering space for long friends and lovers.

Fascinated, I nearly fell head over heels on a large box before me. Wincing, I turned to come to face with a simple electrical transformer. But oddly, this transformer wasn't saturated in the torpid grayish-green that usually found residence in mundane equipment. Instead, it was painted like a basketball. In fact, nearly all the transformers were decorated in layers of art.

Electrical Transformers near North Station, Boston, MA.

"But this isn't graffiti, this is public art," I thought to myself. There's distinction between the two I thought. But I recalled by previous "Reformist" piece on the commons (LINK:https://www.theodysseyonline.com/reforming-the-com...). There's no power in a movement or space without a name and the word graffiti has long-held stigma, rightfully under its status as destruction of property. And yet, the line between graffiti and public art becomes so fine in this case. Although surely done with permission, the transformative nature of the art on the transformers got me thinking.

What does graffiti mean to architecture?

Think of all the locations I had previously noted: subway stations, public alleys, empty parking lots, empty brick walls. These spaces hold various programs and yet hold a homogeneous fate: they are often left to disrepair. Subway stations often are home to a copious amount of trash, dripping ceilings, and the occasional subway rat. public alleys by their small and forgotten nature means it's left to disarray in storms that cause damage to the spaces. Empty Parking lots are a reminder of the effect of automobiles, often with oil spills, like-minded trash collections, and destroyed environment. These spaces don't only have disrepair, they embody them.

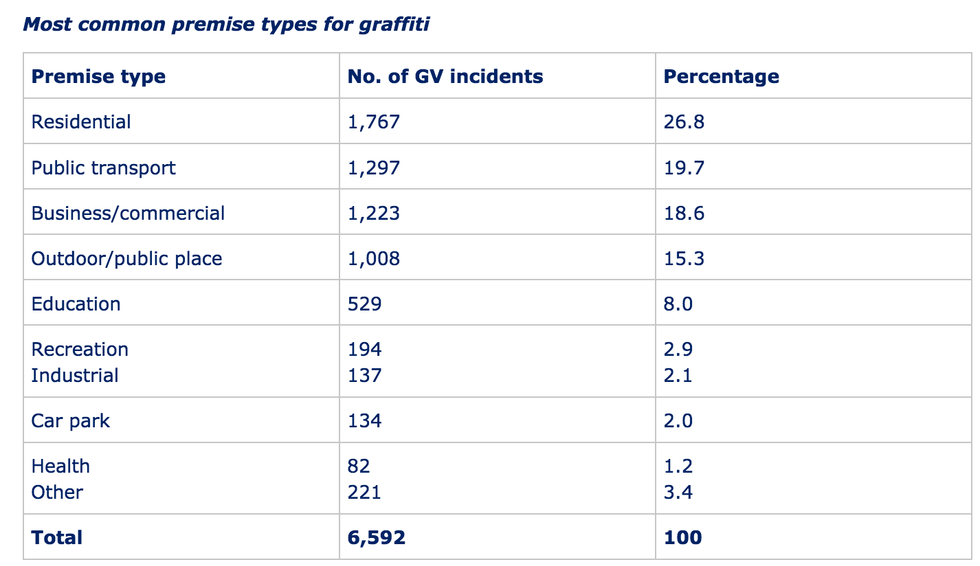

Australian graffiti statistics provided by the Government of New South Wales

Likewise, the blank brick wall is almost infamous for its role in vandalism. Walls by nature define a beginning, an end, or a change. When we encounter a wall, we must either stop, go around it, go above it, or go beneath it. Walls require decisions and movement.

But why graffiti in these spaces? What does marking these spaces do that, otherwise, the architecture cannot achieve? Often these vandals do have political statements but why position these statements on these specific architectural spaces?

I propose graffiti is a cultural response to the failure of architecture. As a humanist, I value human-centered design as I figure everyone deserves dignity from design. In these previously labeled space, the architecture does not fulfill was it intended to do. Subway stations are hubs to connect parts of a city together. Public alleys are spaces for residents to have control in a large city. Parking lots are spaces to gather and bring together. Walls are meant to protect or defend. Architecture has a meaning behind it.

If these spaces don't impact the community in a positive way, graffiti is the marking of politics but also the failure of the architecture.

Graffiti on a commercial building in Roxbury

Graffiti marks a design element with something crude and perhaps loathsome as rejecting this reality. If architecture designs how we interact with the world, how can we hold ourselves accountable unless the voice of people are heard. Graffiti can be the voice of rebellion.

Given credence to graffiti as the voice of people is that it has no sole perpetrator. The Australian Institute of Criminology notes in their own words:

"Preliminary graffiti research data from WA Police Force indicates the

main offending age is between 12 to 25 years old from all socio-economic

environments. The largest percentage of offenders are from mid to

high-level income families with a median age of 15. This is supported by

both national and international research."

FULL SOURCE: https://www.goodbyegraffiti.wa.gov.au/Schools/Fact...

Even the all-too-familiar phallic graffiti can find some meaning. As Galen Smith of the book, "New York Dick" says in an interview with Roman Mars of the wonderful podcast, 99% Invisible:

"In this space, in this context, you really can make your own counter-argument, your own counter-statement...and everybody knows what you mean".

In what many if not all would say is even a bit stupid, the priapic symbol is the plainest and simplest form of disrespect. It's not high art but it remains are voice of idiocy that most people live through.

So what can we as architects and designers learn from these voices?

In Cambridge, MA, there's a small example in asphalt we call, "Graffiti Alley".

Although also titled, "Modica Way," the colloquially named Graffiti Alley has a simple purpose. It acts as a connection between Mass. Ave and one of the dozen public parking lots in the city. But it's that in-between space that fosters the community together.

Graffiti Alley, Cambridge, MA

Adorn by simple skylights, the alley is colorful, vibrant, nearly chaotic in design, and easy to miss. The plan brick walls of the adjacent buildings define the space with light pouring into the alley from above, there's little to dissuade an artist from adding his or her work to the alley. It takes full advantage of the short-lived lifespan of street art and cycles on a weekly basis nearly from professionals to amateurs. It's a space for the user's creativity to fester into product and ideas to be put onto stone.

What Graffiti Alley does right is it shows the value of user input in design. If these marks are placed on examples of architectural shortcomings, the Graffiti Alley shows that given the opportunity to voice their concerns, the populace is eager and, in fact, irreplaceable in architectural design. If architects can muster the kind of community input like the Graffiti Alley in Cambridge has, then the diverse ideas of the individuals can only result in more creative and better architecture for the entire community.

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT GRAFFITI ALLEY, CHECK OUT THEIR FACEBOOK: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Graffiti-Alley/4877...

REFORMED

At the moment, graffiti is still considered vandalism and is illegal. Therefore, I cannot condone its practice and instead would like you to consider what graffiti is as a movement. Graffiti as a marker of the failure of both people and architecture. Graffiti as a voice to those without a mouth. Graffiti as an expression of creativity and an eagerness to be involved in the creative process.

But what graffiti means in the modern context is, as always, up to the community. Cities spend money and time fixing and removing these markings from the streets and on both sides, there are costs. It's not a simple conflict and I hope to not present it as such.

Graffiti in New Orleans, LA

Graffiti shows a desire for people to impact their built environment. From the low to high-class, the need for voice in design in prominent and vandalism is the precedent for said voices. The future of design means that instead of vandalizing the urban environment, our communities will build them.

But as we travel our nation and internationally, take intentional care to lose focus in a sense and peer beyond the skyscrapers and around the fountains to the corners of our cities.

Whether on the east coast or west, north or south, find the voices, give them attention, and notice the people making their mark on our built world.